Ben Mott, Stage 2 Wildlife Conservation student and media representative for the ECS Society writes about the rise in eco-fascism, and why it is so dangerous.

On the socio-political spectrum, the far-right, and to an extent the established ‘right’, have historically been at the forefront of climate denial. Whilst this notion has not disappeared, as acceptance of the severity and imminence of the global ecological crisis is becoming increasingly established, it is inevitable that some on the far-right do become twisted ‘environmentalists’ – or to be more precise, eco-fascists.

Eco-fascism has been seen in notable terrorist accounts in recent times; fresh in memory will be organic-eating Jake Agnelli, or the QAnon Shaman, one of the terrorists who stormed the Capitol and whose social media revealed interest in “cleansed environments”. Patrick Crusius, who murdered 22 Hispanic people in a deliberate targeting in 2019, wrote in his manifesto “An Inconvenient Truth” (sound familiar?) that “If we can get rid of enough people, then our way of life can be more sustainable”. Earlier that year, in Christchurch, Brenton Tarrant murdered 51 people across two mosques. In his manifesto, he wrote “there is no nationalism without environmentalism”.

Eco-fascism places blame for environmental degradation on over-population and mass immigration, which sees populations move out of their homelands. A wide array of influences contributed to the emergence of eco-fascism: Malthusian concerns regarding over-population in the global south driving environmental destitution, social Darwinism determining that only the fittest deserve to survive, and even “deep ecology”. Deep ecology, which argues for human submission to Mother Nature, letting nature take its course, is indistinguishable from the other two in that there is a deliberate failure to employ any level of analysis beyond the superficial in order to suit pre-conceived racist and fascist agendas.

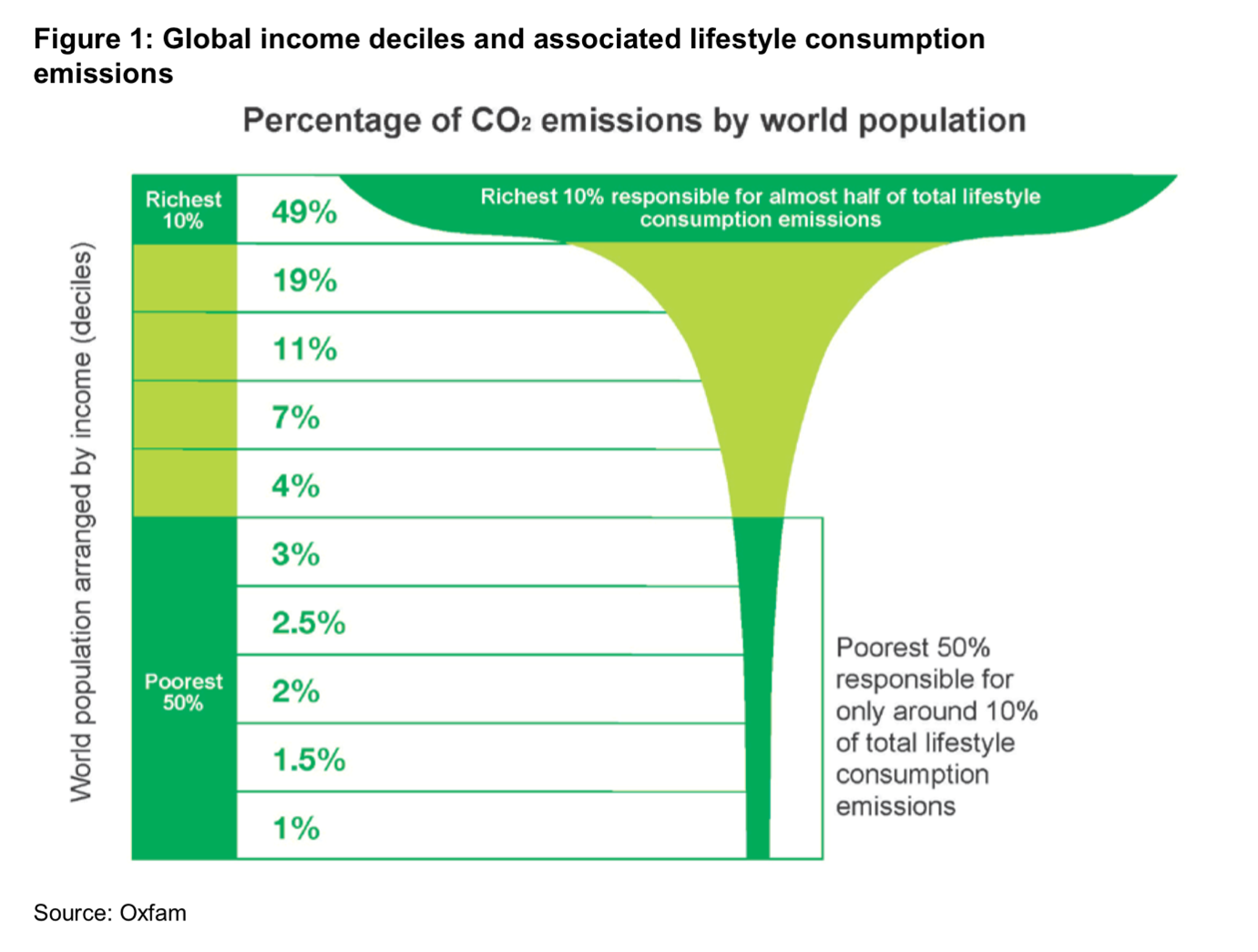

Sure, there are lots of people on the planet. But studies generally foresee that the population will peak and stabilise around the 10bn mark by the end of the century. The issue is not one of population but of distribution: which stems from colonialism and exploitation of labour, and is sustained by neo-colonial, neoliberal world politics. It is well known that the climate crisis is fuelled by the consumption of the richest in the world. It is this group of people who control distribution of resources; this group of people who have benefitted from centuries of exploitation of indigenous peoples, the global south, women, workers, people of colour, and many other minority groups that face discrimination.

If cries of overpopulation are to be made, then they must be qualified by a historical context of population growth and contemporary awareness of the maldistribution of resources, both of which serve rich western nations beyond all else. Failing to undertake a deeper analysis of the forces driving the ecological crisis – the same driving social crises – is at best lazy and privileged; at worst, as shown, it leads down a slippery slope.

Even the term “Anthropocene”, which has wound its way into contemporary environmental discourse, is complicit in this shallow analysis, insofar as it places blame for the breaching of planetary boundaries on every human’s shoulders. This is blatantly false, serving to deflect attention away from the root causes. A growing number of scholars prefer “Capitalocene”, referring to capitalism and the capitalist class, which is a far more accurate reflection of what is fuelling this epoch of destruction – not the Anthropos.

See the original post about eco-fascism on the E.C.S. Society instagram page, @e.c.s_kent_society