John Hamilton Mortimer, Caliban from Twelve Characters from Shakespeare, 1775, etching.

Inscription: CALIBAN. Do not torment me prithee / I’ll bring my wood home faster. Tempest Act II. Scene the 2. / Published May 20 1775 by J. Mortimer. Norfolk Street STRAND.

A character in William Shakespeare’s play The Tempest (1611), the monstrous Caliban was the original inhabitant of the island ruled by the former Duke of Milan and magician, Prospero. He was the child of the witch Sycorax (according to Prospero, he was ‘got by the devil himself upon thy wicked dam’). Initially, he was supported by Prospero who taught him language – the main advantage of which to Caliban was that ‘I know how to curse’ – but he was later enslaved after Caliban attempted to rape Prospero’s daughter Miranda. Of Prospero’s two familiars he could be seen as representing base matter as opposed to the spiritual Ariel. Although himself the child of a sorceress who recalls figures like Medea and Circe, Caliban’s complaint against Prospero is that ‘by sorcery he got this isle’ and he leads an unsuccessful rebellion against his master. Prospero’s magic is learnt from books, and his organization of a masque acted by spirits – a play within the play – suggests an analogy between Shakespeare’s poetry and Prospero’s magic. As The Tempest is thought to be Shakespeare’s last play, it has even been argued that the author announced his own retirement when Prospero states in his final soliloquy that ‘now my charms are all o’erthrown’.

The artist John Hamilton Mortimer exhibited twelve drawings of characters from Shakespeare’s plays at the Society of Artists exhibition in 1775. A letter of 27 March 1775 from David Garrick to Mrs Elizabeth Montagu, shows that Mortimer was supported by the famous Shakespearian actor in publishing the drawings as etchings. Garrick asked if he could put Mrs Montagu’s name at the top of a ‘noble list’ of subscribers to the set of prints, and also asked her to canvass support for ‘a most ingenious man’.[1] The etched ‘portraits’ were published in two sets of six in 1775 and 1776. Mortimer intended the characters to be seen as pairs with, for example, King Lear paired with Caliban from The Tempest. Edgar, a character also from the play King Lear, is shown in the persona of ‘Poor Tom’, a mad beggar, demonstrating how Mortimer chose to emphasize the more picturesque and wild aspect of Shakespeare’s plays. The Poet is not so much a representation of a character, but rather of a passage in Midsummer Night’s Dream describing the ‘fine frenzy’ required for poetic inspiration: a reading going somewhat against the grain of Theseus’s speech which prefers ‘cool reason’ to ‘strong imagination’ (Mortimer’s inscription on the print carefully excludes the comparison of the poet to the lunatic and lover).

Theseus: More strange than true: I never may believe

These antique fables, nor these fairy toys.

Lovers and madmen have such seething brains,

Such shaping fantasies that apprehend

More than cool reason ever comprehends.

The lunatic, the lover and the poet

Are of imagination all compact:

One sees more devils than vast hell can hold,

That is, the madman: the lover, all as frantic,

Sees Helen’s beauty in a brow of Egypt:

The poet’s eye, in fine frenzy rolling,

Doth glance from heaven to earth, from earth to heaven;

And as imagination bodies forth

The forms of things unknown, the poet’s pen

Turns them to shapes and gives to airy nothing

A local habitation and a name.

Such tricks have strong imagination,

That if it would but apprehend some joy,

It comprehends some bringer of that joy;

Or in the night, imagining some fear,

How easy is a bush supposed a bear![2]

Mortimer was one of an older generation of artists, born in the 1740s, including James Barry and Henry Fuseli, who were admired by William Blake for their advocacy of inspired genius as the model for artistic creation as opposed to the eclectic imitation supported by Joshua Reynolds in art theory, or the concern to please fashionable high society through glamorous portraiture of an artist like Thomas Gainsborough. Blake’s annotations to his copy of Reynolds’s Discourseskeep up a running commentary on these themes beginning with the statement that: ‘While Sir Joshua was rolling in Riches Barry was Poor & Independent Unemployed except by his own Energy Mortimer was despised & Mocked called a Madman’.[3] Blake also identified Reynolds’s comment that ‘he who would have you believe that he is waiting for the inspiration of Genius, is in reality at a loss how to begin; and is at last delivered of his monsters, with difficulty and pain’ as being a ‘Stroke at Mortimer’.[4] Mortimer included several monsters in a series of fifteen etchings dedicated, in a spirit of friendly disagreement, to Joshua Reynolds in 1778 which continued the development of the proto-Romantic view of artistic inspiration presented in the Shakespearean characters.

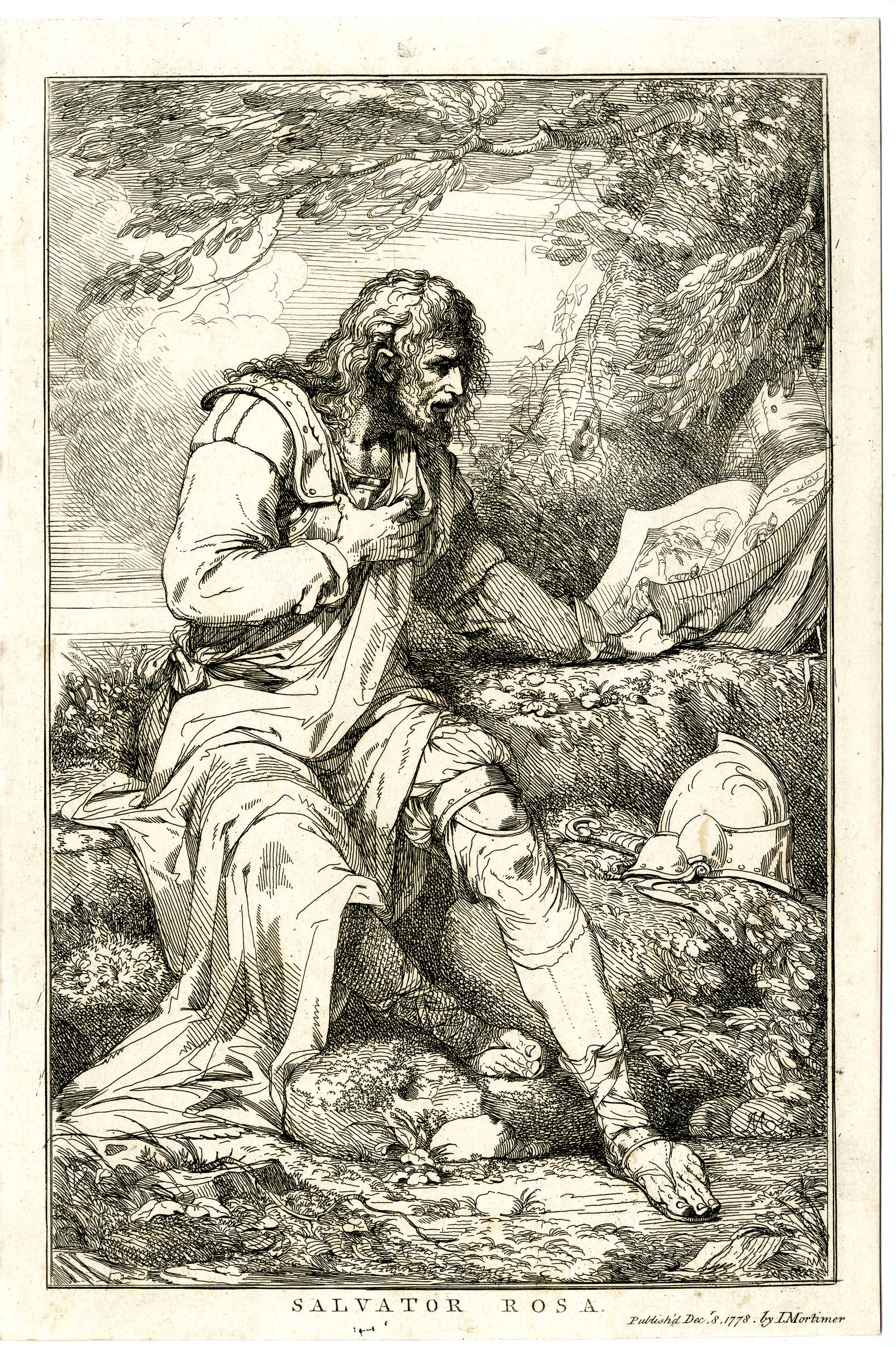

Among the various monsters and banditti in this set of prints were two opposing images of the artist: Salvator Rosa and Gerard de Lairesse. While Rosa represents a heroic conception of the artist, based on one of the virile, armored bandittifamiliar from that artist’s etchings, De Lairesse, the Dutch art theorist, is shown by Mortimer as an infirm and visually-impaired old man hobbling away from the props of his art. Mortimer’s characterization of Salvator Rosa is perhaps closest to Rosa’s own 1664 etching of Jason and the Dragon, where the hero defeats the monster guarding the golden fleece using a magical potion prepared by Medea (itself an allegory of artistic creation?). Blake agreed with Mortimer in opposing the conception of art advanced in Reynolds’s Discourses which he interpreted as Locke, Bacon and Burke transposed to art theory: ‘I read Burkes Treatise when very Young at the same time I read Locke on Human Understanding & Bacons Advancement of Learning on Every one of these Books I wrote my Opinions & on looking them over find that my Notes on Reynolds in this Book are exactly Similar. I felt the Same Contempt & Abhorrence then; that I do now. They mock Inspiration & Vision. Inspiration & Vision was then & now is & I hope will always Remain my Element my Eternal Dwelling place. how can I then hear it Contemnd without returning Scorn for Scorn’.[5]

Incidentally, the painter James Barry gave a useful and succinct summary of the art theoretical case for painting and poetry being sister arts in one of his lectures to the Royal Academy:

All writers of character who have employed their thoughts upon the productions of genius, are universally agreed, that the essence and ground-work of poetry and painting is in every respect the same; and Aristotle’s Poetics and Horaces’ Epistle to the Pisos, will be found just as essentially applicable to painting as to poetry. There is necessary in both, the same glowing enthusiastic fancy to go in search of materials, and the same cool judgment is necessary in combining them. They collect from the same objects, and the same result or abstract picture must be formed in the mind of each, as they are equally to be addressed to the same passions in the hearer or spectator. The scope and design of both is to raise ideas in the mind, of such great virtues and great actions, as are best calculated to move, to delight, and to instruct. In short, according to Simonides’s excellent proverb, “painting is silent poetry, and poetry is a speaking picture”. These arts, or rather, these branches and emanations of the same art, which is design, have, from the nature of the materials they work with, each of them its peculiar advantages and disadvantages. Nothing can give to poetry that precision of form and that assemblage and instantaneous result that painting has. On the other hand, poetry if it loses by the succession of its images in one instance, it gains by it in another; and it has besides, the power of dealing out infinite mental combinations, which no form can circumscribe.[6]

[1] David M. Little and George M. Kahrl (eds), The Letters of David Garrick, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1963, no. 900, 27th March 1775. Cited in Benedict Nicolson, John Hamilton Mortimer ARA 1740-1779, exhibition catalogue, Towner Art Gallery, Eastbourne and Iveagh Bequest, Kenwood, 1968, pp. 41-42.

[2] William Shakespeare, A Midsummer’s Night Dream, Act V, scene 1.

[3] David V. Erdman (ed.), The Complete Poetry & Prose of William Blake, New York: Anchor Books, 1988, p. 636.

[4] Ibid, p. 646.

[5] Ibid, pp. 660-61.

[6] Edward Fryer, The Works of James Barry, II, London, 1809, p. 233.