This is a copy of a piece I wrote for the Physics & Astronomy Student Newsletter at the University of Kent.

If you’re mildly terrified by the thought of a robot deciding to open you up and perform delicate surgery, as all sensible people surely are, then you don’t need to succumb to sleepless nights just yet. While robotic surgery is most definitely with us – there over 3 million procedures per year globally – the robots aren’t in charge. For now at least, the surgeon is still sat nearby at a console, directly controlling the robot, and taking advantage of the extra dexterity that comes from using robotic tools rather than human hands.

The US company Intuitive Surgical currently dominates robotic surgery with their da Vinci platform, and almost all procedures carried out currently use their hardware. But venture capital has been flowing into this arena, and there are dozens of start-ups now chasing what could be an enormous global market, including CMR Surgical in the UK.

All good robots need eyes, and if we are endowing the surgeon with super-human dexterity then we might as well offer them better than 20/20 vision as well. Newsletter readers will know that we have a long history of optical imaging research here at Kent, and applying this to medical robotics is becoming an increasingly important focus for some of us in the Applied Optics Group.

My own interest in this area began back in 2011. After a brief foray into hospital physics following my PhD, I had decided to apply to a (perhaps intentionally) vague job advertisement for an optical physicist for a research associate post (a ‘postdoc’ as they are known) at Imperial College. As it happened, I had exactly the background needed, and I ended up spending 6 years working at Imperial’s Hamlyn Centre for Robotic Surgery. This had been set up a few years earlier by Prof Guang-Zhong Yang and Lord Ara Darza, a pioneer of keyhole surgery and former minister in the Department of Health. With an endowment from the Hamlyn Trust, the Centre was aiming to make new developments in medical robotics, and where possible commercialise them.

The Centre was a mix of roboticists, computer vision specialists, surgeons and the odd optical physicist such as myself. We were split over two sites, a main engineering centre on the Imperial College site in South Kensington, and another facility at St Mary’s Hospital, the other side of Hyde Park. Lots of research grants, combined with the endowment, had led to a very well-funded centre and some pretty exciting toys, including a fantastic suite of industry-grade 3D printers and, of course, some surgical robots. But all this came with high expectations and an intense workload to match; we were expected to get results quickly, alongside running an annual conference and catering to a constant stream of high profile visitors, from House of Lords committees to President Xi Jinping.

I worked almost entirely on endoscopic microscopy – building very small and flexible fibre optic microscopes that could be used to capture high resolution images of tissue during surgery. The idea was that these could be used to guide robotic procedures, to give the operator the kind of view that would normally first require taking a biopsy, then sending it to a histopathology lab and waiting a couple of days for the results. Since we wanted to image tissue in situ, the microscope has to be what is known as ‘confocal’, meaning that it only collects light from a thin layer of in-focus tissue. Otherwise the useful image would be drowned out by blurred light from all the out-of-focus layers. We worked for a while on building a system that could capture these confocal images very quickly [1]. This meant that we could scan the tip of the microscope rapidly over the tissue using the robot, compensating for the relatively small imaging area that the small probes were able to achieve [2], and even use the microscope images for precise control of the robot’s motion.

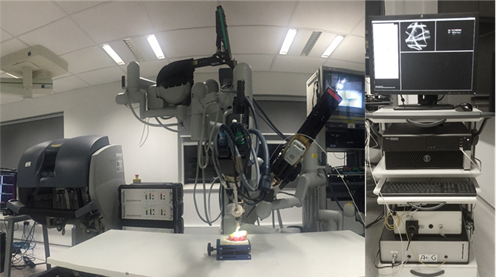

Towards the end of my time at Hamlyn, we began a collaboration with the Applied Optics Group here at Kent, particularly with Prof Adrian Podoleanu and Dr Adrian Bradu, who was then a postdoc. The Kent team built and installed an Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) endoscopic probe in the labs at St Mary’s Hospital, which we began using together with the da Vinci for pre-clinical research [3]. We then received a large grant from the Engineering and Physical Science Research Council, called ‘REBOT’ to work together on image guided robotic probes for lung imaging. In 2017, myself and Adrian Bradu were appointed as lecturers at Kent and so I moved across here, with Dr Manuel Marques taking over Adrian Bradu’s postdoc role on the project. My change of jobs meant that the grant no longer paid for any of my time, but the University was able to give reduced teaching loads new lecturers, and I was able to stay involved with the project. We published some nice papers with promising results showing how OCT endoscopes could be scanned over tissue using either a robot or a manual endoscope [4,5], although some staff changes at the Hamlyn Centre made it difficult to build on the work after the funding ended.

In 2021, myself and Adrian Podoleanu began a new collaboration with Dr Christos Bergeles at King’s College London. We joined a funding bid led by King’s and were awarded £1.5M between us from the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) to develop a robotic system for retinal surgery. Kent’s contribution is to develop an optical distance sensor and imaging system that can be incorporated in to millimetre sized tip of the robot (essentially a steerable need that goes inside the vitreous of the eye). This is a challenging bit of engineering, to say the least, and has drawn on expertise in the AOG that is unique in the UK. Manuel Marques was initially the postdoc on the project, but he too was promoted to lecturer in 2022 (optics & robotics is virtually a guarantee of career success it seems) and so Dr Radu Stancu joined us shortly after, with Manuel remaining an integral part of the team. We have already reported the distance sensor at several conferences; and while the imaging system is still under wraps for the time being, we should have some exciting results to share soon.

This is unlikely to be our last foray into robotics, and we sometimes offer MPhys/MSc/PhD projects in this area. If you’re interested in finding out more, please get in touch.

[1] https://doi.org/10.1364/BOE.7.002257; [2] https://doi.org/10.1109/TBME.2018.2837058; [3] https://doi.org/10.1109/MRA.2017.2680543; [4] https://doi.org/10.1364/BOE.444170; [5] https://doi.org/10.1117/1.JBO.24.6.066006