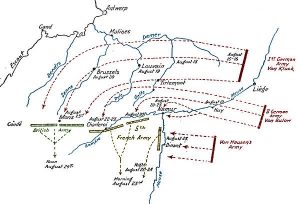

When Germany invaded Belgium on 4 August 1914, Britain declared war on Belgium. The German troops reached the southwest of the country in less than three weeks. On its path, the Germany army left a trail of destruction. From Liège over Aarschot and Leuven to Brussels first and onto Namur and Mons next, the German soldiers also committed atrocities.

Figure. German troops enter Belgium from the East and head west/southwest. They reach Dinant, Charleroi and Mons on 23 August. The northern and north-western parts of Belgium are virtually left untouched for another month. (Source: Wikimedia)

The first few weeks of the First World War in Belgium are also called ‘the Rape of Belgium’. In retaliation for fierce opposition, the German army used a tactic of schrecklicheit: they shelled towns and villages, set houses alight and executed civilians. More than 5000 civilians died in the first month of the war alone. At Tamines, a tiny village near Namur, nearly 400 people were shot. The atrocities and the stories that come with them triggered a mass movement of the population. In all, nearly one and a half million of Belgians, one in five of the entire population, were to go on the run to reach safer grounds abroad. How many more were overtaken by the advancing front lines is not known. When the Germans started shelling Mechelen, in-between Brussels and Antwerp, nearly 55,000 of the 60,000 inhabitants fled the city.

As the German army headed for France, the movement of the troops pushed Belgian civilians westwards, towards the coastline or to France via the remaining corridor west of Mons, or more to the north of the country. There, hundreds of thousands of internally displaced persons sought protection in and near the fortified port city of Antwerp, which was deemed the final safe haven. The Belgian monarch, King Albert, the government and both Houses of Parliament had retreated to that national redoubt. About one million people looked for safety in the area.

Eventually, when the Germans turned to Antwerp and besieged the port city, a further mass exodus was triggered. The government left Antwerp for Le Havre, France. King Albert sent his children to Britain and joined his troops. Large numbers of internally displaced persons crossed the river Scheldt and headed for the coast, hoping to cross the Channel, to Britain. Over one million Belgians crossed the border into the Netherlands in less than a fortnight. Of those, many returned soon after Antwerp had fallen, but a sizeable number travelled on to Britain.

Belgians arrived in Britain in various waves. Small numbers, including the royal children, arrived in August. In September, the British government organised a shipping link between Antwerp and Tilbury, but these did not suffice for the increasing numbers. Soon, Belgians were labelled upon arrival: the more well-off families obtained a pink label and were sent on, treated well. For these Belgians, offers of places of accommodation far exceeded demand, if they did not already had the means to sustain themselves. Other Belgians were given a blue label and were sent on to the dispersal centres in London (Alexandra Palace first, Earl’s Court next) or to a location of reception straightaway.

Although in October very large numbers crossed the Channel and most Belgians arrived in Folkestone, they also landed elsewhere, often without proper registration. And yet, a wave of empathy met the Belgians. Even today, more than a hundred years later, stories emerge of how local communities turned up in their droves to be welcoming only a handful of Belgians.

By the end of 1914, nearly 100,000 Belgians had crossed the Channel. Six months later, this number had grown to about 175,000. In total, during the course of the war, over a quarter of a million of destitute Belgians had visited Britain, although there were never more than 175,000 in Britain at any one time, with roughly one in three residing in the greater London area, and most of those along a corridor on the River Thames.

In Britain today, the story of about a quarter of a million Belgian refugees during the First World War is little-known. There are many reasons for this. Most importantly, however, the Belgians came as they went. By Easter 1919 nearly all of them had returned to Belgium. Also, even during their stay in Britain the Belgians disappeared from view. This is where the sojourn of the Belgians in Britain becomes both interesting and complicated.

Initially the image of the ‘Belgian refugee’ and the atrocities they had to endure was a very useful image in maintaining popular support for the war cause (‘Remember Belgium’). However, the war was not over by Christmas. The Belgians needed more than reception, accommodation, subsidized support and charity. After the Shell Crisis of May 1915, tens of thousands of Belgians were employed in the war industry across Britain. Where a true Belgian colony around a particular factory developed, legacy stories lasted until today. The best examples of local histories involving Belgian labour colonies are the ones from Elisabethville, Birtley, near Newcastle, and the Pelabon works in Twickenham/Richmond.

Belgian children disappeared from view as well. Although most of them were incorporated into the British education system, thousands of Belgian children went to entirely Belgian schools established in Britain especially for that purpose. The Belgians also relied on an intricate spread of exile newspapers and journals.

By the end of 1915, the Belgians in Britain disappeared from view into the factories and schools and they were reported on mainly in their own newspapers.

Another issue that blurred the memory of the Belgians in Britain was the thin line, if existing at all, between refugees and soldiers. Belgian soldiers were being sent to Britain to convalesce from mid-October 1914 onwards. Increasingly, very large numbers of Belgian soldiers recovered or took their leave in Britain. Belgian army and army intelligence services settled in the southeast. Some Belgian factories in Britain were virtually manned by long-term convalescing Belgian soldiers only.

At the level of everyday life, many local histories and numerous personal stories still need to be uncovered, and when they will be they will provide the bottom-up approach to social and cross-cultural history that resonates today still. The history of the Belgian refugees at Tunbridge Wells is a prime example of such a unique project that combines current-day community spirit in uncovering the many Belgian stories in the town and the wider area with a contribution to the increasing literature as well as understanding of this little-known history of welcome, accommodation and opportunity.

Sources

- Baker, Helen and Christophe Declercq (2016) ‘The Pelabon Munitions works and the Belgian village on the Thames: community and forgetfulness in outer-metropolitan suburbs’, Immigrants & Minorities, Historical Studies in Ethnicity, Migration and Diaspora, Vol 34:2: British responses to Belgian Refugees during the First World War, available online here.

- Declercq, Christophe (2014) Belgian refugees in Britain, The Low Countries, online.

- Horne, John and Alan Kramer (1994) ‘German “Atrocities” and Franco-German Opinion, 1914: The Evidence of German Soldiers’ Diaries’, Journal of Modern History, online.

- Huws, Hanna and Christophe Declercq (2016) Impact of World War 1 – Wales Welcomes over 4500 Belgian Refugees, Wales For Peace, online

- Vermandere, Martine (2017) Draaiboek Vluchten (unpublished script for a virtual exhibition that will go online later on in 2017, http://www.belgianrefugees14-18.be/).

- Image, Wikimedia, online.

Article: Dr Christophe Declerc.