Ph.D researchers from the Centre for Medieval and Early Modern Studies and the School of History at the University of Kent, Amilia Gillies and Eleanor Hex, reflect upon the study day on Monday 11th March 2024, which celebrated the Cathedral’s acquisition of the marvellous painting, Thomas Johnson’s ‘Quire of Canterbury Cathedral’ of 1657.

One cannot deny the numinous beauty of Canterbury Cathedral. Standing in the quire, the sight of the Corona Chapel at the east end is entirely other-worldly. Beneath the soaring vaulted ceilings, among the impenetrable columns, the light purpled slightly, owing to the intricate stained-glass, one cannot begin to fathom how many before us have marvelled at this sight. Today, we can enjoy a view seen by countless individuals, including the architect, William de Sens, who commenced the major re-building project after the disastrous fire of 1174, the medieval pilgrims from across Europe who made treacherous journeys to the Cathedral to venerate the shrine of St Thomas Becket, numerous royal visitors and diplomats over the centuries, and the anxious citizens who, in fear of its total obliteration, protected the Cathedral with sandbags during the Second World War.

Although the Cathedral still stands firm, parts which were once at its core – notably the shrine of Becket which was destroyed in 1538 during the first English Protestant Reformation under Henry VIII – are no longer there. Destruction is an important part of the Cathedral’s history. While the concept of ‘destruction’ is usually incongruous with the creation of art, Johnson’s ‘Quire of Canterbury Cathedral’ of 1657 gives us a rare visual representation of a later phase of iconoclastic destruction in action. We are transported back to December 1643, when windows were smashed, tapestries were seized, and statues, images and other significant religious items were destroyed, as Johnson illustrates through the tiny piqued, pike-armed figures in his painting.

This remarkable work of art, which is also the earliest known depiction of the Quire, has recently entered the Cathedral’s collection from the Caroe family, who had owned it since 1910. On Monday 11th March 2024, the Cathedral Archives and Library, in conjunction with the University of Kent’s Centre for Medieval and Early Modern Studies, and with support from the University’s Centre for Heritage, held a study day to mark the arrival of the painting to the Cathedral. The event was a huge success. We heard seven fascinating papers from experts in the fields of medieval and early modern history and the history of art. Each approached the work from a different angle, meaning those in attendance came away from the day enthralled and enriched by the depth and range of history that emanate from this piece. The wonder of it being that so many stories are held within its frame – some glaringly obvious and others that one must look deeper to find.

With the Cathedral standing prominently in our view from the window of the Kentish Barn at the Cathedral Lodge, we were given a warm welcome by the Canon Librarian, the Reverend Dr Tim Naish, the Archives and Library Manager, Cressida Williams, and Senior Lecturer in Latin and Palaeography at the University of Kent, Dr David Rundle.

David started off the first session of the day: ‘Canterbury and 17th-Century Iconoclasm’ – a fitting start, providing us with an understanding of the political and religious climate in which Johnson worked. Our first speaker, Professor Ken Fincham, Emeritus Professor at the University of Kent, delivered a paper entitled, ‘Iconoclasm in the 1640s and 1650s: Context and Content’. Ken provided a rich overview of the burst of iconoclasm which occurred around the time that Johnson painted; a burst which can be situated during England’s second Reformation. While the first Reformation saw Protestants turning on Catholics, the second saw Protestants turning on other Protestants. Predominantly in the leadup to the toppling of the monarchy and episcopal order, puritanical Protestants believed that the Church of England had not been reformed enough, paving the way for a spike in iconoclasm. Felicitous to the day’s architectural theme, Ken showed images, including a photograph of one of the victims of the destruction, which has since been reassembled: the Cathedral’s remarkable font, erected in 1639 under Archbishop William Laud, complete with figures of the four Gospel writers, Christ and the Holy Dove – all which sat uncomfortably with Puritan opinion. Leading us through other examples, such as the East Window at King’s College, Cambridge, which depicts Christ on the cross, his paper raised the question over why some items and images survived the iconoclastic spate, while others did not. Canterbury and other cities may be vastly different today had the iconoclasts not stopped when they did!

Secondly, we heard a paper written by Professor Jackie Eales, Emeritus Professor at Canterbury Christ Church University. This bore the striking title, ‘The Most Hated Man in Kent: Richard Culmer and Civil War Iconoclasm in Canterbury Cathedral’. Unfortunately, Jackie could not be present due to illness; however, Ken kindly delivered her paper. We learnt about Culmer – who is most likely one of the figures in Johnson’s painting – the Kentish clergyman, famous, or infamous, for having led the iconoclastic destruction in the Cathedral in 1643. Jackie’s inclusion of evocative quotations from Culmer’s own account, published in 1644 in his Cathedrall newes from Canterbury, notably Culmer’s triumphant description of himself ‘on the top of the citie ladder, neer 60 steps high, with a whole pike in his hand ratling down proud Becket’s glassy bones’, enabled us to picture what truly went on in that fateful December of 1643. Her paper thus raised the intriguing question of why Johnson decided to airbrush away the calamity by depicting a rather calm scene in his painting. Jackie also raised Culmer’s interestingly controversial legacy. Despite having stirred outrage in some, to others, such as the vicar of Monkton, Nicholas Thoroughgood, he was remembered as a ‘loving, faithful friend’.

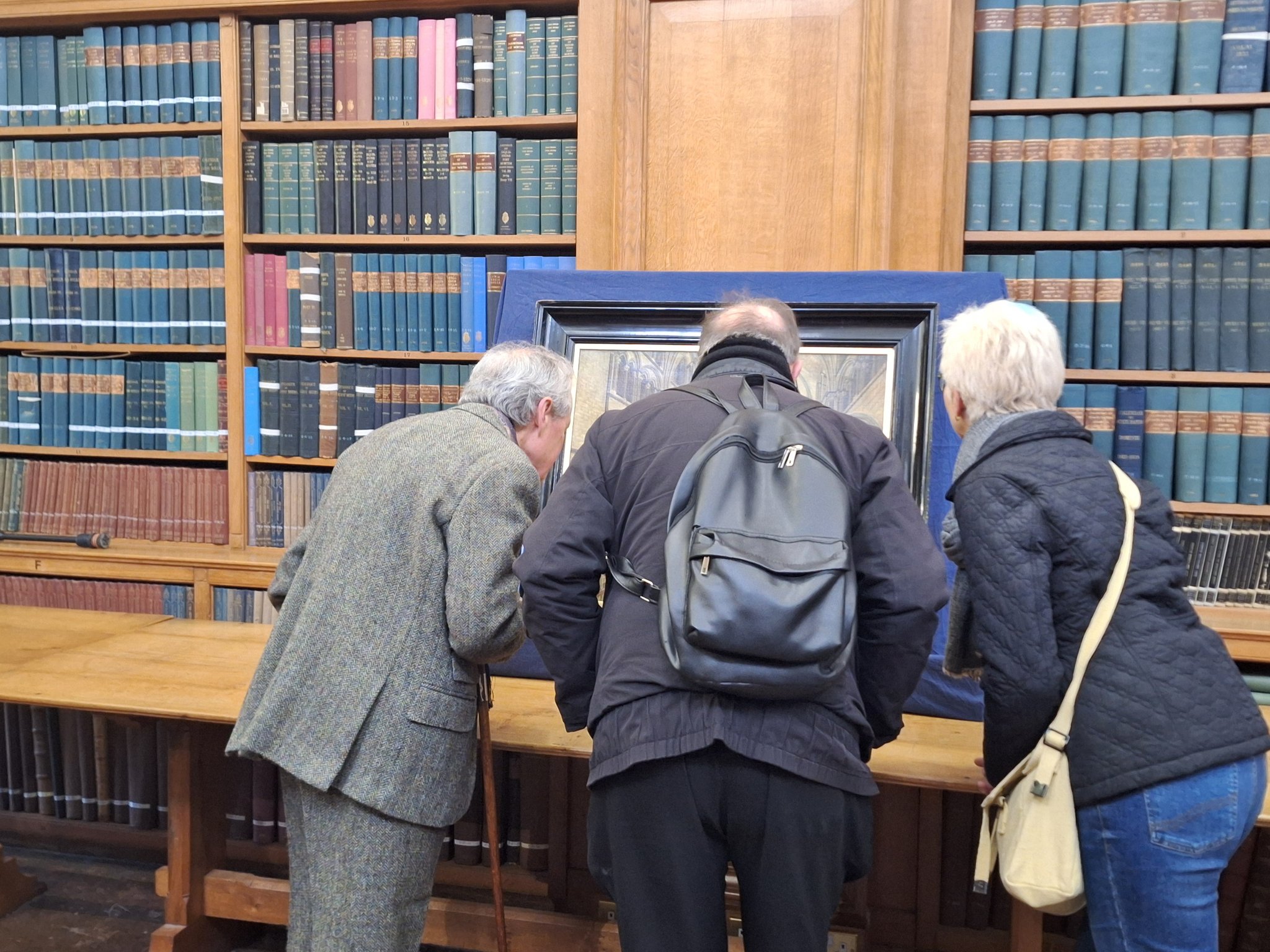

Then, we had the opportunity to see the wonderful painting ourselves in the Cathedral Archives. Sitting on a desk at the far end of the main archive room, the painting had an unassuming air about it. People took their time getting close up to the frame and examining the painting in detail. Attendees could be heard exclaiming in surprise about the size of the painting, expecting it to be so much larger. How Johnson was able to create details so minute speaks to his mastery as a painter and also raised questions about his style and practice as an artist which were answered in discussions by Léonie Seliger and Rachel Koopmans later in the afternoon.

Canon Tim welcomed us to the next session, ‘Damage and Survival’. First up was Léonie Seliger, the Director of Stained Glass Conservation at the Cathedral, who delighted us with a paper entitled, ‘Recording Damage: The Stained Glass in Thomas Johnson’s Painting as a Measure of Accuracy’. The audience was mesmerised by Léonie’s high quality close-ups of the painting’s details, drawing attention to the little figures which one may miss upon first glance. These figures, particularly the one smashing a window bears much resemblance to Culmer’s own descriptions of window-smashing. Our jaws dropped even further when Léonie compared the painting with a modern photograph, taken from the exact spot that Johnson stood while painting. This demonstrated that little has changed overall and convinced us that Johnson was highly accurate in his representation of the architecture. His inclusion of the most minute details, suggest that he likely used a telescope!

Then we heard a wonderful paper from Dr Emily Guerry, Senior Lecturer in Medieval History at the University of Kent, entitled ‘Surrounded by Saints: New Evidence for the Lost Gothic Paintings in the Vaults of Canterbury Cathedral’. Emily pointed out a fascinating detail in Johnson’s painting – the walls of the Corona Chapel, where Becket’s head reliquary was once housed, were painted blood red. Despite the paint having since been stripped, Emily pointed out that flecks of red are still visible, reminding us of the greater prominence that Becket’s cult once had in the Cathedral. Emily took us back even further than the early modern period, focusing on a wonderful set of illustrations of paintings of approximately 74 saints, including Dunstan, Edward the Confessor and Catherine of Alexandria, which were on display around the Trinity Chapel from 1220, probably before Becket’s translation. Interestingly, the images of the female saints were displayed on the north side of the chapel, strongly suggesting that Canterbury followed the tradition of other buildings, such as the Basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna, Italy. Emily’s talk also spoke about the careful work of three artists in preserving the paintings that once graced the cathedral walls. George Austin, clerk of the works at the Cathedral between 1787-1848, painstakingly recorded the fragmentary murals giving these saints a second life. His son, George Austin Jr. copied his father’s works in watercolour. Finally in 1929, E. W. Tristram also copied a version of the murals. There is something strikingly beautiful about this; an act of resistance against destruction. The actions of these artists are anti-iconoclastic, and thus have preserved these images for future generations.

Thirdly, we heard from Dr David Rundle, who captivatingly approached the theme of destruction through the example of the Cathedral’s medieval library, delivering a paper entitled ‘Passion in Pieces: the Cycle of Recycling Manuscripts in Canterbury Cathedral’. We learnt that iconoclasm does not need to be of a moment. A different kind of destruction was going on in the Cathedral’s collection of medieval books. A living library is organic; it naturally grows but also declines in its number of books. David’s research has revealed that the making of books, in the medieval and into the early modern period, often began with the breaking of books, with fragments from older manuscripts being recycled to make new ones. The audience was treated with images of such books, including CCA. MS Add. 128/2, Historia tripartita. A full folio from a pre-Reformation manuscript has been recycled to make the aforesaid example’s wrapper, yet as David pointed out, the old sheet has not been vandalised in any way. These examples strongly suggest that a confessional divide was not driving the process of breaking these pre-Reformation books. The process of surviving is the act of salvaging.

David’s contribution was a fitting end to this session, allowing us to contemplate once again not just destruction but the response to this. After a morning focused on the physical violence of iconoclasm a light was effectively shone on methods of preservation and redevelopment.

Our third and final session, which we were welcomed to by Dr Emily Guerry, was entitled ‘From Becket to Johnson’. This session spanned centuries enabling the audience to consider Canterbury Cathedral’s place in the chronology of destruction from one Thomas to another. The first paper was delivered by Professor Rachel Koopmans, Associate Professor of History at York University, Toronto. ‘The Life and Work of Thomas Johnson’, which she delivered via video link, took us on a rich tour through the life of our artist himself. She described Culmer as a Canterbury man, a convinced congregationalist, and an artist skilled in accurately capturing architectural beauty. The 1657 painting was just one of Johnson’s works on Canterbury Cathedral. Rachel showed us some of his other works, including his drawings for the engravings in William Dugdale’s Monasticon Anglicanum of 1655. Rachel conveyed how during the 1650s, when our painting was produced, the Cathedral would have been very familiar to Johnson, for he was living in rented accommodation in the Precincts! Rachel raised the vital question over why Johnson chose to capture the sacking of the Cathedral fourteen years after it had happened. The appearance of the painting was most likely associated with a resurgence of anti-Culmer sentiment. 1657 also saw the publication of Culmers crown crackt with his own looking-glass, a pamphlet which mocked him viciously. Rachel raised a similar question to Jackie Eales: why did Johnson convey the destruction of the Cathedral so serenely? Could Johnson be purposefully challenging the anti-Culmer sentiment?

Our final paper of the day was delivered by Dr John Jenkins, Co-Director for the Centre of Pilgrimage Studies at the University of York. Entitled ‘The Shrine of St Thomas: Disaster from Beginning to End’, the talk focused on the shrine of Becket, which stood at the east end of the Quire. Although the shrine was long gone by the time Johnson stood to capture what he saw in 1657, John’s paper gave us a broader understanding of destruction in the Cathedral. John excited us with the theory that the fire of 1174, which sparked the major rebuilding project led by William de Sens, was started deliberately; however, as he also explained, it is highly possible that the fire was started accidentally. We were then wowed with a reconstructed image of Becket’s shrine, created by him and his team at the Department of History and the Centre for the Study of Christianity at the University of York. Under Thomas Cromwell’s orders to destroy the shrine in 1538, soldiers took 4,994¾ oz of gold and jewels; 4,425 oz of gold-plated material; 840 oz of partially plated metal; and 5286 oz of silver! This nod to a previous period of iconoclastic activity served to remind the audience of the consistency of change to religious sentiment. Yet through it all since its foundation in 597 Canterbury Cathedral has been a beacon and bastion of the Christian faith, despite what some would do to alter this.

Before the day drew to a close, we heard from Oliver Caroe, whose great-grandfather, the surveyor of Canterbury Cathedral, acquired the painting in 1910. Oliver touchingly recounted his memories of the painting hanging in his grandfather’s dining room, referred to affectionately as ‘Canterbury’, it was part of the landscape of the house. Today, Oliver is delighted for the painting to be entering a new phase in its story; part of the transformation is passing it on. This is all the more poignant, as Oliver explained, for the painting and the themes of destruction and survival speak to the now, in terms of populism and political discourse. He expressed his delight at the conversations that have been sparked, and his hopes that we keep speaking with this fantastic painting!

To some, it may seem strange to have a full day of discussion deriving from ‘just’ one artefact. However, this study day proved the importance of stopping, pausing and considering how much something can tell us. As we learnt from our wonderful speakers, ‘Quire of Canterbury Cathedral’ opens us up to a whole wealth of histories. From national events such as the reformation, to family histories such as that exhibited by Caroe. To have a piece of artwork so openly displaying this act of organised destruction raises questions about the depiction of such events. Whether as an act of propaganda for iconoclasm, or as a warning against similar acts in the future, the painting brings the actions of iconoclasts into focus. Iconoclasm is not just an intellectualised term by which past events of religious division can be categorised; it was a practice of physical violence. This painting reminds its viewer of the desire of one religious faction to completely eradicate the existence of another, a practice which continues into our own times. ‘Quire of Canterbury Cathedral’ provides the viewer with a space to contemplate the impact of destruction; reflecting on what has been lost in the past and what needs to be done to protect artefacts in the future.

For another report on the day, see Sheila Sweetinburgh’s blogpost.