Professor Darren Griffin

In a time when the “double whammy” of Brexit and Covid-19 are having a catastrophic effect on University finances, we are pleased to report a success story coming out of Biosciences that originally arose as a result of a student project. Back in 2011, Darren Griffin set Becky O’Connor the task of developing a screening test that could detect infertility in pigs. A prototype formed part of her MSc, a fully-fledged version part of her PhD and it has now developed into a multi-national operation that supports two salaries and several PhD projects.

Factoring in bacon, sausages, pork chops and the like, our humble domestic pig provides 43% of meat consumed in the world. Pigs are thus the leading source of meat protein globally and the most environmentally efficient way to get as much meat per body weight from any one animal. In most developed countries, commercial pig breeding operates like a pyramid. At the top are our “super boars” selected on their genetic merit (meat quality for instance is an indicator). These chaps can be asked to inseminate over 1,000 sows in their lifetime – by artificial insemination in case you were wondering. Typically, they have about 11,000 children (the next tier down in the pyramid) who are inter-bred to produce the meat we see in our supermarket (this is the pyramid base).

For this, the fertility of these “super boars” is paramount as it can have profound effect on litter sizes of the children (25-50% lower) and, because it is a genetic trait, grandchildren, great grandchildren and so on. Infertile boars lead to reduction in food production and higher environmental costs as unproductive males can cause unnecessary greenhouse gas emissions. When a fertility issue exists, it is usually caused by a so called “chromosome rearrangement” – the reciprocal exchange or ‘translocation’ of parts of the genome.

The potential financial and environmental costs of using an infertile boar in a breeding pyramid are enormous. The need therefore to identify these infertile animals is paramount, particularly as pig semen from these boars (because of the quality of its genetics) is a major export for the UK economy.

To cut a very long story short, 9 years on, the test developed in Biosciences is now the “industry standard” for most European commercial pig breeders. With 15 customers in 10 European countries, 1,800 samples screened and 80+ infertile boars found, we are now reaching out to USA, Australia and Thailand with considerable success. Pig breeding is a major, and growing, industry in South East Asia and our goals here are to support local teams in their improvement of the security and resilience of the local pig breeding industry. Our method will support initiatives in Thailand to improve the genetic quality of their breeding stock, thereby ensuring long term market growth and reducing the financial and environmental risks associated with excess waste. The emphasis will be on generating high-quality meat products, bred under first-class welfare and environmental conditions.

All of this activity falls under the banner of an activity we call “CytoScreen Solutions” and we are developing a similar test for cattle. “Super bulls” are therefore the next on our list as are new tests for DNA damage in sperm as well as hands-on training courses in the Middle East. Far more than just a routine service however this activity underpins and helps to fund basic research activity, and has contributed greatly to numerous publications, PhD chapters, and a leading impact case for REF2021.

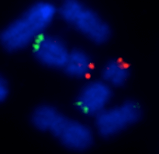

Normal boar chromosomes highlighted using the CytoScreen method. Each chromosome is brightly lit in red on one end and green on the other

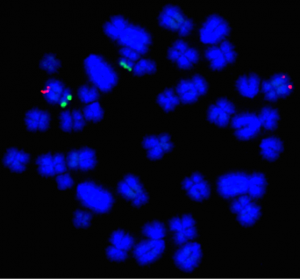

An abnormality identified using the CytoScreen method. It is easy to spot as one set of signals are split across different chromosomes

As well as Becky (now the University’s only Research and Business Development Fellow), the team that have worked on this project include Lisa Bosman (a current PhD student) as well as postdocs Claudia Rathje, Lucas Kiazim and Becca Jennings. With eight University of Kent degrees between them, they collectively have accrued over 35 years’ service to the University. Lucas Kiazim said “this project has given me a range of opportunities over and above what is normally on offer for a PhD student. These include travel to, and organising conferences, interaction with industry, commercial awareness, extra publications, not to mention much needed funding.”

With the University’s support, we hope to develop and grow this flagship enterprise activity that ticks all the boxes for impact led research activity. Our next challenge will be to get the lab up and running post Covid-19 lockdown. In these difficult financial times, something that is actually generating income, as well as helping to feed people in an environmentally sustainable way, can only be good news.

- O’Connor, R. E. et al. Isolation of subtelomeric sequences of porcine chromosomes for translocation screening reveals errors in the pig genome assembly. Genet. 48, (2017).

- Darren Griffin and Rebecca O’Connor. Screening for Reduced Fertility in Pigs: Bright New Ideas. Open Access Government, December 2019.

- Jennings RL, Griffin DK, O’Connor RE. A new Approach for Accurate Detection of Chromosome Rearrangements That Affect Fertility in Cattle. Animals (Basel). 2020 Jan 10;10(1):114.

- Darren Griffin Becky O’Connor, Giuseppe Silvestri and Lucas Kiazim. Improving cattle production by counting chromosomes. Open Access Government. January 2020