Stephen Chambers describes his paintings after William Blake as ‘reverential love letters’ to an artist who was the ‘gate-master of the misfits’ club’. While Blake inspires devotion in people from all walks of life, he is – like David Bowie – an artist that each admirer feels that they are engaged in a personal conversation with. An artist that it seems they are the only ones to know about. Perhaps this is why these works by Chambers have occasionally provoked criticism: ‘this is not the Blake I know… the true Blake!’ Yet Blake’s oeuvre demonstrates within itself a rich potential for reinterpretation, with multiples and even motifs (like The Traveller or Death’s Door) being reworked over time and re-contextualized. The hand-colouring of prints, for example, varies greatly, whether carried out by Blake himself or his wife Catherine. An implicit permission is given, therefore, to test the images in order to discover what is essential and enduring, and what is more discrete and particular to a given iteration. Working, as he did, principally from black and white photographs of Blake’s works, Chambers was able to range freely as a colourist. The effect of his ‘incongruous’ colours is to dislocate Blake’s enigmatic images from an eighteenth-century aesthetic, and also from the comfortable embrace of biographical anecdote, and to make them strange and vital again. Blake did this too, whether he was working from the Laocoön, or the clumsy drawings of his brother Robert. What mattered to him was not the suave accomplishment of the academy and commercial print market, but a certain truth to feeling that snagged in the mind and continued to resonate in memory. In this sense, Chambers’ recreations are profoundly respectful to Blake’s original vision.

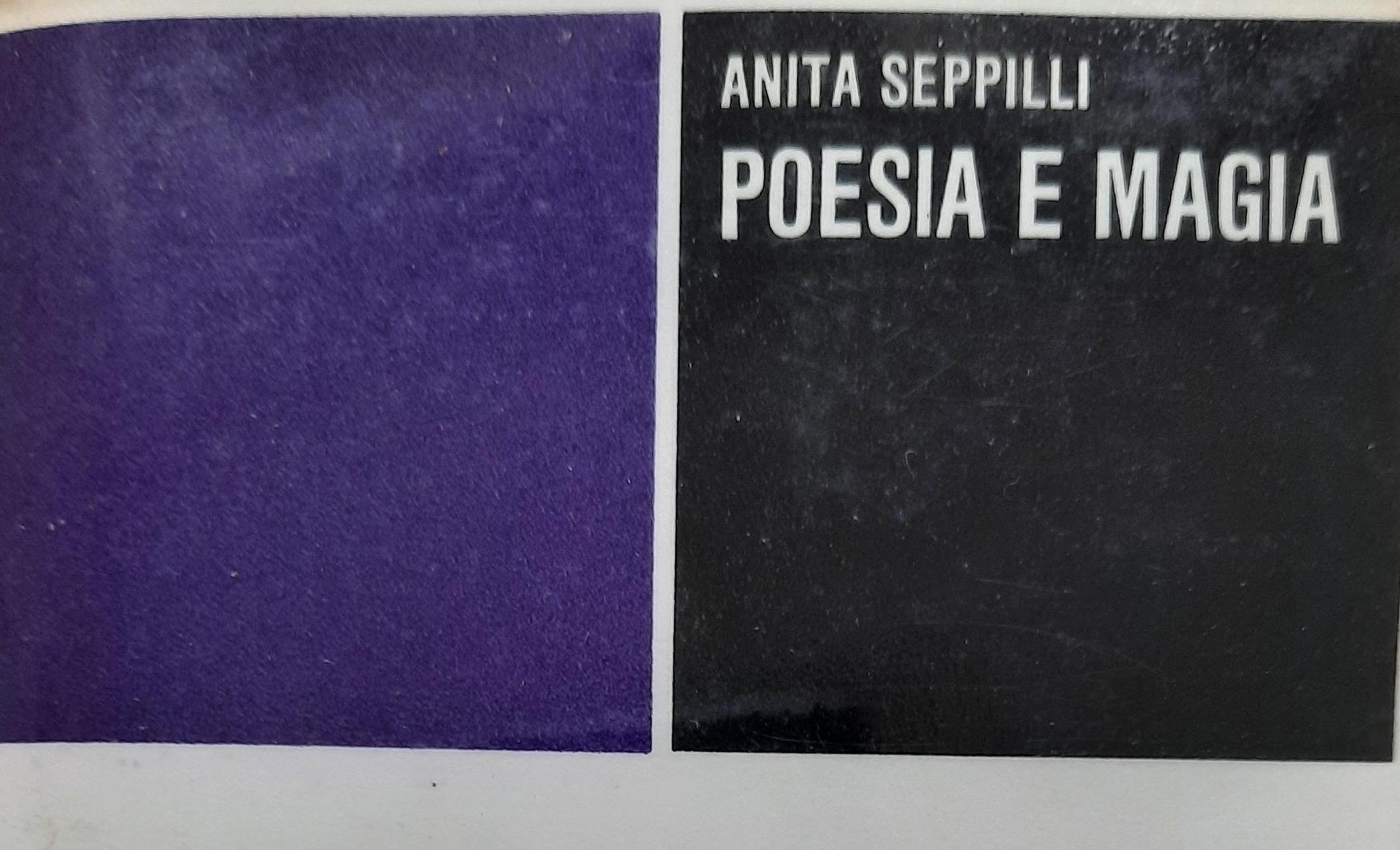

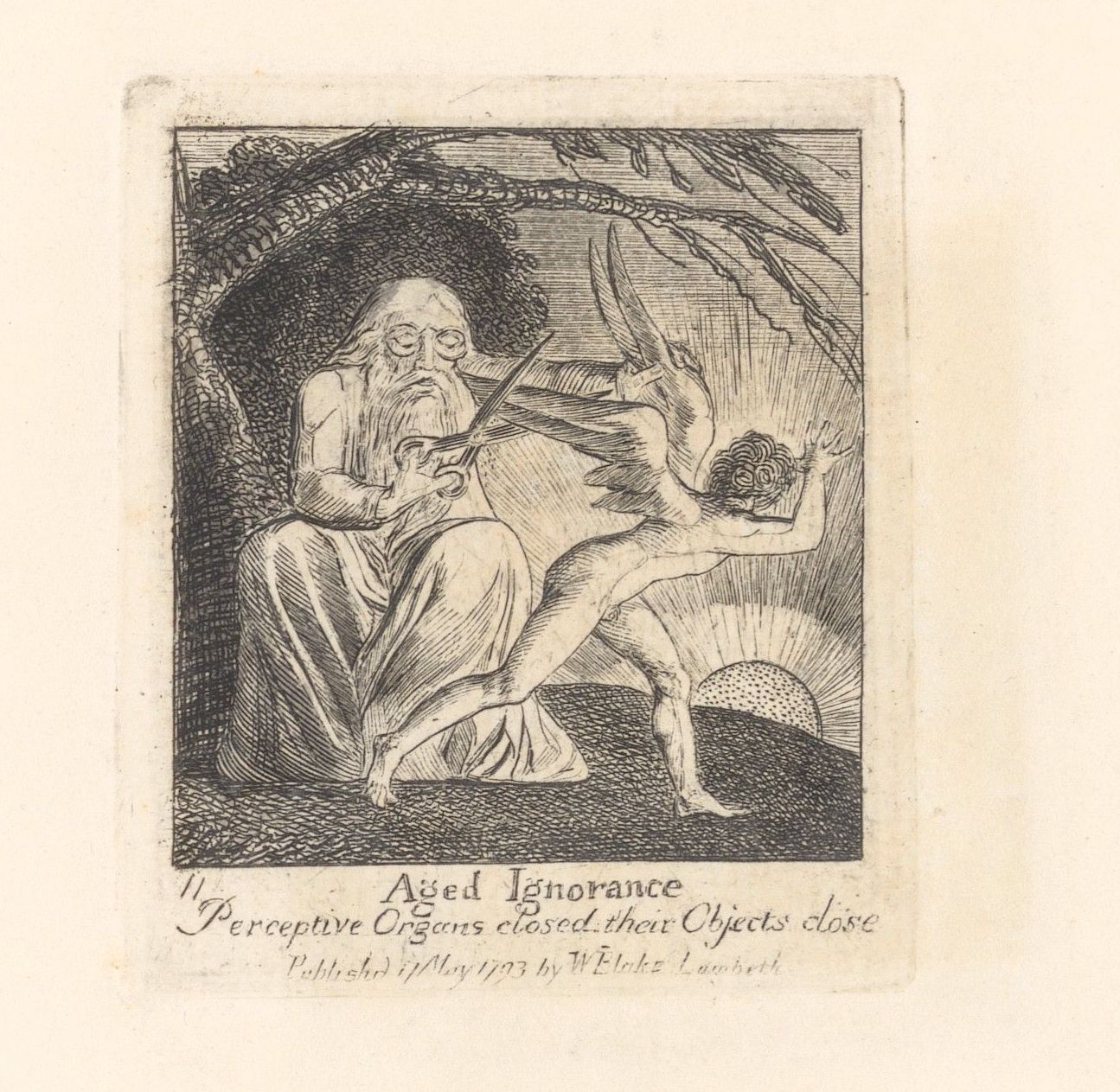

The four paintings by Stephen Chambers included in Poetry & Magic – Harvest, Sword, Scissors, and Two Black Angels,all from 2006 – are based on prints in Blake’s The Gates of Paradise (1793) and Songs of Innocence and Experience(1794). Harvest, in which a determined woman plucks human heads, like mandrakes, from the ground by moonlight at the roots of a tree whose twigs appear to ‘drip’ downwards, is based on Blake’s ‘I found him beneath a tree’, the first of a sequence of curious images in The Gates of Paradise (according to the numbering that Blake provided in his own poetic ‘key’ to their meaning). Chambers has added a slice of moon seen through branches in a green sky, some red flowers, and an open cardboard box for the heads. Sword has as its point of departure Blake’s eighth emblem, ‘My Son! My Son!’. Here an old man laments the fact that he is being treated by his child precisely according to the values with which he was raised: ‘My Son! my Son! thou treatest me / But as I have instructed thee’. In addition to the stylized tree, green sky and red flowers, Chambers has reworked the architecture of the throne on which the old man sits as brightly coloured and striped blocks, while also rendering the figures flat and featureless like silhouettes, the father painted red-brown and the son black. Scissors shows a pink-spotted man, sitting beneath the tree from Harvest, clipping the wings of a black angel who tries to flee towards the setting sun. This painting reworks the eleventh image in The Gates of Paradise: ‘Aged Ignorance. Perceptive Organs closed, their Objects close’. In Blake’s poetic key he wrote of this image: ‘Holy and cold I clipd the Wings / Of all Sublunary Things’. The spots that cover the aged man wielding the scissors seem to have migrated in Chambers’ painting from the stippling on the sun in Blake’s engraving. The Gates of Paradise is a book of emblems that distils into striking images a mystical vision of a spiritual journey through life. One in which a worldly conception of religion is rejected as Satanic (‘Truly My Satan thou art but a Dunce’). It is a condensed Pilgrim’s Progress. As Chambers puts it, Blake’s prints are ‘trying to make logical, the illogical’.

Two Black Angels, the freest of Chambers’ interpretations exhibited in Poetry & Magic, is based on plate 28 from Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Experience (1794). This image works as a pair with Blake’s frontispiece of a piping shepherd looking up at a sprite-like child (for inspiration), book-ending the section of the Songs of Innocence. Blake’s introductory poem makes clear the transition from piping, to song, to writing poetry with a ‘rural pen’ made from a ‘hollow reed’. In plate 28 the poetic shepherd holds the winged child aloft and triumphant, seated on his head, having presumably been inspired. The pose is reminiscent of the figure of Christ as the Good Shepherd, which itself derives from the Ram-Bearer, or Hermes Kriophoros (another comparable figure from antiquity is the Moscophoros, or Calf-Bearer, of the Acropolis, c. 570 B.C.). As with the paintings based on The Gates of Paradise, Chambers needed to adapt Blake’s ‘portrait’ formats in his prints to the ‘landscape’ orientation required by the shape of the moulded mahogany panels on which he worked. This prompted the inclusion of an additional black angel flying through the air, a dog sitting among red flowers who is watching two sheep, a sun in a green sky, and, notably, an additional tree, to the right, through the bare branches of which the shepherd figure holding a black angel on his head is glimpsed. It should be added that this comparative analysis of work and source might be illuminating for the artist’s creative process, but it is not a necessary initiation for the viewer of the painting. As Chambers puts it, these are ‘works that look after themselves’.

Chambers began this series of Blake Paintings with a work commissioned for a William Blake anniversary exhibition at Tate Britain. Having begun the process of interpreting prints by Blake, the artist continued, enjoying working in series and with subject matter that had been gifted to him. The use of wood panels as a support was also a significant development. Initially, as is the case with the works in Poetry & Magic, they were painted on the panels removed from a wardrobe that had been abandoned in an alleyway near Chambers’ Hackney studio. Once those had run out, the mouldings were recreated on subsequent wood panels. Working on a surface with flaws, and which is not flat, proved intriguing, complicating the journey from brain to mark, and forging a handwriting, an identity, in the making. The scale of the panels and their portability also opened up new paths, from the distillation of narrative required by the size of a work where ‘you see everything in one go’, to a more transitory artistic existence afforded by the ‘transportable scale’ of the works. For an artist who worried, while he was a student at St. Martin’s, that he had already ‘missed the groovy train’, these were important developments that challenged the ‘bigger is better’ aesthetic of the 1980s.

The Blake Paintings also made concrete thoughts that Chambers had been considering following student trips to Italy where he had encountered the Christian art of the Middle Ages and Renaissance, noticing the differing quality of artistic treatments of the same, repeated stories. Subsequent series, such as the 12 Flemish Proverbs from 2014, where the artist is working from Bruegel, or the more recent Berlin Flowers series, carried out on the first Sunday of each month during the first year of the Covid pandemic, developed from this initial engagement with Blake. The fortuitous combination of Blake and a mahogany wardrobe had provided, as it were, a personalized tradition with which to work, and an approach that has proved richly productive for the artist. Blake described his emblems in The Gates of Paradise as ‘The lost Travellers Dream under the Hill’, but Chambers has resisted the characterisation of his work as ‘dream-like’ or ‘surrealist’. What may appear enigmatic or magical to one person, is straightforward and concise narration to another. For example, Claude Lévi-Strauss pointed out to André Breton that the third image included in his survey concerning ‘l’art magique’- a Haida pictograph from British Columbia taken from an 1888 Smithsonian Report – which ‘perhaps seems “magical” to some’, appears to the ethnographer to be simply ‘a very mechanical illustration of a local legend: that of a man swallowed by a marine monster’. Although, as Chambers remarks: ‘I suspect Blake thought that, say, illustrating a baby as a caterpillar was obvious’.

What do the modern artist and the magus of antiquity have in common?

Artists fall into two categories: those that look at history, and those that don’t. I can’t speak for the latter (though there are many good ones), but for me antiquity was my education. Providing me with a yardstick, references, context and precedent. I wonder often, when in the past artists were commissioned, usually by the church, how much of a relief it must have been to have your subject matter prescribed. That’s not how it works today.

Magic seeks to reconcile the forces of nature with human desire. Does art do the same? Does art contribute to the enchantment of the universe?

Art and nature the two great educators. Both evolve, and both (at least when art is working well) make complexity simple. That’s definitely enchanting.

[The first two questions have been adapted from André Breton’s survey of artists and intellectuals carried out for his book L’Art magique (1957).]

You have described the relationship of your paintings to Blake as ‘distanced veneration’. How did this series of paintings come about and what was it about the Gates of Paradise that you found particularly appealing?

I am interested in people that belong nowhere. The mavericks, the misfits, the outliers. Those people that couldn’t join a gang, even if they wished to. This is Blake; The singular outsider wrestling with his place in the world. The Gates of Paradise feel as though they are trying to make logical, the illogical. Though I suspect Blake thought that, say, illustrating a baby as a caterpillar was obvious.

How did these works come to be painted on mahogany panels? Was there an element of ‘objective chance’ at play?

Outside my studio in Hackney was discarded an old mahogany wardrobe. I kicked out the panels which became the series of Blake paintings. For me the term ‘picture’ is pejorative. It suggests a distanced comfort. I make paintings. They are things, units, certain, and a Provocation. The breaking of the normal flatness provided by the panel’s moulding reaffirmed that these were definitely ‘things’.