During elections, pandemics, and when important social and political events occur, people often turn to conspiracy theories to explain what is happening. Professor Karen Douglas explains why conspiracy theories appeal to so many people.

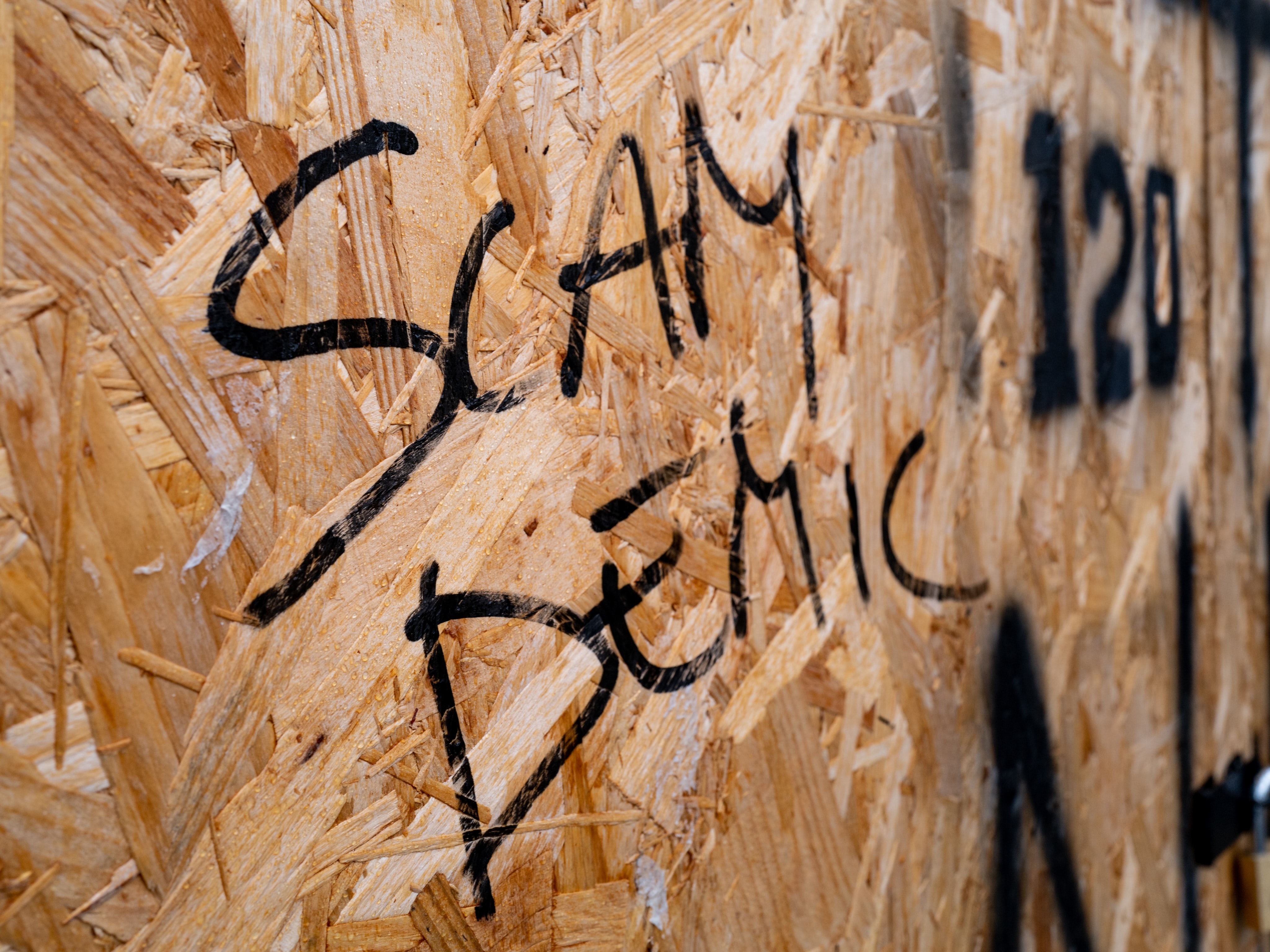

‘Almost immediately after the news started to emerge about Covid-19, so did the conspiracy theories. Some people claimed that the virus was deliberately leaked from a laboratory in Wuhan. Others argued that 5G technology spread the virus. When vaccines became available, some people claimed that they contained tiny microchips designed to monitor the population. Conspiracy theories—explanations for significant events and circumstances that implicate secret and malevolent groups with sinister goals—are common in times of crisis and unrest. But why do people believe in them?

‘Research suggests that people are drawn to conspiracy theories when one or more psychological needs are frustrated. The first of these needs are epistemic, related to the need to know the truth and have clarity and certainty. The other needs are existential, which are related to the need to feel safe, secure, and to have some control over things that are happening around us, and social, which are related to the need to maintain high self-esteem and feel positive about the social groups that we belong to.

‘In times of crisis and uncertainty, these psychological needs are likely to be particularly frustrated. People feel uncertain, out of control, threatened, and are looking for ways to cope with difficult circumstances. Conspiracy theories might seem to offer some relief. For example, conspiracy theories might promise to reduce uncertainty because they provide a simple explanation for a complex event. They might promise to give back a feeling of control, or make people feel better about themselves because they know things that other people do not know.

‘However, there is little evidence that believing in conspiracy theories does make people feel better. If anything, conspiracy theories appear to make people feel worse. For example, after reading about conspiracy theories, people tend to feel less powerful and experience higher levels of uncertainty. Believing in and spending a lot of time reading about conspiracy theories may therefore not alleviate people’s feelings of frustration, and instead make them feel more frustrated.

‘Conspiracy theories can affect people’s attitudes, intentions and behaviours. Historically, they have been linked with prejudice, genocide, risky health behaviour, climate denial, and political violence.’

Professor Karen Douglas’ research focuses on the antecedents and consequences of conspiracy theories.