President Joko ‘Jokowi’ Widodo’s administration will continue giving permits for local communities and indigenous peoples to manage forests under the Social Forestry Scheme during his second term.

No official target has been announced this time. Jokowi had previously issued permits to local and indigenous peoples totalling 3.5 million out of the national target of 12.7 million hectares of land, or 27%, throughout the country.

The Social Forestry Scheme has five forms. These are Village Forests, Community Forests, Community Plantation Forests, Customary Forests (forests within the territory of indigenous communities) and Collaborative Forest Management (partnerships between state-owned or private companies and local communities to manage forests).

The aim of the scheme is to reduce poverty by giving people access to manage forests and get economic benefits. In addition, the project aims to curb deforestation.

Our study of the management of Village Forests in Kalimantan island between 2008 and 2014 shows the scheme can work to reduce poverty and curb deforestation. The benefits were greatest in areas surrounding protected watersheds and limited production zones, where quotas limit logging activities.

This is how it works.

Our study

We assessed 41 areas holding permits for Village Forests across Kalimantan. These are part of 1.4 million hectares of forests and degraded lands that have been granted Village Forest status to date.

These areas were chosen because they held the permit to develop Village Forests since 2009.

About 2,000 people live around each of these Village Forests.

We compared the deforestation rates in the Village Forests with the rates in forest areas without the designation between 2008 and 2014.

We also compared the change in poverty rates in villages surrounding these forests with the rates in villages without Village Forests over the same period.

We used 18 indicators of poverty representing five dimensions of welfare: basic (living conditions), physical (infrastructure), financial (income support), social (social security and absence of conflict) and environmental welfare (natural hazard prevention).

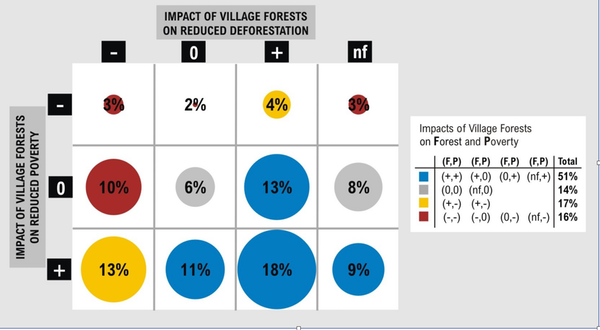

We found poverty and deforestation rates fell in more than half of the 41 Village Forests (51%) we surveyed.

However, the Village Forests showing both declining poverty and deforestation rates are only 18% of the total – 13% of the Village Forests only managed to curb deforestation in their areas.

In conclusion, Village Forests under the social forestry scheme have reduced both poverty and deforestation rates, but not in all cases.

The most effective Village Forests

The most effective locations for Village Forests are watershed protection zones and limited production zones.

This is due to the limited exposure to people and logging activities in these areas. These Village Forests are typically located in remote areas, far from big cities.

The deforestation rates are generally mild due to low logging activities. And, while the poverty rates are high, the villagers, with the help of local NGOs, get money from preserving the forests by replanting trees and monitoring.

The villagers are still receiving these economic benefits and continue to improve their livelihoods to become more self-reliant.

This is not the case for other Village Forests, which still have high rates of encroachment and peat fires.

In our study, we found that villagers located in areas designated for timber plantations and palm oil concessions are the least effective at implementing Village Forest schemes.

This is because major plantation companies most likely own and control these zones. These companies carried out their activities on industrial scales, promoting deforestation.

The social welfare analysis showed these communities had not yet benefited from the scheme.

How to maximise Village Forest benefits

Based on our findings, we have four suggestions to maximise the Village Forest goals of alleviating poverty and reducing deforestation:

1) Focus on improving basic welfare, generating income from non-timber forest products (such as rubber) and recognising indigenous or traditional knowledge to manage forest.

2) Provide extra human resources and capital assistance to support these programmes and to ensure long-term restoration of degraded peatland, especially Village Forests near timber plantations and oil palm concessions. Around 40% of Social Forest schemes are located in those areas in the provinces of Riau, Jambi, South Sumatra, Central Kalimantan and the southern part of West Papua.

3) Integrate social forestry schemes near timber plantation and palm oil concession zones into existing plantation certification mechanisms, such as the Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO) or the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO). This would give villagers a bargaining position towards plantation concessions and smallholders (under ISPO or RSPO scheme), especially on finance.

4) Publish the Ministry of Agrarian and Spatial Planning’s data. This is vital to improve transparency, as well as to reduce the risk of finger pointing and of essentially going back to square one.

This article by Truly Santika, Dr Matthew Struebig, Reader in Conservation Science at the Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology (DICE), and Sugeng Budiharta is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.