As someone who has researched the prominence of climate and ecological breakdown in David Attenborough’s documentaries, I was disappointed by the first episode of the legendary filmmaker’s latest series, Seven Worlds, One Planet. Although I was enthralled by nail-biting scenes of uncertain survival, like his previous work, it betrays the natural world by showing it as mostly untouched by human impacts.

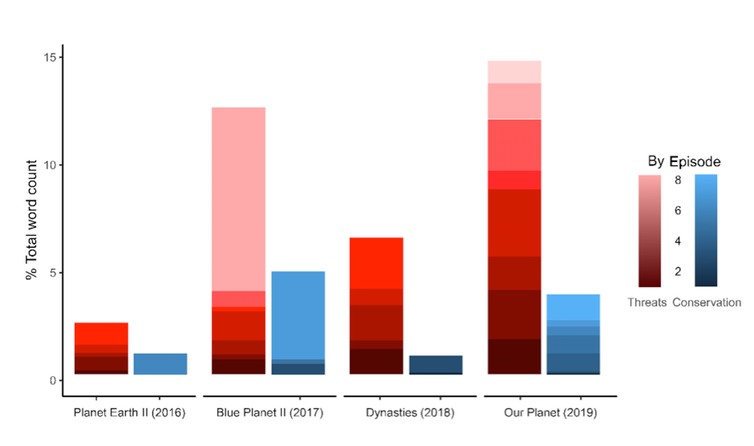

His last documentary, the Netflix production Our Planet, had taken a small step forward in this regard. Along with colleagues from Newcastle, Bangor, and Oxford, I analysed scripts from Attenborough’s last four documentary series, and we found that Our Planet discussed both conservation threats and successes more often than his previous work. Nearly 15% of the total word count of the Our Planet scripts focused on what is not well with the natural world. While this was only slightly more than Blue Planet II at 12%, talk of human impacts was woven into every episode rather than being the subject of a dedicated final episode.

Our Planet also shared conservation successes in every episode. While Blue Planet II devoted slightly more of its overall script length to such issues, again this was mostly concentrated in the final episode and not incorporated throughout the series.

However, while Our Planet contained a few visually shocking scenes (walruses spring to mind) that prompted discussion of climate breakdown in the media, the series – like those before it – was almost bereft of scenes that directly showed the abundant ways in which humanity has devastated the natural world.

A sideways step

The first episode of Seven Worlds, One Planet showed visually breathtaking scenes of the harshness of Antarctic life, but yet again for the most part nature appeared devoid of human influence. Admittedly, it is more difficult to directly depict the effects of humans on a continent where no humans actually live, and hopefully later episodes will be bolder. But even in this episode, melting ice and calving glaciers were mentioned only briefly, and these changes to the climate were rarely explicitly highlighted as caused by human actions.

The exception was a vignette in which we were shown an abandoned whaling station, and told how humans caused whale numbers to crash, before their recovery following a whaling ban. This reflected a common theme of success stories in the episode – scenes capturing the struggle of albatrosses and penguins against the effects of climate breakdown also ended in triumph.

This is not a bad thing – optimism can be a useful tool in driving engagement and positive change. But to be effective, it needs to be accompanied with a sense of how individuals can contribute to keeping the good news going. For example, the whaling section ignored the role of social movements in pressuring governments to institute the whaling ban.

Seeing smelly, seasick cameraman Rolf fighting tears when ruminating on the perilous future of the penguins he filmed was perhaps the most powerful scene of the show. In connecting human guilt and sorrow to the penguins’ plight, it intertwined humanity and nature in a way not managed by the rest of the episode. But, again, the segment left no sense of how we all can help.

A force for change

Nature documentaries have great potential to be a force for good. They can increase willingness among viewers to make personal lifestyle changes, increase support for conservation organisations, and generate positive attitudes towards an issue, which may in turn make policy change more likely.

But the way they’re framed is important. Attenborough’s position is that presenting a doom and gloom picture of the living world could be “alarmist” and a “turn-off” and prefers to focus on the marvels of nature to inspire connection. But the one major exception to his usual approach had major social impacts.

Almost 40% of Blue Planet II’s final episode was dedicated to human threats to the natural world and homed in on plastic pollution. This focus helped spark a public movement against single-use plastics. Within a year, the UK government announced its intention to ban the sale of plastic straws and drink stirrers and corporations such as Starbucks and McDonalds decided to stop stocking plastic straws. A box set of the series accompanied by a letter from Attenborough was gifted to Chinese president Xi Jinping during his 2018 visit to the UK – which concluded with the announcement of a joint plan to tackle plastic pollution.

We need more research to pin down exactly how the portrayal of nature in documentaries affects our willingness to help save it. But I’d bet that it would be a lot harder to ignore the link between high-consumption lifestyles and desolation of the natural world if the pervasiveness of commercial agriculture, mining and transport infrastructure in natural landscapes was more visible. Instead of brief references to climate change and cute chicks fighting to survive against the odds, we need to be confronted with the stark reality of the destruction resulting from humanity’s actions.

I believe that Attenborough and the production teams behind Seven Worlds, One Planet are truly passionate about the environment. It is brilliant that they are bringing the beauty of the living world to our screens, but it is time to go beyond inspiration. Show us what we have done wrong, show us how it is affecting us, and then tell us how we can help.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.