“These brave Belgian people have nobly done their share in opposing the German aggression, and let us do our best to show our gratitude.”

Councillor C.W. Emson, Mayor of Tunbridge Wells, in October 1914

That Tunbridge Wells had its own “Belgian Colony” during the First World War is a largely unknown part of the town’s history, even though after the war members of the town’s Refugees Committee, notably its former Mayor Councillor C.W. Emson and social pioneer Amelia Scott, were decorated by the King and Queen of the Belgians in recognition of their work.

As the crisis unfolded in late August 1914, Tunbridge Wells was quick to respond, and individuals came forward to offer accommodation and help.

One such offer came in early September, when Mr and Mrs Johnstone of Burrswood, Groombridge offered Clayton’s Farmhouse in Ashurst and formed a small committee to prepare for arrivals. By the end of the month the first group of men, women, and children had arrived [1], many of them from the village of Herent near Leuven, bringing tales of the horrors they had seen and experienced.

Herent War Memorial showing names of civilian casualties “Onze martelaars”

(© Alison Sandford MacKenzie 2015)

By this time there was a War Refugees Committee (WRC) up and running in London, and a War Relief Committee in Folkestone, and the Mayors of all large Boroughs outside London, as well as the chairmen of County Councils and large Urban District Councils, were invited to form local committees to liaise with the WRC regarding the allocation, reception and maintenance of all refugees within their area.

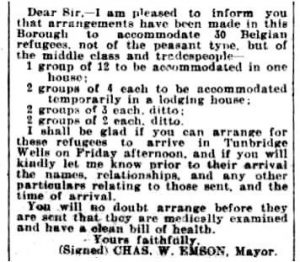

Letter from Mayor Emson to the Secretary of the Belgian War Relief Committee in Folkestone, published in both the Kent and Sussex Courier and the Tunbridge Wells Advertiser on Friday 16th October 1914 (Source: British Newspaper Archive)

The Mayor of Tunbridge Wells, Councillor Charles Whitbourn Emson, did just that, and chaired the Committee throughout the war, continuing with the role when he was replaced as Mayor in November 1917. The Committee worked tirelessly to make the refugees welcome, and by the end of October 1914 nearly 100 refugees had been placed in accommodation by the Committee. In total some 297 destitute people – 78 men, 144 women, 35 boys and 40 girls – found a safe haven here in Tunbridge Wells, though the most at any one time was 96 adults and 35 children. (This number was augmented by those who were able to support themselves or who stayed with friends.)

After the war, members of the Tunbridge Wells Refugees Committee, notably Councillor C.W. Emson and Amelia Scott, were decorated by the King and Queen of the Belgians in recognition of their work on behalf of the Belgian refugees in Tunbridge Wells.

The Mayor also opened a Local Fund for Belgian Refugees and in the months that followed, gifts of money, furniture and even homes, poured in, and lists appeared in the Courier each week of those who had contributed.

Some arrived with nothing, some did have some money and were able to support themselves, at least for the first few months; all needed clothing and basic necessities. Houses were rented and furnished, schools found for the children, English lessons given, a Belgian Shop opened on the High Street, and even a Belgian School in Spring 1918. Local doctors gave their services free of charge, and the Kosmos cinema and Opera House provided free entry to shows.

Tunbridge Wells Opera House today (© Alison Sandford MacKenzie 2016)

There were births, marriages, and deaths among the community, and St Augustine’s Catholic church was the scene of several high-profile funerals, as well as annual national celebrations.

The Belgians of Tunbridge Wells had their own Club, the “Club Albert”, and were given use of a room at the Constitutional Club on Calverley Road. Its Committee met regularly, hosted social events and information meetings for the Belgians of the district.

The newspapers published lists of refugees’ names to enable friends and families to discover their whereabouts – many families became separated as they fled, some were never reunited. The Mayor regularly used the pages of the Courier to ask for more help and funds for the refugee relief work.

As the war dragged on, refugees began to leave Tunbridge Wells, some went to the Front to fight, some moved to other districts to take up employment, others returned home, others moved on to France – a Belgian Repatriation Fund was set up as early as November 1915 – but many stayed until the war’s end, and when the Armistice was declared in November 1918, members of the Belgian colony joined the great celebratory parade wearing their Belgian colours of gold, red and black with what the Courier described as “smiling pride”, and bearing a banner declaring “Long live England. We thank you all.”

By the end of May 1919, when the Borough Refugees Committee met for the last time, all the Belgians had returned, most under the National Scheme by which free passage was provided by the British Government so long as they returned before 6th May 1919.

Postscript : Tunbridge Wells has an impressive souvenir of its First World War Belgian Colony – a life-size bronze bust of the Mayor, made by Belgian sculptor – himself a refugee – Paul Van den Kerckhove, and presented to the town by its guests in September 1915. It stands in the lobby to the Council Chamber in the Town Hall.

“This work (…) will be a public proof of our gratitude, a souvenir of the stirring times in which our countries have aided each other; and when (…) any of you cast your eyes on this gift, you will recall with gratification the signification of this bronze, and will give a thought to the exiles of today whom you comforted so greatly in the time of their distress.

“In the name of the Belgian Colony, and as a token of our gratitude, I present to the town of Tunbridge Wells the bust of its respected Mayor.”

Contemporary translation of speech by Belgian refugee, Professor Joseph Willems, in September 1915

[1] The exact number is uncertain – the Kent and Sussex Courier of 2nd October 1914 and The Tablet Catholic newspaper of 17th October 1914 both recorded that 24 people had arrived at Clayton’s, while the Tunbridge Wells Advertiser of 9th October 1914 reported that about 42 had been accommodated there – a salutary lesson not to believe everything in the newspapers!

SOURCES

- The Kent and Sussex Courier (British Newspaper Archive)

- The Tunbridge Wells Advertiser (Tunbridge Wells Library on microfilm)

- The Times Digital Archive

- The Tablet archive

- Belgian National Archives, Brussels : BE-A0510 / T 476 – Inventaire des archives du Comité officiel belge pour l’Angleterre (réfugiés belges en Angleterre), 1914-1919 / P.A. Tallier

- Alison Sandford MacKenzie, ‘Belgian Refugees in Tunbridge Wells’, in J. Cunningham (ed) The Shock of War, Royal Tunbridge Wells Civic Society, 2014.