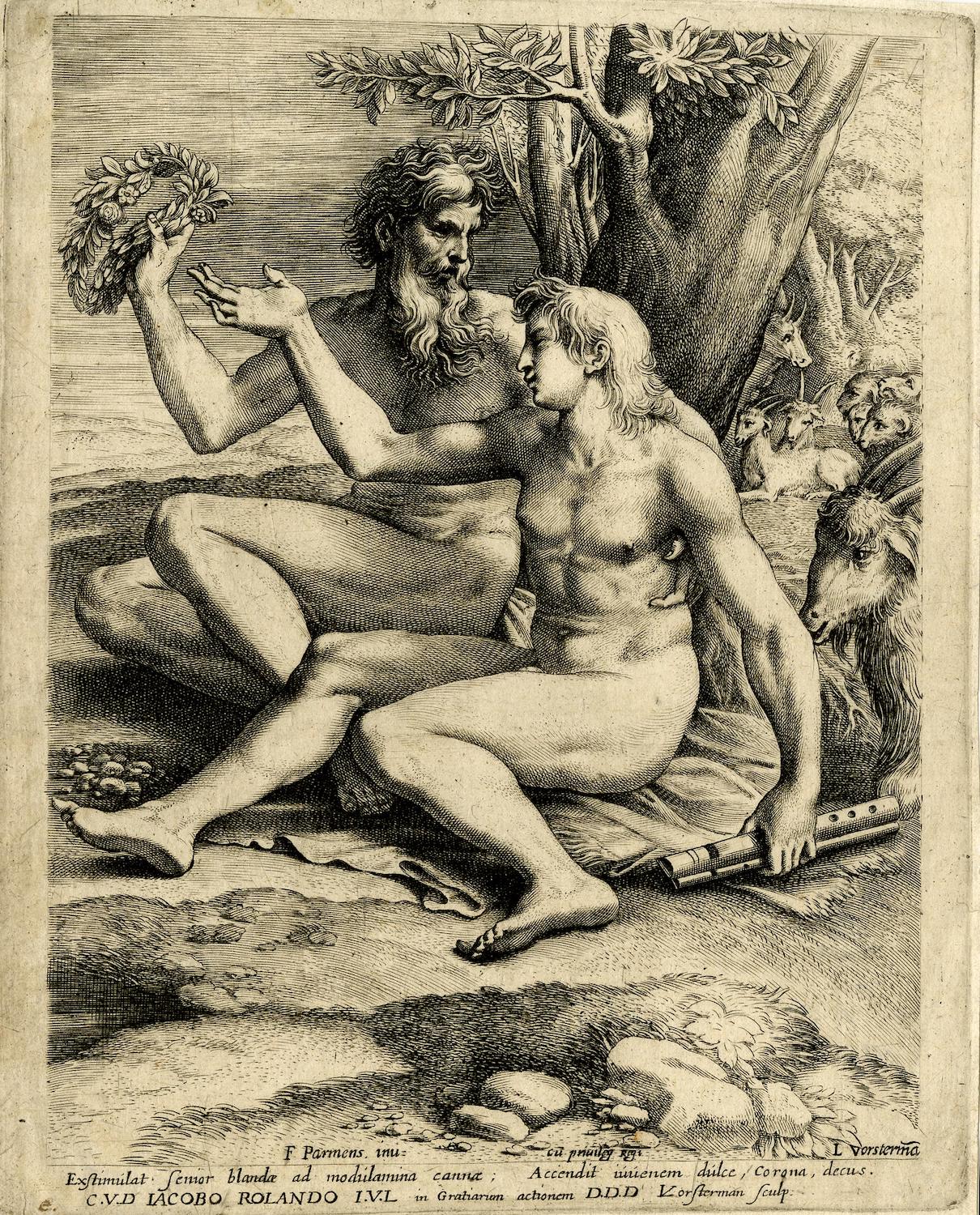

Lucas Vorsterman, Pastoral Scene, after Parmigianino, 1620s, engraving.

This engraving of a pastoral scene reproduces in reverse a carefully finished pen and ink drawing by the Emilian artist Francesco Parmigianino from c.1530-39 now in the Kunsthalle in Hamburg (no. 21267). The drawing has a provenance to the collection of Thomas Howard, Earl of Arundel, and it was presumably while he was working for that great patron of the arts in London from 1623-28 that the Flemish printmaker Lucas Vorsterman engraved it, along with other works in the Arundel Collection.[1] The print carries an inscription dedicating it to Jacob Roland, and a Latin verse, whose source has not been identified, which suggests that the older of the two men in the image is inspiring the younger by his blandishments to earn the garland of honour through the melody of his reed pipes (‘Exstimulat senior blandae ad modulamina cannae; Accendit iuvenem dulce, Corona, decus’). In this context, Parmigianino’s stylish design served as an index of the Italianate and antique tastes of a leading figure in Caroline court culture.

The meaning of the original drawing, however, seems to be obviously homoerotic. As David Franklin has put it: ‘The main lines of the narrative seem clear, even in the absence of a precise identification of the subject. The mortal youth who holds a flute in his right hand receives from the bearded god an offer of immortality in the form of a laurel wreath, which he reaches to take in return for sexual favours’.[2] Whether the two nude men, one bearded and mature, the other a youth, are a god and a mortal, or simply two goatherds, their encounter is subtly sexual with the prized wreath – held out of reach by the older man – being connected through complementary gestures with the phallic pipes held caressingly by the youth. The mood of the scene resembles the yearning eroticism of the pastoral poetry of Virgil’s Eclogues – for example, Corydon’s love for Alexis in the second Eclogue – or of the Idylls of Theocritus.

Poetic recitations often take on an agonistic form in Theocritus’s bucolic verses. In the first Idyll a highly decorated cup is described, itself a prize offered in return for the performance of a song about the sorrows of Daphnis. Represented on it is the scene of two poets competing unsuccessfully for the attention of a Muse: a goddess whose favour is invoked through verse.

‘… Inside the plant’s frame is carved

(Truly God’s craft) a woman resplendent in a dress and circlet.

She stands between two men with fine long hair, who compete

In alternating song, but do not touch her heart. She smiles,

Glances at one, then turns to look at the other, while they,

Their eyes long swollen with love, keep on their useless toil’.[3]

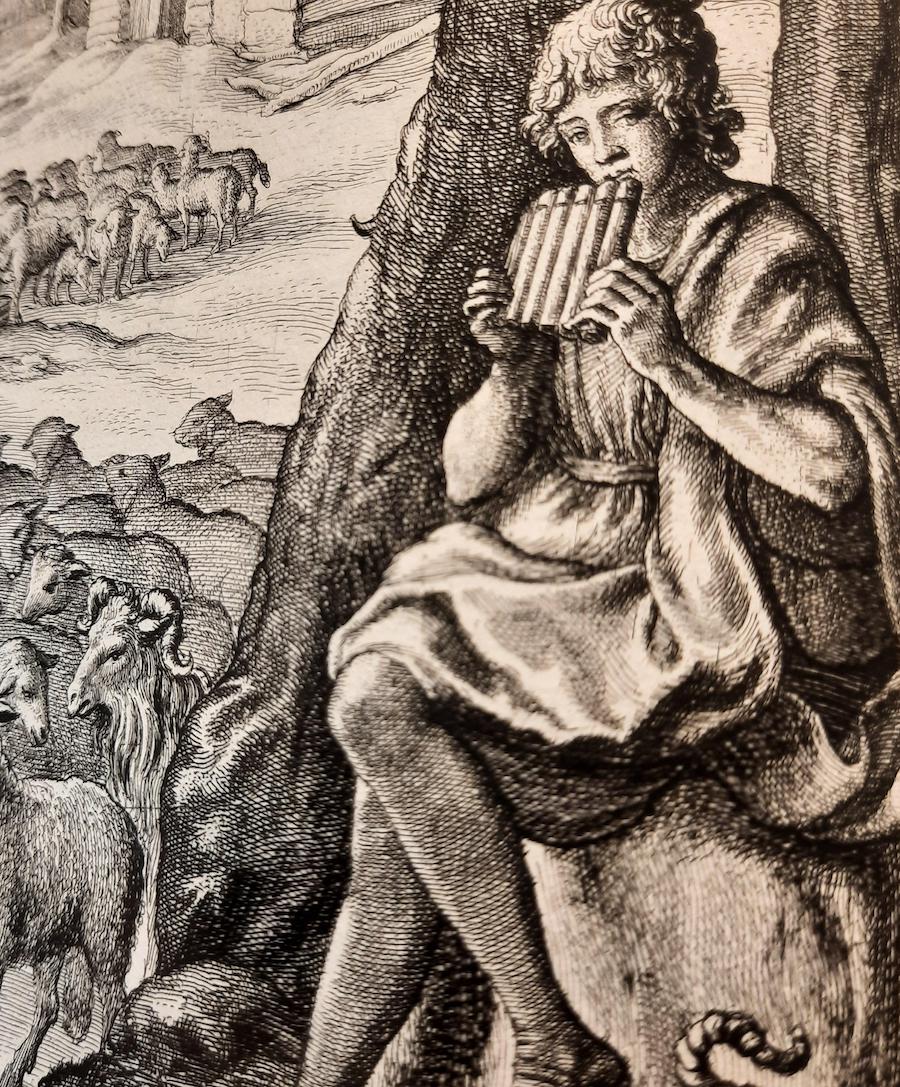

Although reified here, as the description of an ornament on a work of art, poetic competition is alluded to as an ancient ritual, a form of magical bargain with nature. Poetry, therefore, is conceived of as a powerful means of communication with the supernatural forces that pervade nature. The sacred quality of music and song is even hinted at in the prohibition on pipe-playing at midday because this is when ‘Pan rests, you know, tired from the hunt. We’re afraid of him; he’s tetchy at this hour, and his lip is always curled in sour displeasure’.[4]

Seppilli discerned in the somewhat illogical narrative of Homer’s Iliad the traces of ancient heroic cults: those, principally, of Achilles and Helen. These different yet complementary cults involved the ritual re-enactment of a founding myth as a form of initiation. In the case of Helen this involved the ritual competition between groups of young men over a female idol that is abducted – in the process crossing water – and then liberated and restored, connected with a sacred grove of plane trees near Sparta. Both myths ultimately concern themselves with the ‘fundamental problem of the death and rebirth of man and of the cosmos’ [‘la problema principe di morte e rinascita dell’uomo e del cosmo’].[5] The cult of Elena dendritis was seen by Seppilli as preceding and informing Homer, and she points out that Theocritus also referred to it in the eighteenth Idyll:

‘We shall be the first to plait for you a wreath of ground-loving

Clover to hang on a shady plane tree, and we shall be the first

To make an offering of gleaming oil, dripped from our silver flasks,

Under that plane tree’s shade. In its bark we shall cut these words, that

Passers-by may read its Dorian message: “Respect me; I am Helen’s tree”’.[6]

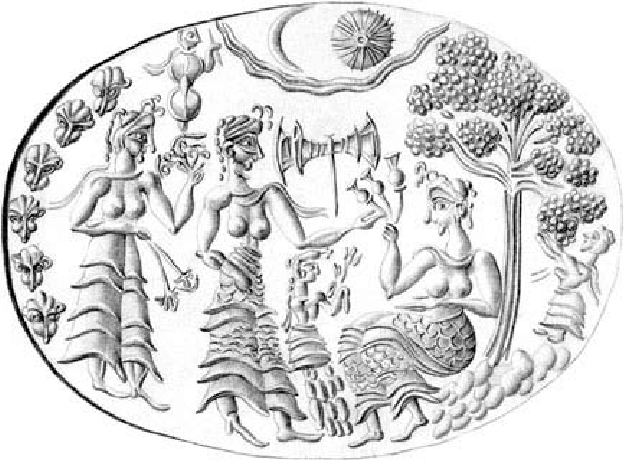

Before she was a mortal princess, therefore, Helen was a goddess of vegetation associated with a tree cult and, according to Seppilli, possibly with the institution of hierogamy or sacred marriage (a more recent and extensive analysis of ‘Helen’s Divine Origins’ has been provided by Lowell Edmunds). Helen of the Trees also had a sanctuary at Rhodes because, according to Pausanias (iii, 19, 10), Queen Polyxo had her hanged from a tree to avenge her husband Tlepolemus. Robert Graves related these legends to the existence of dolls that were hung from fruit trees to ensure that the crops grew, as depicted on a gold ring found in the Acropolis Treasure at Mycenae (now in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens). The image on this ring has prompted various interpretations, including that it demonstrates that existence of a tree cult linked to a Minoan fertility goddess, and possibly the ritual use of opium.[7] For Seppilli, Helen of Troy was ultimately the ancient fertility goddess Potnia (‘Lady’), the mistress of the Labyrinth who preceded the Olympians, whose identity was later conflated with Kore (Persephone), the mistress of the Eleusinian mysteries: ‘Helen is therefore linked to the plant whose seed dies and is reborn, perhaps to the moon which descends to the underworld and is reborn; she is linked to the marriage rite, which always has, even among the Greeks, a very close analogy with death, it is indeed a rite of death and descent into the underworld and of rebirth, and therefore it follows the story of the seed; in fact, if it does not descend to die in the womb of the damp earth, the seed cannot rise again to life, it is not fertile and does not bear fruit. In this sense, Helen certainly corresponds to the great pre-hellenic Potnia…’ [Elena è dunque legata alla pianta il cui seme muore e rinasce, forse alla luna che scende agli inferi e rinasce; è legata al rito matrimoniale, che ha sempre, anche fra i Greci, strettissima analogia con la morte, è anzi un rito di morte e discesa agli inferi e rinascita, e perciò ricalca la vicenda del seme; se infatti esso non scende a morire nel grembo della terra umida, non può risorgere alla vita, non è feconda e non dà frutto. In questo senso Elena certo corrisponde alla grande Potnia preellenica…][8]

Daphnis, like Helen, is also linked with vegetation and the natural cycle of the year. His name derives from the laurel growing in the grove where he was exposed as an infant. The son of a god, Hermes, he remained mortal. The love and jealousy of nymphs caused him suffering, blindness and even to be transformed into a stone (Ovid, Metamorphoses, IV, 274). He was taught how to play the pipes by Pan, the god whose pursuit of the nymph Syrinx resulted in her transformation into marsh reeds through which the wind blew to create music: desire transformed into art through a form of enchantment literally ‘inspired’ by nature. Several antique sculptural groups of Pan and Daphnis exist (including this one in the Uffizi), representing the rustic god teaching his young lover how to play the syrinx pipes. Parmigianino probably had the example of such antique statues in mind when he drew his rustic pair of goatherds. Like Persephone, and like the poet Theocritus, Daphnis, the inventor of pastoral poetry, is also closely associated with Sicily. The magic spell ‘make Daphnis come home now’ aims at the rebirth of the Sicilian Spring.

[1] On Vorsterman in England see: Antony Griffiths, The Print in Stuart Britain 1603-89, London: British Museum, 1998, pp. 71-80.

[2] David Franklin, The Art of Parmigianino, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2003, no. 84, pp. 264-67.

[3] Theocritus, Idylls, translated by Anthony Verity, Oxford: World Classics, 2008, p. 3.

[4] Ibid, p. 1.

[5] Anita Seppilli, Poesia e magia, Torino: Einaudi, 1971, p. 457.

[6] Theocritus, p. 60. This Idyll is a third-century recreation of an archaic Spartan wedding song from the Sixth Century BC. Its revival could be related to Ptolomaic policy on marriage in Egypt where Helen had cult status.

[7] Robert Graves, Greek Myths, London: Cassell, 1955, p. 298, note 10.

[8] Anita Seppilli, Poesia e magia, Torino: Einaudi, 1971, p. 419.