Historically snubbed by exclusionary conservation, the role of Indigenous and local communities is integral to achieving the UN’s ambitious 2030 global biodiversity agenda. Over 1.65 billion Indigenous Peoples, local communities and Afro-descendants hold the key to preventing a global biodiversity collapse. Recognising tenure rights of Indigenous and local communities is projected to cost less than one percent of the cost of resettling populations in biodiverse areas.

These are the key findings of a study conducted by the Rights and Resources Initiative. The study was co-authored by Gwili Gibbon, currently studying for his PhD at the Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology (DICE), and Thomas Worsdell, and alumnus from the MSc in Ethnobotany programme, with substantial contributions provided by postgraduate alumni Tessa Ullmann and Joana Caneles alongside Professor Bob Smith, Director of DICE.

With the UN, NGOs and conservationists advocating to place 30 percent or more of the planet’s terrestrial area under formal conservation by 2030, a new study cautions of the potential costs of using exclusionary conservation approaches to meet those targets. It also sets out how to achieve them: by empowering the Indigenous Peoples, local communities and Afro-descendants who have customary land rights to at least half of the Earth.

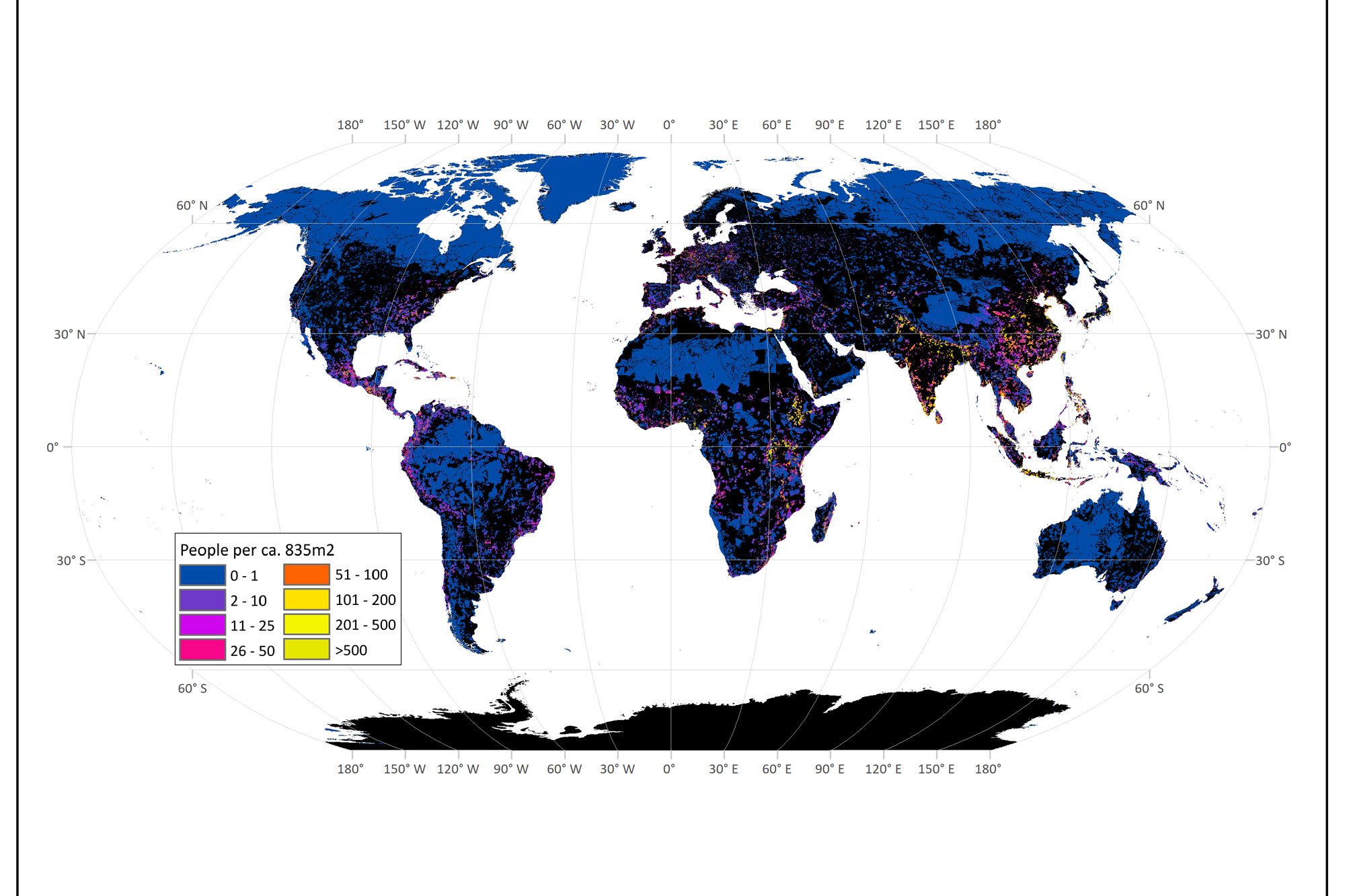

The study conducted by the Rights and Resources Initiative (RRI) and produced in collaboration with the Campaign for Nature shows that over 1.65 billion Indigenous Peoples, local communities and Afro-descendants live in the world’s important biodiversity conservation areas. Another finding shows that 56 percent of the people living in important biodiversity conservation areas are in low- and middle-income countries; whereas only 9 percent live in high-income countries. This underscores the disproportionate impact of conservation on the Global South.

“This report shows that, as far as both the science and economics are concerned, investing in Indigenous peoples’ and local communities’ land and resource rights should be a primary strategy for reaching global biodiversity targets,” said Brian O’Donnell, Director of Campaign for Nature. “By adapting rights-based conservation, the 190 countries negotiating the UN’s post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework have an important opportunity to protect the planet and significantly expand human rights at the same time.”

While not all protected areas or conservation approaches conflict with Indigenous Peoples, local communities and Afro-descendants, many protected-area approaches have sought to preserve biodiversity by relocating people and prohibiting access or traditional use within protected area boundaries. The study estimates the value of those public protected-area approaches, assessing the cost of relocating between 1.2 and 1.5 billion people living in unprotected, important biodiversity conservation areas to range between four and five trillion US dollars.

Contributing to the growing body of evidence

The report builds on prior research showing that Indigenous Peoples, local communities and Afro-descendants have customary land rights to at least half of the world’s terrestrial area but legally own just 10 percent.

“This report reinforces peer-reviewed findings that already show how Indigenous Peoples, local communities and Afro-descendants are far more effective than governments at protecting ecosystems and protecting forests, especially when given formal rights that allow them to continue protecting their territories,” said ethnobotanist Thomas Worsdell. “Supporting their agency and self-determination is the most cost-effective path to achieving global biodiversity goals.”

Raina Thiele, who is Dena’ina Athabascan and Yup’ik, and an advisor to the Campaign for Nature on Indigenous issues, added that any approach ignoring Indigenous and community ownership brings substantial risk of social conflict and resettlement.

“The conflict and violence around some public, protected areas demonstrate that exclusionary approaches cannot continue, much less expand to reach global targets,” said Thiele, who worked with the Obama Administration on tribal issues. “Some conservation organisations recognise this and have shifted practice towards rights-based conservation: others now need to follow suit.”

That data draws on financial forecasts of resettlement action plans produced by the International Finance Corporation among others. The authors project the cost of recognising the tenure rights of Indigenous and local communities at less than 1 percent of that of resettling populations in biodiverse areas, based on data from Peru, Indonesia, India, Nepal and Liberia.

“This is the first study to quantify the potential contribution of Indigenous and local communities to achieving global scale biodiversity conservation outcomes,” said Dr James Allan, another co-author, conservation scientist and Research Fellow in Global Ecology at the University of Amsterdam. “The work clearly shows these people are key partners with a major role to play. Conservationists must capitalise on the moral and financial win-wins available through a rights-based approach.”

José Francisco Cali Tzay, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, also endorsed the report’s findings. He said, “Throughout conservation’s chequered history, we have seen exclusionary conservation as a gateway to human rights abuses and militarised forms of violence. We now have evidence that this approach is also economically devastating. Paying Indigenous Peoples to abandon lands they have historically protected better than governments and private entities is wasteful and furthers past wrongs.”

The report includes actionable recommendations for intergovernmental organisations and institutions, conservation organisations and donors, and governments. These include urging these actors to adopt the Gold Standard principles for best practice for recognising and respecting Indigenous, Afro-descendant and community rights in the context of climate, conservation and sustainable development actions. Andy White, RRI’s Coordinator, said the report will be used as a baseline to build upon further data collection on regional and country level. Those findings will be released in early 2021.

“What the global findings tell us is that we are not going to get to the ambitious conservation agenda through business as usual,” he added. “It is time we all embrace the urgency of ensuring that land rights must be a foundation, not an afterthought, in the conservation agenda.”