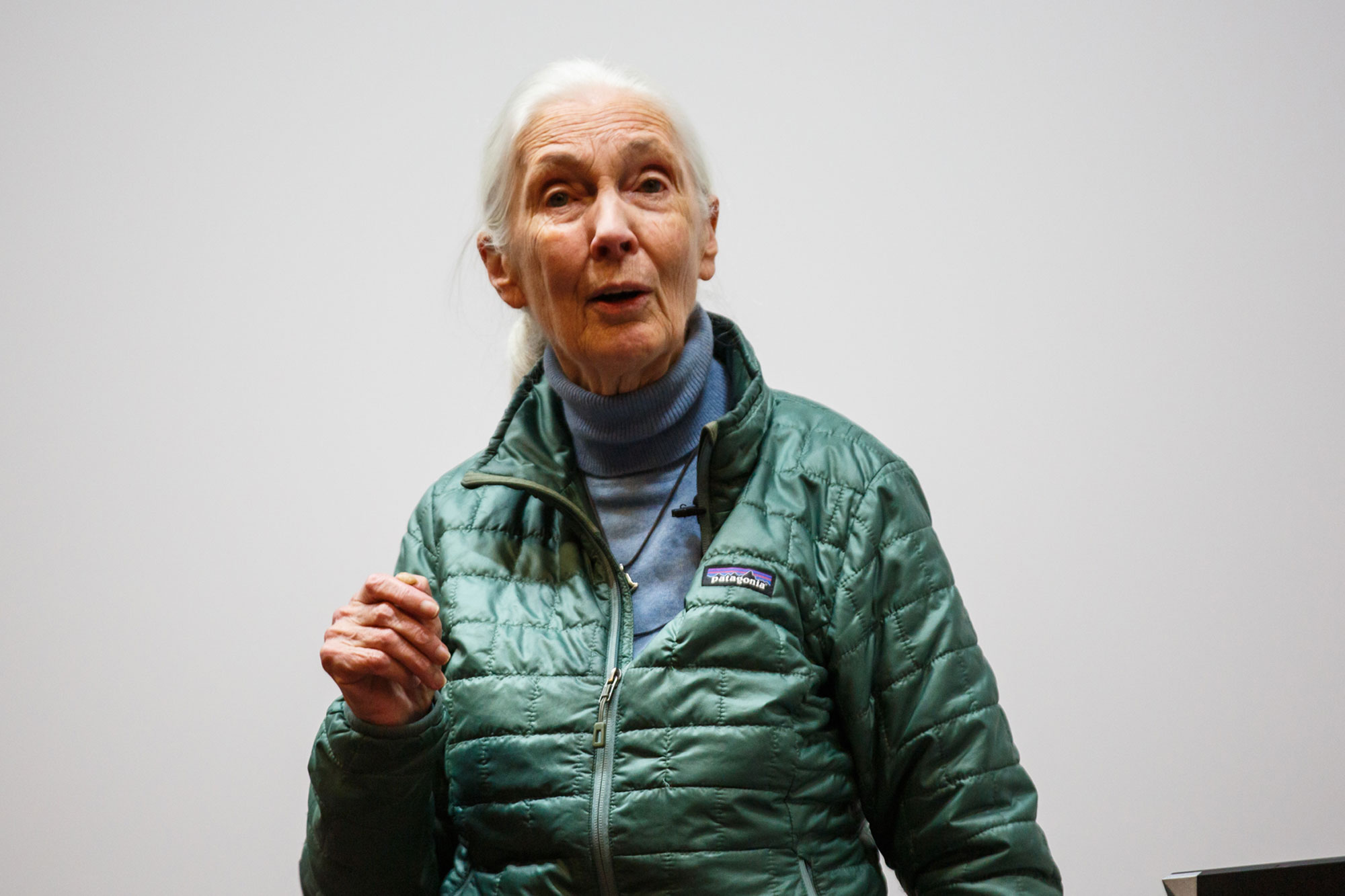

“Every day you live, you make an impact and you get to choose what sort of impact you make.” When Dr Jane Goodall ended her public talk with this, we felt compelled to rise to a standing ovation for two minutes, to which the celebrated conservationist warmly responded with a smile – “Responses like this keep me going: you are all a reason for hope.”

Let me go back to the 25th of February 2020, the day of the much-anticipated lecture. It was hard to believe that Dr Goodall, yes, the Jane Goodall!, was not only on our campus, but addressing staff and students belonging to the Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology (DICE).

The Woolf Lecture Theatre was filled to capacity to mark this year’s annual DICE Lecture delivered by Dr Goodall and entitled ‘Gombe and Beyond: Chimpanzees, conservation and change’. Professor Bob Smith, Director of DICE, formally opened the evening with a short overview of the research centre, detailing its formation and near-30 year history, and how its name was chosen in honour of Gerald Durrell’s lifelong commitment to conservation. Bob also shared the fantastic news that DICE had, earlier that month, been presented with a prestigious Queen’s Anniversary Prize before welcoming Dr Goodall to the stage.

Greeting an audience of 500, Jane used a series of unfamiliar guttural sounds: this was the welcome given to visitors in Gombe National Park. She went on to describe her upbringing and how she came to study chimpanzees at Gombe, before comprehensively detailing her life’s work and hope for the future:

Jane had a typical childhood, except for the fact that she used to pretend to her friends that she could understand what animals said – a juvenile Dr Doolittle. Jane would spend hours patiently observing the behaviours of her own pet. Her passion for wildlife paved a way to follow her dream and go to Africa, living with animals and observing them, noting down their behaviours. This ‘career choice’ for a lady in her twenties was considered strange by many of her peers, but her mother, Margaret, had given Jane her blessing to pursue this opportunity. Margaret took Jane’s ambition seriously and encouraged her to work exceptionally hard and take advantage of anything that was offered, no matter how adventurous: she was nurturing a fledgling scientist!

Jane soon learned that following your dream job was not all that easy in reality, and could only be fulfilled with a lot of dedication. She worked as hard as she could to collect money to go to Mombasa, a coastal city in Kenya. During that same trip, she met Louis Leakey, a renowned anthropologist and palaeontologist who was looking for someone to study chimpanzees in Tanzania. Luckily, Jane got a chance to work with him as his secretary, quenching her thirst for learning about animal and plant biology. Leakey sensed Goodall’s avid interest in animals and chose her for the expedition to Tanzania. Jane returned to London to learn everything possible she could about chimpanzees and primates before venturing into the jungle, accompanied by her mother, to start her remarkable journey.

Her early field days were more disappointing than she imagined. Jane used to be frustrated with the fact that, despite her many attempts to learn first-hand about chimpanzees, she was not making any progress. The chimps used to run away from her as they were not familiar with human proximity. However, Margaret’s unflagging reassurance boosted her morale. Through perseverance and determination, slowly but surely Jane began to learn novel things about the behaviour of the chimpanzees, observations that had not been recorded before in scientific literature.

For example, Goodall learnt that chimps use twigs to eat termites from their mounds, which no one had witnessed before: it proved that humans were not the only species who used tools. She also witnessed both the playful side of chimpanzee behaviour and the darker side, how they could be aggressive and violent toward one another. The other remarkable discovery that Jane made was witnessing how chimpanzees use non-verbal communication like humans.

However, she needed hard evidence to break widely-held assumptions such as the aforementioned belief that humans were the only species to practise tool use. The National Geographic assisted her in documenting the chimps’ behaviours by sending a photographer, Hugo van Lawick, out to Tanzania. So, despite Goodall’s initial disenchantment with long-established scientific orthodoxies about primates, with the evidence that she and Lawick recorded, people came to believe and accept her findings about humankind’s closest living relatives.

All species, no matter how small or insignificant they may be, have a role to play in making this world a beautiful place to live. Jane wanted to communicate this in a means that would be taken seriously. She enrolled at Cambridge to undertake a PhD under the supervision of a renowned ethologist (one who studies animal behaviour), who taught her how to write about what she had observed in a way that did not lead her to criticism. For instance, instead of claiming that baby chimpanzees experience jealousy, she could write that a baby chimp behaves in such a way that, if it were a human child, we would say it was jealous. After her PhD, Dr Goodall went back to Gombe and built her own small research station, which facilitated other young students to study chimpanzees, learning about their behaviour and expanding upon Jane’s initial research.

Her groundbreaking scientific efforts aside, a conference held in America entitled ‘Understanding Chimpanzees’ that Jane attended in the 1980s became an eye opener, paving her way towards animal activism. She learnt about the painful truths of captive situations where baby chimpanzees had been abducted from their mother and trained for entertainment: even worse was that they were kept alone in cages in medical research labs. After this, she started to work beyond Gombe, concentrating more on activism and trying to address such diverse issues as bushmeat trade, hunting of wild animals and the spread of infectious diseases across species.

Dr Goodall’s work was novel in many ways. While she focused on animal welfare, behavioural research and so on, she equally emphasised awareness of human livelihoods in developing countries. Jane prioritised issues like poverty and wealth inequality, illiteracy, ill-health and deforestation. It was this concern for humans and their environment that led her to create the Roots and Shoots programme for young people at the Jane Goodall Institute (JGI), which has now reached 65 countries.

Participants design community-led, environmentally-sustainable projects with the enterprise aiming to empower local populations, be it women to make them more independent or in job creation, and training communities to use existing technology like GIS (Geographic Information Systems) and satellite imagery to make them more adept at land-use planning. With methods such as this, the JGI sensitises people to the fact that conserving habitat and regulating ecosystems is not just for wildlife, but for their own future.

One of Dr Goodall’s mottos is that, when head and heart work in harmony, true human potential shows itself. She believes that, due to the disconnect between the human brain and heart, we are destroying our beautiful planet, causing a climate crisis. We have compromised the future of young people, who will not inherit the same planet that our ancestors gave to us. However, Jane is quick to stress: it is never too late to act together to slow down climate change and the global destruction of animal and plant life.

If all of us could strive to learn from Dr Goodall’s tireless work, we have hundreds of reasons to be positive. Like Jane herself, whilst we should not neglect challenges like poverty, unsustainable livelihoods, corruption and escalating human populations, we must be hopeful. For we have an empowered, conscientious youth, innovative technologies and that indomitable human spirit to tackle the global climate crisis. And we must never lose faith in the resilience of nature.

In what was an infectious and inspiring evening, Dr Jane Goodall showed herself to be a pillar of determination and intellectual curiosity, one who has never lost sight of the importance of hope. As the talk came to a close, Jane led the audience with a communal chant that resounded around campus.

“Together we can! Together we will!”

Text by Reshu Bashyal, currently studying for an MSc in Conservation and International Wildlife Trade at DICE.