Students on our Ancient History and Archaeology masters degrees in Rome have written blog posts as part of their assessments due as part of their studies. One student has shared her blog with us, read on to find out more about the Colosseum and its environs:

“As one of the most recognised buildings in Italy, the Colosseum is a well known symbol of the city of Rome, however not many people know the history of this great monument. Nestled in the valley between the Palatine, Esquiline, and Caelian hills1 at the head of the modern Via dei Fori Imperiali (fig 1),2 the Colosseum was used for public spectacles. Built by Vespasian, Titus and Domitian in the 1st century AD, it was an attempt to return the land taken by Nero to the people. This blog will discuss the history and construction of the Colosseum and the origin of its name.

In AD 64, during the reign of Nero, a fire swept through Rome, destroying much of the city.3 Nero took some of the land that had been razed and built the Domus Aurea, his Golden House,4 an expansive luxury complex that would become his imperial palace, which Suetonious describes in detail.5 The place was so large that Martial records that “a single house now stood in all the city.”6 After his suicide in AD 68, the city of Rome went through a period of civil war, the Year of the Four Emperors, until Vespasian secured his rule in AD 69.7 A few years later, in AD 70, Vespasian and his son Titus suppressed the Jewish revolt in Jerusaleum which had begun in AD 66, and returned to Rome in AD 71 to celebrate a joint triumph over the Jews,8 which is commemorated on the Arch of Titus.

Seeing the state of Rome, a damaged city  after the civil war10 and being dominated by the Domus Aurea, Vespasian sought to return the city of Rome from Nero to the people. This move was well within the Flavian approach, basing their rule on “returing to ‘popular’ and ‘Republican’ values.”11 They did this by draining and building the Flavian Amphitheatre12 on the site of the private pool that had been part of the Domus Aurea complex.13 A recently discovered inscription is thought to state that “the Emperor Vespasian ordered a new amphitheatre to be built from the booty [of the Jewish War]“,14 further enforcing their attempt to give back to the people by reinvesting the spoils of war into their needs. There is some debate over this inscription: all that survives are the dowel holes that secured the bronze letters in place. Hopkins and Beard express their scepticism on this as a “suspiciously appropriate solution to ‘joining the dots’.”15 It does seem to be a convenient solution, however with construction beginning in AD 7016 and following the years of the civil wars, surely the largest source of income for Vespasian to fund the Colosseum would have been what he could loot from Jeruasleum.

after the civil war10 and being dominated by the Domus Aurea, Vespasian sought to return the city of Rome from Nero to the people. This move was well within the Flavian approach, basing their rule on “returing to ‘popular’ and ‘Republican’ values.”11 They did this by draining and building the Flavian Amphitheatre12 on the site of the private pool that had been part of the Domus Aurea complex.13 A recently discovered inscription is thought to state that “the Emperor Vespasian ordered a new amphitheatre to be built from the booty [of the Jewish War]“,14 further enforcing their attempt to give back to the people by reinvesting the spoils of war into their needs. There is some debate over this inscription: all that survives are the dowel holes that secured the bronze letters in place. Hopkins and Beard express their scepticism on this as a “suspiciously appropriate solution to ‘joining the dots’.”15 It does seem to be a convenient solution, however with construction beginning in AD 7016 and following the years of the civil wars, surely the largest source of income for Vespasian to fund the Colosseum would have been what he could loot from Jeruasleum.

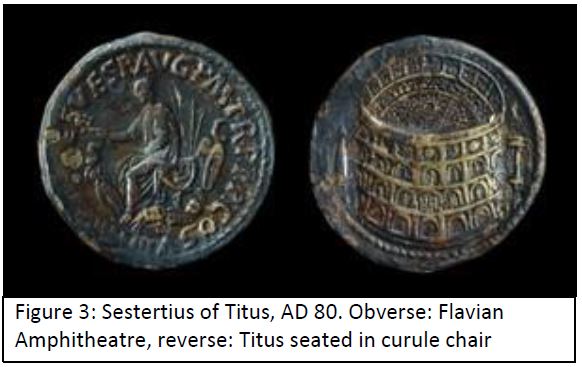

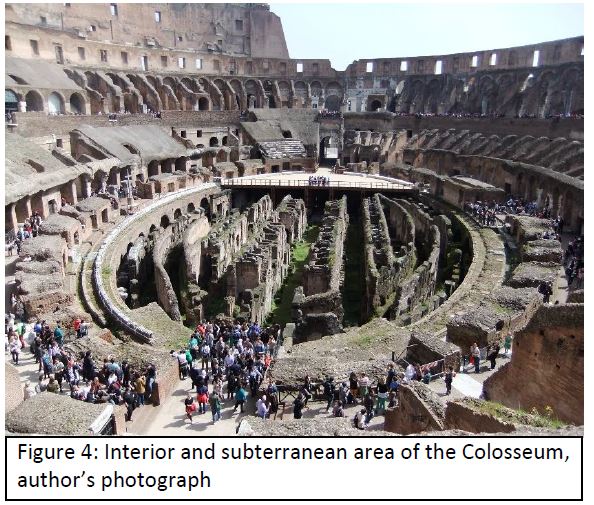

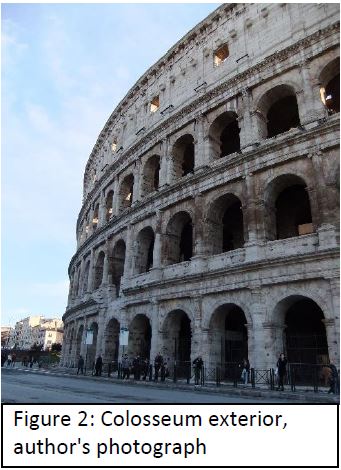

By AD 79, the Colosseum had reached its second level and was dedicated for the first time before Vespasian’s death that year. Titus continued the project and completed the aphitheatre up to the fourth level (fig 2) and rededicated the monument in AD 80 with lavish inaugural games.17 The dedication of the Colosseum is both recorded on coins of the time (fig 3),18 and in ancient accounts. Dio gives details of these events lasting for 100 days, which included beast hunts, group and single combat, the flooding of the arena for “sea battles”, and horse races. There were also distributions of largesse to the people.19 Titus also opened the baths of Titus to the public, which he had remodeled from the private baths of Nero.20 After this, Domitian is thought to have finished the exterior and installed the subterrainan area under the arena21 (fig 4), which would have been used to house animals and equipment used in the events.

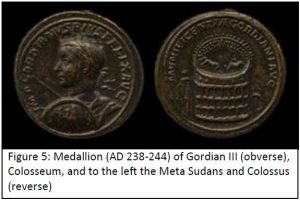

The name of the Colosseum also has its own history. While it has been known by many names, like Amphitheatum Flavium22 and the hunting theatre,23 the one which we call it today may owe its origins to Nero. Near to the Colosseum stood a colossal bronze statue of Nero. Pliny records that it was 110 Roman feet tall,24 around 32m, and is thought to have stood in the atrium of the Domus Aurea.25 However, after Nero’s death, because “of the public detestation of Nero’s crimes, this statue was consecrated to the Sun” by Vespasian.26 It had been moved closer to the Colosseum by Hadrian with the help of 24 elephants so that he could build his temple to Venus and Rome.27 On a medalian of Gordian III, the Colossus is depicted next to the Colosseum (fig 5)28 showing that it was still standing in the late empire and that it had become a marker of this area as much as the Colosseum and the Meta Sudans, a monumental fountain near the Colosseum, which is also depicted on the medallion. It is thought that at some point between the 8th and 11th centuries,29 the name Colosseum was first asscribed to the aphitheatre because of its proximity to the Colossus rather than its own colossal size.30

The work carried out by the Flavian emperors in the construction of the Colosseum took the private imperial luxuray that was the Domus Aurea and transformed it into a place of pleasure for the people.31 Their efforts to rework and develop the area attempted to remove the mark that Nero had left on the city of Rome but their efforts only go so far. To this day, the Colosseum is so called because of its proximity to the Colossus of Nero, while ascribed after the fall of the Empire, it is a strong reminder of Neros extravagance and the power of memory in history. “

1 Coarelli 2007:164.

2 Fig 1: Coarelli 2007:158, fig.43.

3 National Geographic 2014.

4 Coarelli 2000:9.

5 Suet.Nero.31.

6 Mart.Spec.2.

7 Hopkins & Beard 2005:26.

8 Hopkins & Beard 2005:26-7.

9 Platner 1929:45-47.

10 Hopkins & Beard 2005:28.

11 Coarelli 2000:10.

12 Britannica 2018.

13 Mart.Spec.2. Coarelli 2007:164.

14 Aicher 2004:181.

15 Hopkins & Beard 2005:33-4.

16 Hopkins & Beard 2005:36.

17 Coarelli 2007:164.

19 Dio.Rom Hist.66.25. See also Suet.Tit.7.

20 Coarelli 2000:10-11.

21 Coarelli 2007:164.

22 Benario 1981:256.

23 Hopkins & Beard 2005:21.

24 Pliny.NH.34.18.

25 Coarelli 2007:170.

26 Pliny.NH.34.18. Suet.Vesp.18.

27 Soprintendenza Archeologica di Roma 1997:8. (SAR)

28 Fig 5: BMCRM 13, p.48.

29 8th: Coarelli 2007:170. 11th: SAR 1997:8.

30 Hopkins & Beard 2005:34.

31 Hopkins & Beard 2005:31-2.