One thing I do regularly, and enjoy, is give talks to companies about global politics. Today, I gave a talk in London to a major conference of financial investors who wanted to explore the current and future direction of British politics. So, I took the opportunity to set out why, in my view, the country is now rapidly heading toward a Labour government before we talked in more detail about what this means for economic policy, tax and wealth. Here are just ten of the slides from the much larger deck I shared with the conference and which I wanted to share with you. If you cannot see the slides just click ‘download images’ on your e-mail. And if you’d like me to speak at an event just drop me a note.

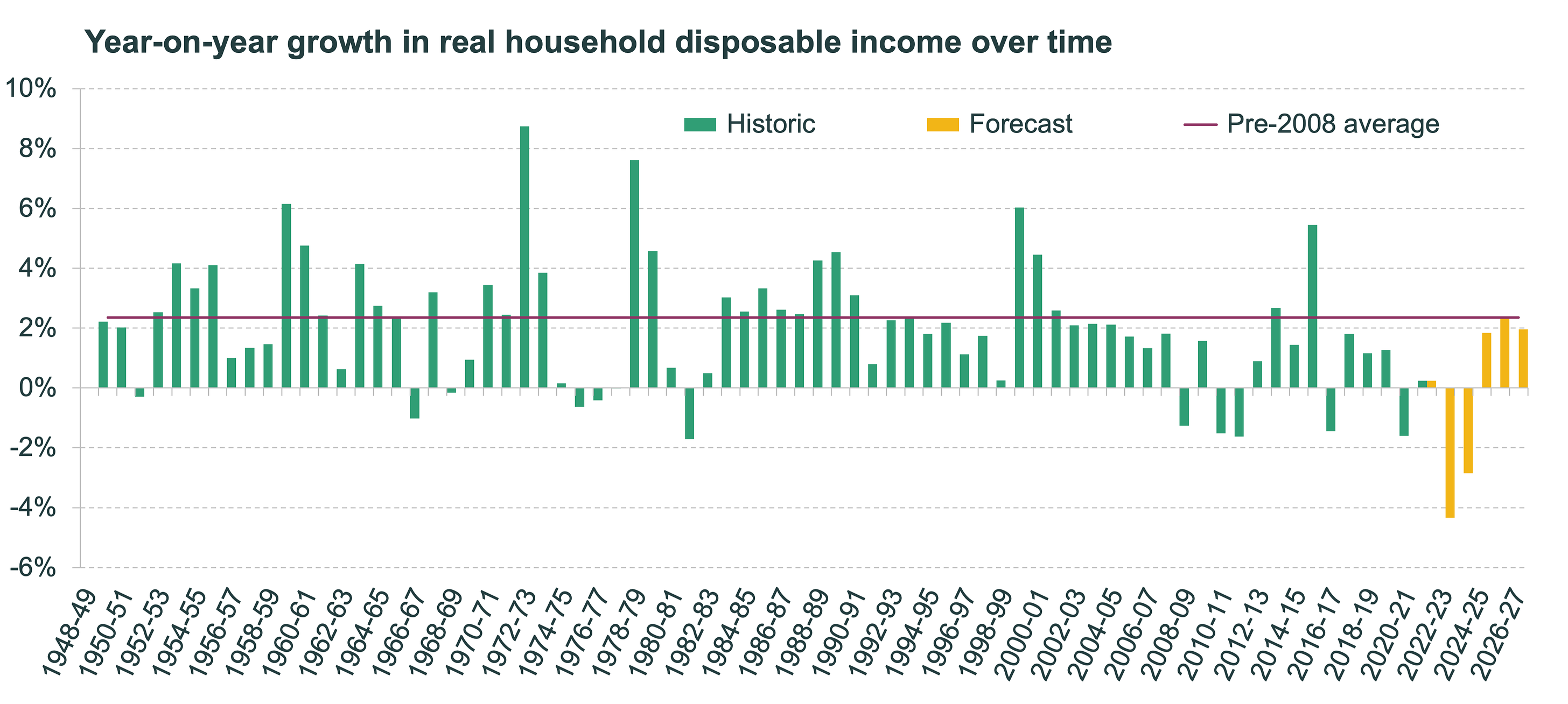

1. A Sustained Squeeze. The first thing to say is that Britain is on the cusp of an entirely new economic era, one that will be defined by a bigger state, higher rates of tax, low growth and a much more pronounced squeeze on living standards than anything we have seen throughout the entire postwar era. Recent estimates, from the Institute for Fiscal Studies, suggest that over the next two years household incomes, already weak since the financial crisis, will fall by around 7 per cent, the sharpest fall since the 1940s. The average household will likely not return to the standard of living they had last year until the late 2020s. The roaring twenties are now making way for a lost decade. The British people will also feel this sustained squeeze in a more direct way than previous crises, through higher mortgage bills, higher income tax, higher local council bills and significantly higher energy bills. And this will have significant political effects down the line. No prime minister who has ever presided over a major financial crisis, pressure on sterling or this kind of sustained squeeze has gone on to win the next election. Furthermore, at most of the elections that have taken place around the world since the rise of inflation and the energy crisis most incumbents have lost power or been severely weakened —as in America, Brazil, Columbia, France, Italy, Slovenia, South Korea, Sri Lanka, Sweden and the previous Truss government in the UK. This is consistent with studies on the impact of unexpected inflation, which have shown that between the long period of 1970 until 1994, for every unexpected one point increase in inflation there was a one point fall in support for the incumbent party.

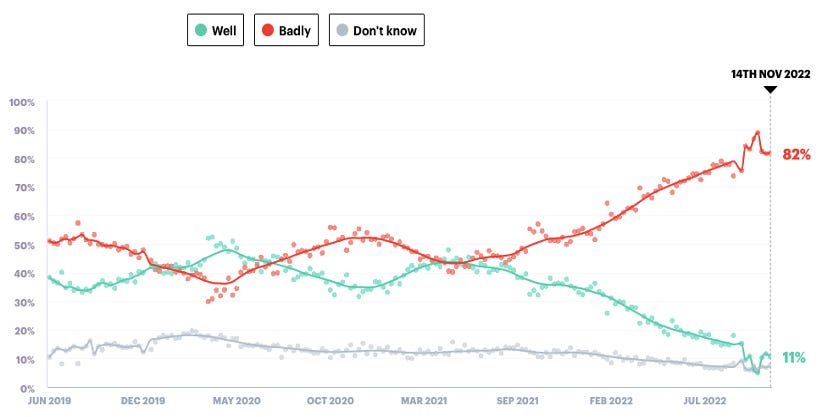

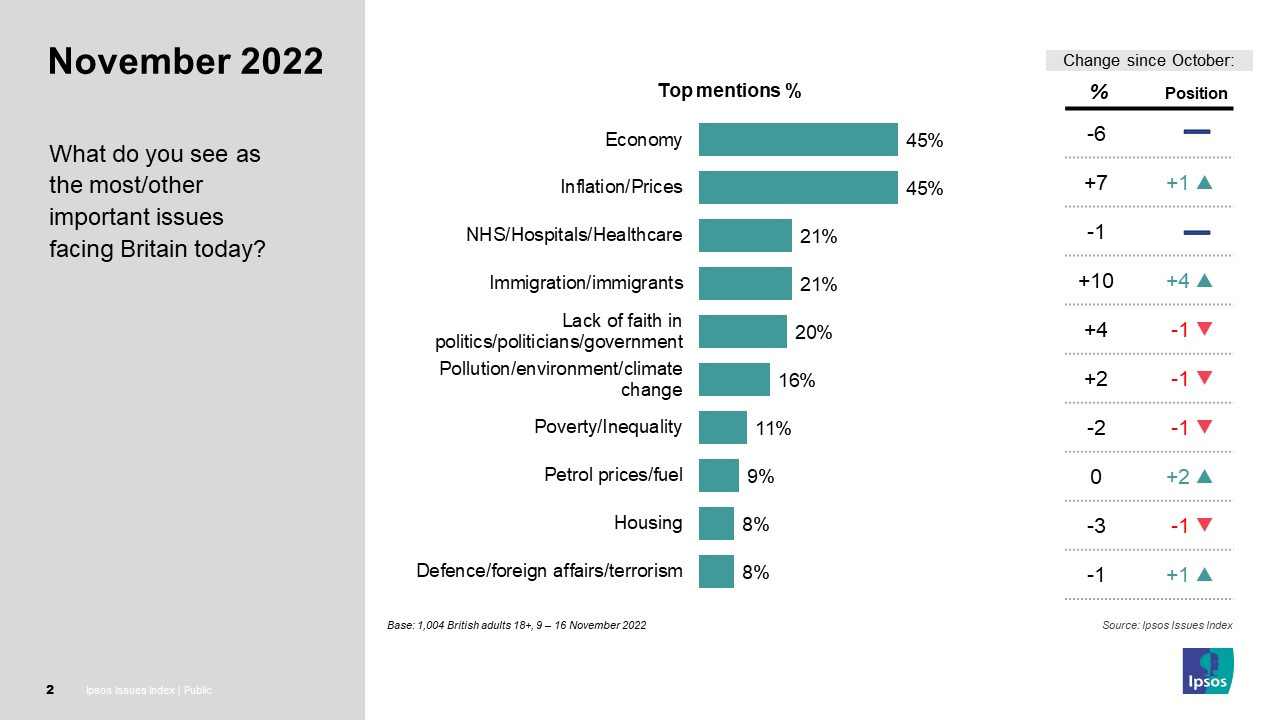

2. Economic Competence. Amid this climate, the biggest problem of all facing the Conservative Party is they are no longer trusted by much of the country on the economy —which is now, by far, the most important issue for voters. When it comes to this issue the average voter feels fed up, deeply anxious and very pessimistic, displaying levels of economic pessimism we have not seen since the eruption of the global financial crisis in 2007-2008. They are also scathing of the Conservative Party on this issue. The share who say the government is managing the economy “badly” has spiralled to 82 per cent while only 11 per cent of the country think the government is managing it “well”. Even more worryingly for the Conservatives, this widespread disillusionment is just as visible among their own voters —70% of Conservative voters now say the Conservative government is managing the economy “badly”. And most voters blame the Conservative government, not global winds, energy firms or Brexit, for their current economic difficulties. When voters were asked this week who they blamed for the sharp rise in interest rates 45 per cent pointed to “the British government’s management of the economy” while only 23 per cent pointed to “the global situation” and 8 per cent each to “the war in Ukraine” and “the legacy of Covid-19” (Brexit was a distant fourth). Incumbent parties with these kinds of numbers on the most important issue for voters simply do not win elections.

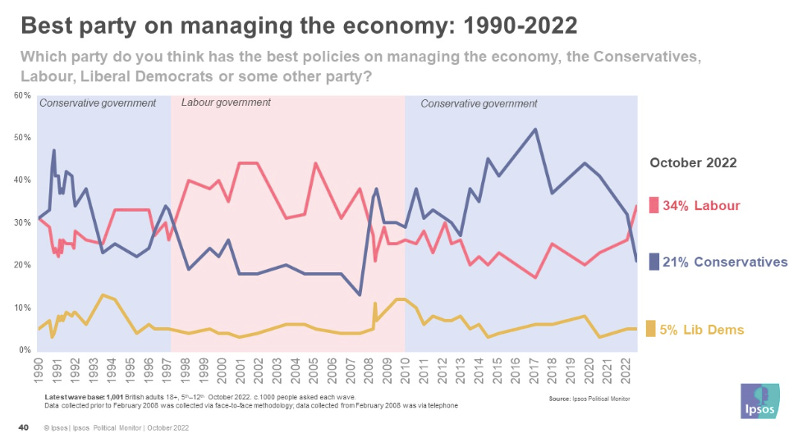

4. Issue Ownership. The Conservative Party is not just distrusted to manage the economy; it has also lost ownership of this crunch issue. Typically, parties which ‘own’ the most salient issues tend to win elections. Margaret Thatcher owned inflation, strikes and unemployment. Tony Blair owned the National Health Service and education. David Cameron owned the economy, immigration and drew level with Labour on education. But today, for the first time in fifteen years, the Conservatives have lost ownership of the economy. Despite saying little at all about their long-term strategy, Sir Keir Starmer and the Labour Party are now seen as the best party on the economy. In my own polling, when we ask people who they think would be best to manage the economy, 30% say “a Labour government led by Sir Keir Starmer” while only 17% say “a Conservative government led by Rishi Sunak” (though note a very large number now say “none of them”). Remarkably, only a minority of Conservative voters back their own party to manage the national economy, while large numbers now say “I don’t know who to back”. Here is the longer-term trend which underlines how the tide has now firmly turned against the incumbent Conservatives …

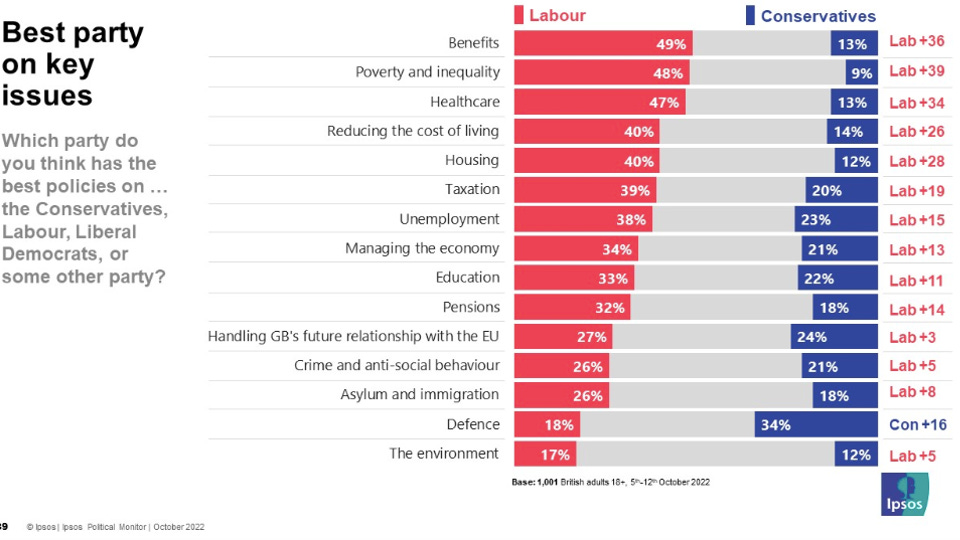

5. The Wider Agenda. And it’s not only the economy. On almost every issue in British politics today —benefits, poverty, healthcare, the cost of living, housing, tax, unemployment, education, pensions and the environment- it is the opposition Labour Party that now holds statistically significant if not very large leads over the incumbent Conservatives. In fact, in some polls the only issue on which the Conservatives lead is defence which, despite the war in Ukraine, is not a very salient issue. So weak are the Conservatives, so adrift from the country, that even on their core issue of Brexit they are no longer ahead. Let me put that another way —the party that campaigned for a second referendum to overturn Brexit is now seen as the preferred party to manage Brexit. And when you ask Leavers who they back on Brexit, the very voters who were key to Boris Johnson’s victory in 2019, a larger number of them now say “I don’t know who to back”, “none of them” or “some other party” than the number who back the Conservatives. Given that the Conservative Party have now completely redefined themselves around the Brexit question this is another dangerous place for the party to be.

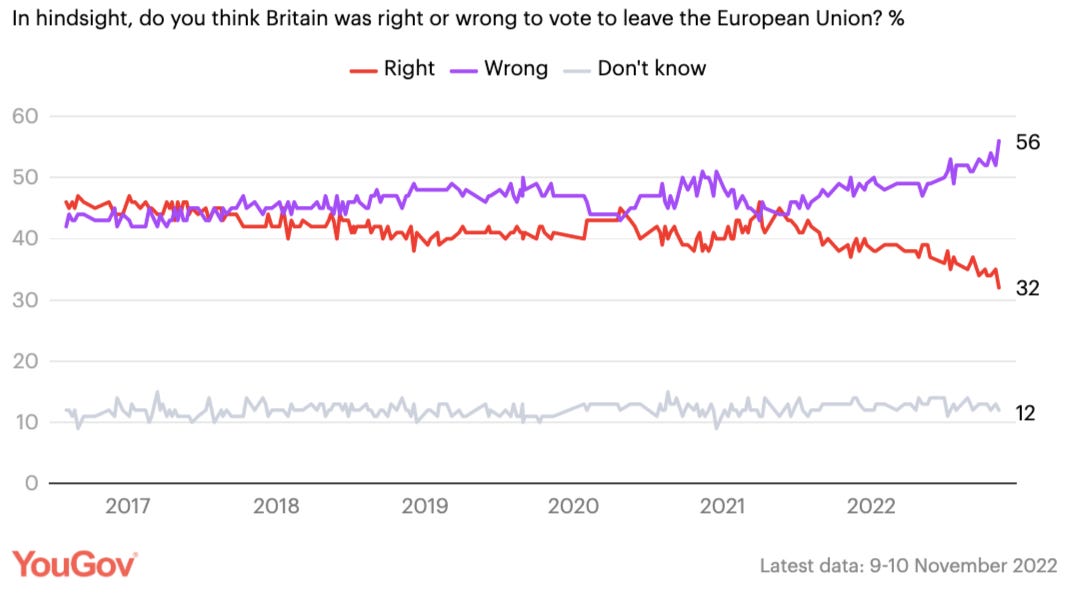

5. Intensifying Bregret. This is also problematic for Rishi Sunak and his party when you step back and look at the wider trend in how people think about Brexit. As I wrote back in the summer, long before others were pointing to it, regret over the vote for Brexit, or “Bregret”, is rapidly becoming a key feature of British politics. Whatever your personal view, whether you were for Brexit or against it, the political reality is that the share of voters who now feel that in hindsight Brexit was the wrong decision has been steadily climbing to a record high of 56 per cent while the number who think it was the right call has fallen to just 32 per cent. If I am right, and Brexit continues to become intimately associated in the minds of voters with an escalating economic downturn and prolonged squeeze on living standards then the Conservatives will increasingly find themselves in a vulnerable place —in a world where majorities of every age group below pensioners, where nearly two-thirds of young 18-24 year old Zoomers from Generation-Z, who are increasingly entering the electorate, and where one in every five Leavers now think Leaving the EU was the wrong call. The more public enthusiasm for Brexit drains away, the harder life becomes for the pro-Brexit Conservatives.

6. Immigration Scepticism. Brexit was always crucial for the Conservatives in 2017 and 2019 because it raised the salience of the ‘cultural dimension’ of politics, cutting across the traditional left-right divide and helping the party to reach into economically left-wing but culturally conservative Labour voters. Another issue that does this is immigration, with large numbers of voters feeling deeply concerned about both the pace and scale of migration. This is why the perceived importance of the issue has also been rising. It is now the joint third issue for all voters and the second top issue for Conservatives. But here again, Rishi Sunak and the Conservatives are in serious trouble. What should be another key issue for a conservative party is one on which the vast majority of voters no longer trust the Tories and think they are doing a bad job. In fact, 82% of all voters and 85% of Conservative voters now say the government is handling immigration “badly” while just one in ten of voters think they are doing a good job. And this also applies to the small boats —as I have written previously, the vast majority of voters simply do not believe the Conservative Party is controlling Britain’s borders. And, after everything, after Rwanda, the deal with the French and all the tough talk from Suella Braverman, today only 5% (!) of the country think the government has a plan to deal with the small boats in the channel.

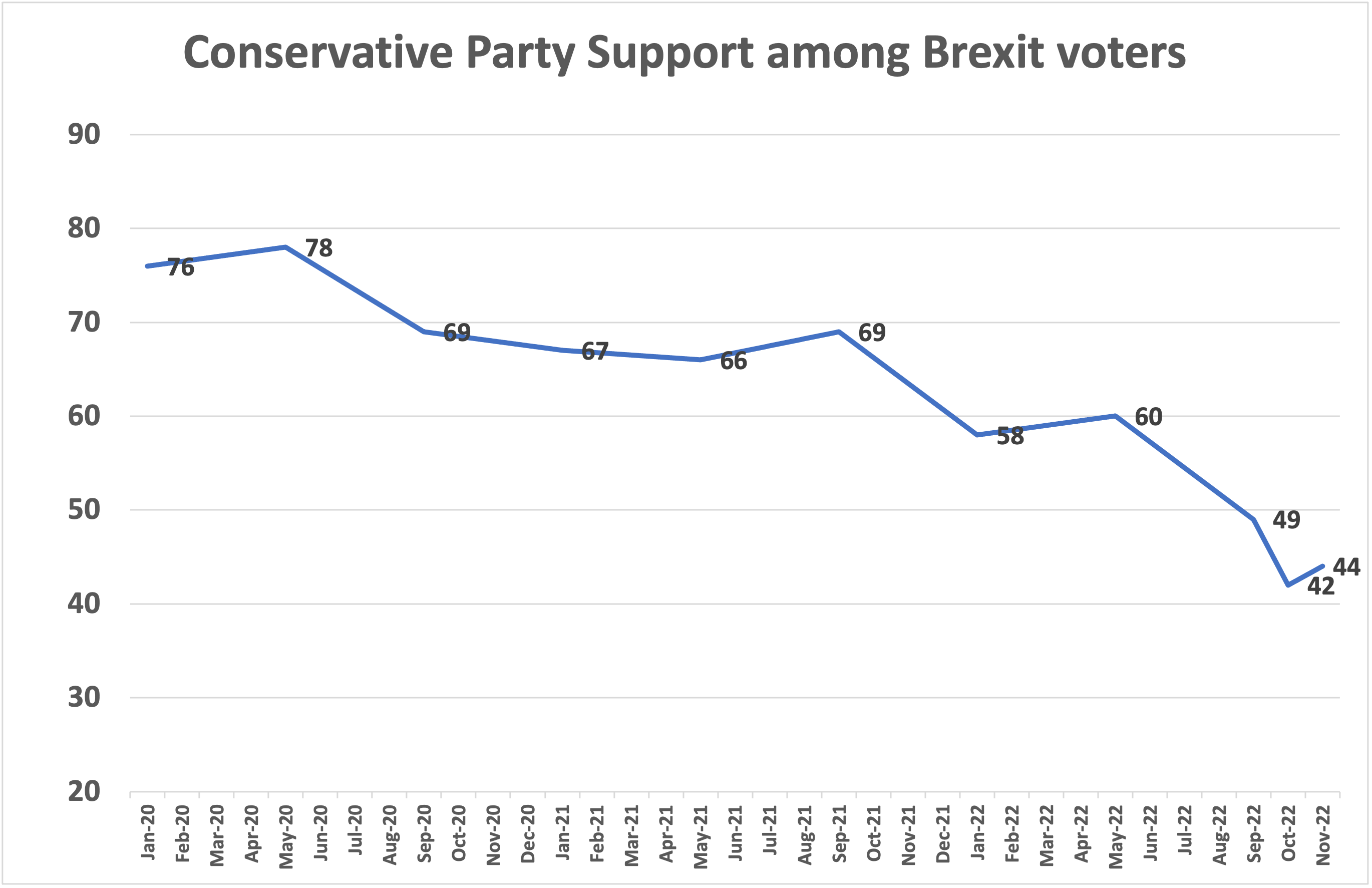

7. Lost Leavers. These trends help to explain the Conservative Party’s catastrophic loss of support among Leave voters, the very people who voted for Brexit and then Boris Johnson in 2019, who were key to the post-Brexit realignment. Since the 2019 election, the share of Leavers who plan to vote Conservative at the next election has cratered by more than thirty percentage points, from 76 per cent to just 44 per cent today. This trend not only reflects their disillusionment over how Brexit and other closely-related issues, notably immigration, have been handled but underlines how, unless things change, Sunak and his party will find themselves being chased out of the many pro-Brexit, working-class and older seats which were central to the party’s emphatic victory less than three years ago. The only way forward for the party at the next election was to lean into the realignment of British politics, to double down on and expand the seats it won in Brexit Country in 2019 while trying to minimise losses in Remainia. But instead the party tried to be all things to all voters while managing its core issues very badly and so, in turn, is now haemorrhaging support on both flanks.

8. Dishy Rishi? Leadership ratings also matter. And if you look at the ratings of recent Conservative Prime Ministers they were absolutely dire. Both Boris Johnson and Liz Truss collapsed to historic lows and inflicted serious damage on the Conservative brand along the way. Today, Rishi Sunak also remains in “net negative” territory, with a rating of minus 8. The good news for Sunak is that he is far more popular than his party and more popular than his two predecessors. The bad news for Sunak is that the party he is leading is incredibly unpopular, with a net satisfaction rating of minus 60 which is basically where it was under Truss and Johnson. Sunak has inherited a poisoned chalice, in other words, a deeply damaged brand in politics that he will struggle to turn around with only twenty-four months to go. He is also deeply vulnerable on his right-wing flank. Many cultural conservatives simply do not believe he is serious about taking control of immigration and the borders, an issue that has been stoked by the news this week that overall net migration has now surged to a postwar high of 504,000.

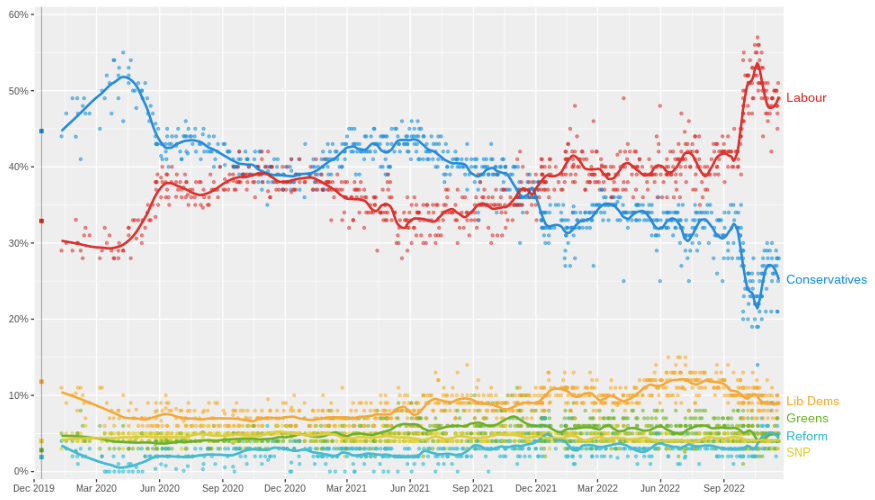

9. The Polling Trend. Which brings me to the wider trend. Over the last year, the Conservative Party suffered two big hits in the national polls. The first was Partygate, in late 2021. The second was Trussonomics, in late 2022. Both events have inflicted significant damage on the party, costing it close to twenty points in the polls (though Truss inflicted far more damage than Johnson). This week, the Conservatives are still only averaging 24.6 per cent while Labour is averaging 48 per cent, a 23-point lead for Sir Keir Starmer and the Labour Party. Were these results replicated at a general election they would likely deliver a Labour majority of nearly 300 seats and leave fewer than 100 Conservative MPs in the Commons. We should certainly treat midterm polls with a pinch of salt, not least given the fact that more than one in three 2019 Conservative voters currently say they would not vote, do not know who to vote for or would switch to the insurgent Reform party, which has now pledged to stand a candidate in every seat at the next election. Sunak will be hoping that many of these voters “come home” but this may well be downplaying the extent to which, as we have seen, these voters have become deeply disillusioned with the Conservative Party and no longer seem to believe that the party knows what it believes or has a sense of clear purpose.

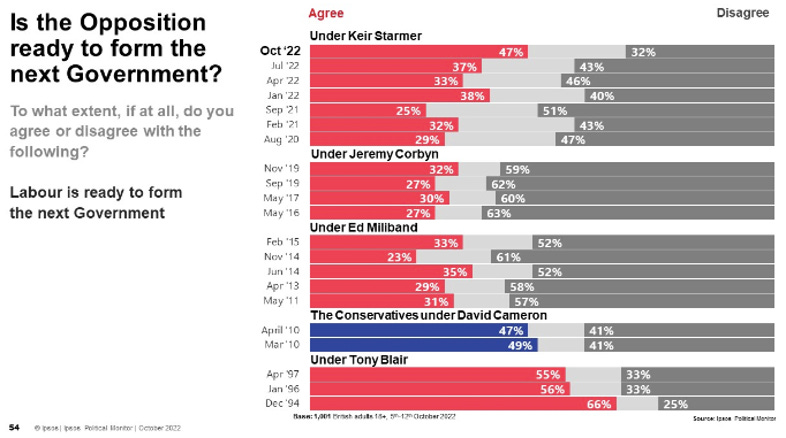

10. Expectations. Lastly, there is one other metric which I do think is important and few people have picked up on. And it relates to the public image of the opposition Labour Party, a party that for much of the last decade struggled to project itself as a credible, coherent and compelling alternative. But that too is now changing. According to a regular tracker, by Ipsos-MORI, nearly half the country, 47 per cent, now think the Opposition is ready to form the next government. To put this figure in perspective, it is the highest for any opposition party since David Cameron and the Conservatives prepared for government in 2010 and is the highest figure for any Labour Opposition since Tony Blair and New Labour prepared for government all the way back in April 1997. Neither Ed Miliband nor Jeremy Corbyn ever came close to the current figure. There is no doubt the Labour brand is still in recovery and Sir Keir Starmer’s ratings are nowhere near as strong as Tony Blair’s once were. But it is also true that against the backdrop of a very unpopular incumbent Conservative government the numbers of voters who think the Labour Party cares about ordinary people, is a moderate rather than extreme party and is a competent party and a united party have been rising. This, alongside everything else we have discussed, is yet more evidence for why, unless things change, Britain is not only heading toward a Labour government but most likely one with a very significant majority. Thanks for listening.

This is repurposed from Professor Matt Goodwin‘s Substack, you can subscribe here.