It has become a tradition for first year students at the School of Anthropology and Conservation to go on a field trip to the principal ethnographic museums of Paris: the Musée De L’Homme—a general anthropological museum concerned with human diversity and evolution; and the Musée du Quai Branly—a museum of non-European art that features one of the world’s richest collections of the arts of Oceania, Africa, America and Asia. This offers a unique opportunity for students to gain first-hand insights into the work an anthropologist could do after they graduate and addresses some of the major issues of the subject and how they relate to the history of anthropology.

The relationship between museums and anthropology dates back to the earliest stages of both. When museums, in the form of exhibition halls open to the public, came into being in the early 19th century, they had predecessors dating back centuries known as ‘cabinets of curiosities’. These displays were normally owned by the aristocracy and contained collections of notable and unusual objects from across the globe, the world’s diversity gathered into one space.

The items collected were not seen as everyday objects, but rather as examples of the extraordinary, especially regarding other peoples’ ways of life. In the 19th century, as museum spaces became more formalised, their collections corresponded to the dominant idea of anthropology, which was one of primitivism, an interest in non-Western, ‘exotic’ cultures informed by the emerging nationalisms of Europe.

Anthropology’s early scholars did not themselves go into the field, as is now the accepted practice. They stayed at home and let the ‘world come to them’: they were thus called ‘armchair anthropologists’. What they did was to study stories, documents, records and objects that were brought to them by such people as travellers, missionaries, traders, or colonial administrators. On the basis of that, they conceived a supposed genealogy of human life on earth. They compared objects of all kinds across different cultures, such as spears, axes, canoes, pottery etc. Their aim was to identify the ‘first’ prototype, that is, the most ‘primitive’ example, and then come to understand how the artefact spread around the earth as the practice of usage became more commonplace (there is an excellent display of this at the Pitt-Rivers Museum in Oxford).

As research moved toward spending time in the field to study the modes and practices of indigenous cultures up close (ethnography) in the 1920s, anthropology became more critical and a split began to occur between the discipline and traditional museology. Later still, many anthropologists came to oppose the colonial ideologies that were implicit in most of the museum collections.

This led to a complete break between museology and academic anthropology. When colonialism finally came to an end in the second half of the 20th century, the museums contained a lot of history that needed to be recontextualised. At this point, a new, postcolonial approach emerged. Since the late 1980s, academic anthropology started to be interested once again in material culture and a reconciliation began. As a result of this, a complete rethinking of the role of anthropological museums took place throughout Europe and North America, often increasingly in dialogue with the global south.

One event that caused much debate in academic circles was the solution adopted by the French government, led by the then-President Jacques Chirac. He proposed to gather all ethnographic collections of the country and re-divide them between three main museums: the Musée de l’Homme (dealing with the evolutionary history of mankind), the Musée du Quai Branly (dealing with non-European art) in Paris, and the Musée des Civilisations de l’Europe et de la Méditerranée (dealing with the art and cultures of the Mediterranean basin) in Marseille.

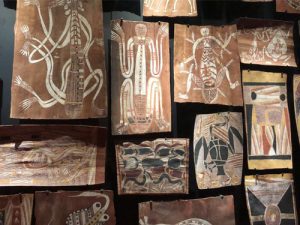

Today, each of them hosts absolutely distinctive collections and presents exhibitions of the greatest human value. In particular, the Musée du Quai Branly is a great learning experience for students of anthropology who gain first-hand contact with ethnographic objects from all over the world. Yet the French approach separates off Middle-Eastern and European cultures from all ‘Other’ cultures—which precisely is something that most academic anthropologists see as a source of concern. This division was, and still is, seen as a way to reproduce a division of the world into developed or ‘civilised’ parts, and underdeveloped or ‘primitive’ parts; into the ‘West’ and the ‘Rest’.

However, these museums still constitute an enlightening experience, providing first-year students with a unique opportunity not only to experience material culture from around the globe, but to engage critically with the way, rightly or wrongly, European cultures have taken it upon themselves to catalogue and exhibit artefacts that once belonged to other communities around the world. And it was also great to see the Eiffel Tower from the elevated plaza where the Musée de l’Homme stands!

I hope that many future generations of Anthropology students at the University of Kent continue to get the chance to visit these museums in Paris as part of their training as anthropologists.

Text provided by Moritz Zielinski (University of Kent/University of Mainz).