A new archaeological research project at the University will reconstruct urban life in cities such as Constantinople during a period of history that has long remained hidden from view.

Reconstructions of daily life in ancient Roman cities such as Pompeii are plentiful, thanks to centuries of archaeological research. But that is not the case for the later Roman or ‘late antique’ period (AD 300-650) that saw the long transition from the Roman Empire to the Middle Ages.

This is set to change , thanks to three-year project that will see the University’s Dr Luke Lavan, a lecturer in archaeology, leading a team studying artwork, excavated artefacts and the ruins of ancient cities from around the Mediterranean. The project, ‘Visualising the Late Antique City’, is being funded by a £180k Research Project Grant from the Leverhulme Trust. Although Constantinople is now obscured by modern development within what is now Istanbul, other sites in Turkey, Tunisia, and Italy are expected to reveal much of the urban landscape of the period.

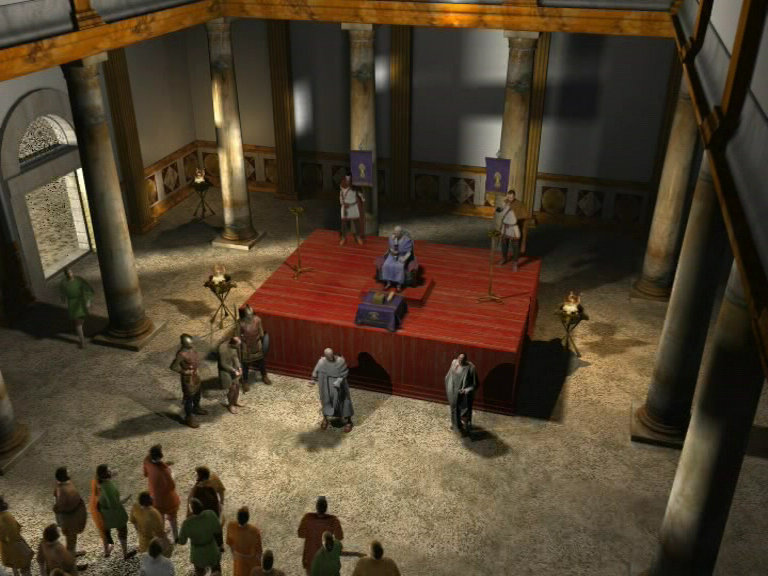

‘Few films or TV programmes seek to visualise everyday life in late antiquity. Most people simply cannot imagine the Mediterranean cities of this period, such as Carthage as known to Augustine, Jerusalem as known to Mohammed, or Constantinople as known to Justinian,’ said Dr Lavan.

‘This was a critical period in the development of European civilisation, yet it is remarkable how little is known about the daily rhythms of city life. When most people close their eyes they can probably imagine urban life from earlier periods, in places like Rome or Pompeii, but that is not the case for late antiquity.

‘We’ll be looking particularly at how people made use of the urban public space. We hope to reconstruct not just architecture, but a more vivid image of daily life in Constantinople, with lawyers, clergy, urchins and prostitutes going about their business.’

Dr Lavan, of the Department of Classical and Archaeological Studies, said that in many cases excavations of late antique sites revealed well-preserved evidence. This is because the period formed the final layer on most sites before they were abandoned.

‘Buildings often survive intact to their roof-line, with internal fittings such as ovens, cupboards and shop-counters. Statue bases can also survive in situ on public squares, while pavement markings, along with graffiti and minor official notices, reveal the locations of market stalls or political meetings,’ he added.

It is expected that the research, which will published as both scholarly tome and an illustrated catalogue, will help film-makers, popular authors and museums produce better reconstructions of city life in late antiquity, and thus make the period more accessible to a wider public.

(image: Late Roman Law Court, reconstructed by Archaeological Service of Alcala de Henares, in conjunction with the project)