Medieval Hythe & civic uses of sacred space by Sheila Sweetinburgh

Church upper spaces and their uses by Toby Huitson

Masonry sculpture: Hythe’s carved stone fragments by Heather Newton, Canterbury Cathedral

Church tours by Imogen Corrigan and Andy Mills

Document workshops: Jackie Davidson and Sheila Sweetinburgh

Report:

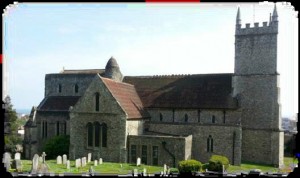

This was a terrific Study Day; excellent speakers and guides; immaculately planned; well-attended (by over eighty people) and not least splendidly catered by kind, generous and caring people. Even the sun shone – St Leonard clearly smiled upon the Churches Committee. Mary Berg gave a warm welcome to the speakers, guides and delegates, principally from KAS and MEMS and we began straightaway.

Dr Sweetinburgh first gave some brief background on medieval Hythe and its magnificent church.

Dr Sweetinburgh first gave some brief background on medieval Hythe and its magnificent church.

Medieval Hythe & civic uses of sacred space by Sheila Sweetinburgh

Context

Hythe was and is one of the Head Ports of the Cinque Ports and should not be studied in isolation since the privileges of this group of towns permitted its members greater self-governance over several centuries and thus the Cinque Ports collective and individual town records provide an insight intoseveral aspects of medieval urban identity. Although the Anglo-Saxon origins of Hythe are unclear, there is evidence that the area was of some importance before the Norman Conquest, specifically for salt production, trading and fishing. Recent excavations by Reading University’s archaeological team at Lyminge have uncovered evidence of a royal court and a monastic community too. A charter of Alfred the Great gave lordship to Christ Church, Canterbury. Hythe was linked to Saltwood, the man or held by the Archbishop of Canterbury, whose tenant held by knight service. The value of this man or doubled during the eleventh century, and some of the nine mills recorded at Domesday may have been at Hythe, and likewise, perhaps, one or two of the churches in Lyminge manor because the town’s 231 burgesses were answer able to either Saltwood or Lyminge. Norman and Angevin Hythe enjoyed a growing population and a thriving economy –a mint first began operating between 1042 and 1100. Saltwood Castle was rebuilt and cross-channel and coastal trading increased as the other Kentish Head Ports of Dover, Sandwich and New Romney grew in importance too. From the 1230s the town sought greater self-governance, with its own officers, own common seal, and its own town courts so it was no longer answerable in the manor courts. The provision of ship service to the crown brought exemption from royal taxation (lay subsidies),nor were the Ports men required to appear in other courts, privileges that aided the mercantile and fishing activities of the towns people who increasingly grouped together in similar activities, with the fishermen in the west part near to St Nicholas chapel (at New Romney, too, St Nicholas’ was their church), Our Lady in the east and St Leonard’s chapel in the centre. These differing areas of activity and their separation are an important aspect of town development, one also noticed not only in Dover and Sandwich, but also in Thanet and North Kent, and in West Country medieval towns. In Hythe, the well-to-do jurats and freemen (or barons as they were called in the Cinque Ports)interacted with the local aristocracy, fellow  Cinque Port officials, the archbishop and the king, a substantial achievement for a small fishing and trading port, its four chapels (St Nicholas’, St Michael’s, St Leonard’s and Our Lady) numerically on a par with Dover.

Cinque Port officials, the archbishop and the king, a substantial achievement for a small fishing and trading port, its four chapels (St Nicholas’, St Michael’s, St Leonard’s and Our Lady) numerically on a par with Dover.

However, matters were to deteriorate substantially in the later fourteenth century, due to plague, a great fire, and the inexorable silting of the haven as a result of long shore drift. In 1412 the jurats petitioned to abandon the town. Yet the town did not die, and during the later fifteenth century the local records, the Maletotes, indicate some families were doing rather well even if the town itself had not recovered. For example, from 1366 only one chapel continued in Hythe, St Leonard’s, like its ‘lost’ fellows a daughter house of Saltwood’s parish church.

Civic Uses of Sacred Space

Yet chapel hardly does justice to St Leonard’s. Connections to Christ Church, Canterbury and the Archbishop of Canterbury meant that St Leonard’s received some serious archiepiscopal and architectural attention in the Norman and Angevin period, probably by the same local masons who worked on the cathedral’s new quire and Trinity Chapel in the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries. They forged a unique sacred place that dominated the town and served as a landmark for shipping. No wonder Hythe’s civic customs were interlocked so securely into the sacred space. It was this interconnection that formed the core of the lecture – drawn from extensive research into the Cinque Port custumals, wills and churchwardens’ accounts, and the church fabric itself, using the documentary evidence to contextualize the varied usages of the medieval building. The key adjective in understanding these medieval usages is ‘performative’ – actions, speeches and knowledge were all needed to form a collective and individual identity for the town – a civic performativity given a sharp prod by the quo warranto activities of Edward I eager to reclaim crown privileges which had lapsed in his father’s reign and, of course, outside lordships such as the Archbishop of Canterbury. Hythe did not have a mayor until the late sixteenth century – but it had a number of ritualised elements – just as the other Cinque Ports such as Sandwich and Dover. Hythe jurats swore oaths and were chosen from the franchise of the town – the freemen, in-dwellers and householders – the venue for the election, the muniment chest and civic paraphernalia, all lent legitimacy to the proceedings, as did the moot horn summoning all those eligible to elect the jurats in the town’s liberty. This then was a blend of ritual and oral, aural and visual traditions held on particular dates – Hythe’s held its elections on the Purification of the Virgin Mary on 2nd February; New Romney on 25th March – the Annunciation; Dover on 8th September – the Nativity, and Sandwich for two days after 30th November St Andrew’s Day – these dates also linked into the fishing seasons. At election jurats were chosen by counting pinpricks in a paper against the electors’ names. The vote was made in front of the outgoing jurats and eligible townspeople who could fit inside St Edmund’s Chapel in the north transept of St Leonard’s. The newly-chosen jurats then swore oaths to uphold the town and its people and kissed the Bible before their audience and witnesses. The ancient and sacred space gave the civic event an added piety. In New Romney a tomb of a former jurat formed the table for the election. Performance in the ancient chapel of Hythe also made the dead witnesses to the devotion and civic pride of the living; and was thus both a celebration of the town and a commemoration of their forefathers. As the oaths may have been sworn in front of an altar, or image (there was one to the Blessed Virgin Mary in St Edmund’s chapel) this election gave the civic authority sanction from God – jurats were in some sense divinely appointed too, adding sacrality to the customs of the town that had been performed ‘time out of mind’. The ceremony was possibly followed by a mass, a procession, and a feast. As Sheila Sweetinburgh summed up; St Leonard’s was a political as well as a sacred space symbolising the importance of the relationship between the town officers and the church in Hythe.

lordships such as the Archbishop of Canterbury. Hythe did not have a mayor until the late sixteenth century – but it had a number of ritualised elements – just as the other Cinque Ports such as Sandwich and Dover. Hythe jurats swore oaths and were chosen from the franchise of the town – the freemen, in-dwellers and householders – the venue for the election, the muniment chest and civic paraphernalia, all lent legitimacy to the proceedings, as did the moot horn summoning all those eligible to elect the jurats in the town’s liberty. This then was a blend of ritual and oral, aural and visual traditions held on particular dates – Hythe’s held its elections on the Purification of the Virgin Mary on 2nd February; New Romney on 25th March – the Annunciation; Dover on 8th September – the Nativity, and Sandwich for two days after 30th November St Andrew’s Day – these dates also linked into the fishing seasons. At election jurats were chosen by counting pinpricks in a paper against the electors’ names. The vote was made in front of the outgoing jurats and eligible townspeople who could fit inside St Edmund’s Chapel in the north transept of St Leonard’s. The newly-chosen jurats then swore oaths to uphold the town and its people and kissed the Bible before their audience and witnesses. The ancient and sacred space gave the civic event an added piety. In New Romney a tomb of a former jurat formed the table for the election. Performance in the ancient chapel of Hythe also made the dead witnesses to the devotion and civic pride of the living; and was thus both a celebration of the town and a commemoration of their forefathers. As the oaths may have been sworn in front of an altar, or image (there was one to the Blessed Virgin Mary in St Edmund’s chapel) this election gave the civic authority sanction from God – jurats were in some sense divinely appointed too, adding sacrality to the customs of the town that had been performed ‘time out of mind’. The ceremony was possibly followed by a mass, a procession, and a feast. As Sheila Sweetinburgh summed up; St Leonard’s was a political as well as a sacred space symbolising the importance of the relationship between the town officers and the church in Hythe.

Church upper spaces and their uses by Toby Huitson

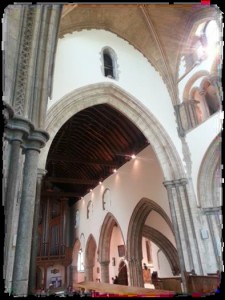

Although Toby Huitson’s paper concerned upper spaces in churches in general, it worked very well in adding context to St Leonard’s because this church has such a wealth of glorious upper spaces, such as the tower, the porch, the galleries, and wall passages, and still bears evidence of other upper areas which are no longer extant, such as the rood loft. Toby also briefly ran through the functions of each upper space using examples not only from Hythe but other English churches too – not all of which would spring readily to mind.

Although Toby Huitson’s paper concerned upper spaces in churches in general, it worked very well in adding context to St Leonard’s because this church has such a wealth of glorious upper spaces, such as the tower, the porch, the galleries, and wall passages, and still bears evidence of other upper areas which are no longer extant, such as the rood loft. Toby also briefly ran through the functions of each upper space using examples not only from Hythe but other English churches too – not all of which would spring readily to mind.

Towers

For example, a tower was chiefly to house bells. The Hythe churchwardens’ accounts for 1413 mention 5 1/2d for greasing the bells. However, the fabric of the tower cannot be used as evidence for medieval practices since it was rebuilt in 1750s, after it fell down on 24th April, 1749, possibly as a result of earthquake damage sustained in 1580. Towers were also used for clocks from the fourteenth century although Elham records mention an orologium in 1290. Churchwardens’ accounts for Hythe in c.1481 note the expenses for repairing the clock and making the ‘chyme’ as 48s/10d. Other uses included dovecotes in Sarnesfield, Herefordshire and even tightrope walking at Durham.

Porch Chambers

These are the rooms or lofts built above some porches generally in high status late medieval churches, some have two such as Chilham in Kent. The functions of these rooms are poorly recorded, but occasionally they might be used by a nightwatchman, for example in 1481 when the belfry, the clock and the organ were all being repaired. There were also used as vestries and sacristies, as at Walberswick where the priest’s vestments were kept in the loft over the porch in 1492. It was sometimes used to store books and documents too – i.e. a secure muniments room, also used by parishioners, as in Outwell, where Nicholas Beaupre’s will stipulated his wooden chest be set over the porch. More actively, the porch chamber was used as a schoolroom in Saffron Walden in 1513, and even as a dovecote in Hawkinge. The porch chamber at Hythe is a well-lit space so may have had various uses.

1492. It was sometimes used to store books and documents too – i.e. a secure muniments room, also used by parishioners, as in Outwell, where Nicholas Beaupre’s will stipulated his wooden chest be set over the porch. More actively, the porch chamber was used as a schoolroom in Saffron Walden in 1513, and even as a dovecote in Hawkinge. The porch chamber at Hythe is a well-lit space so may have had various uses.

Galleries and Wall spaces

It is are for a parish church to have three levels and a wall passage, but Hythe (not even a parish church but a chapel under Saltwood until the nineteenth century) has a clerestory, a triforium and a connecting wall passage accessed by a spiral staircase with a small but distinctive domed roof, which can be seen on the skyline above the north transept. Believed to be an iconographical copy of Canterbury cathedral quire, perhaps built by the same workers around 1200 (see Berg & Jones, Norman Churches in the Canterbury Diocese, 2009, p.106), the soaring chancel space was not finished until the nineteenth century. Toby did not speculate on why St Leonard’s has in effect a monastic style of chancel. It certainly made a fitting setting for the archbishops’ ordinations of priests (for example by Archbishop Pecham) and Hythe was close to the archiespicopal residence at Saltwood, sometimes used before travelling to the Continent. I, perhaps unwisely, speculate that this has connections to the martyrdom of Thomas Becket. The manor of Saltwood was taken briefly from Thomas Becket by Henry II and given to Ranulf de Broc but the king returned it to Becket in July 1170, amidst much ill-feeling – the de Brocs attacked the archbishop’s lands, occupied his churches, mutilated his horse and killed deer in his park, and were unsurprisingly excommunicated on Christmas Day, 1170. It was at Saltwood castle that Ranulf de Broc then met with the knights to plot against the archbishop on 28th December, the day before his martyrdom at their hands. Although Ranulph did not  participate in the murder, he was an instigator who went with them to the cathedral and returned to Saltwood with them afterwards. Could links to the martyrdom have led to the rebeautification of St Leonard’s in the late twelfth and early thirteenth century and explain why it was modelled on the Canterbury cathedral quire? Feel free to disagree with me. To return to the functions of the space, there is again no evidence for how it was intended to be used – and indeed Toby mentioned that some architectural historians regard these upper spaces as redundant. Other ideas assume that access was needed merely for maintenance. However, if liturgical performance is considered, especially in conjunction with the rood loft space, then these areas either lit by candlelight or lined with tapestries or draperies, or occasionally with a choir on feast days, the performative (that word again) aspects of the space might be inspiring. Toby’s film of the candlelit upper spaces showed a dramatic but soft up lighting – imagine the painted church, full of praise and incense, the five senses employed to turn the church into a vision of the celestial Jerusalem. The wall passage with its high window might have also allowed a single soloist to sing on high above the Rood Cross.

participate in the murder, he was an instigator who went with them to the cathedral and returned to Saltwood with them afterwards. Could links to the martyrdom have led to the rebeautification of St Leonard’s in the late twelfth and early thirteenth century and explain why it was modelled on the Canterbury cathedral quire? Feel free to disagree with me. To return to the functions of the space, there is again no evidence for how it was intended to be used – and indeed Toby mentioned that some architectural historians regard these upper spaces as redundant. Other ideas assume that access was needed merely for maintenance. However, if liturgical performance is considered, especially in conjunction with the rood loft space, then these areas either lit by candlelight or lined with tapestries or draperies, or occasionally with a choir on feast days, the performative (that word again) aspects of the space might be inspiring. Toby’s film of the candlelit upper spaces showed a dramatic but soft up lighting – imagine the painted church, full of praise and incense, the five senses employed to turn the church into a vision of the celestial Jerusalem. The wall passage with its high window might have also allowed a single soloist to sing on high above the Rood Cross.

Rood Lofts

Hythe has an internal spiral stair in the north transept pillar which gave access to the top of the rood screen. Most date from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries but this is very early, integral to the splendid chancel. Again Toby has managed to gather much from scattered documentary sources (which makes his new book so valuable) and thus we know that some rood screen  upper spaces housed organs, or were used for reading from the Gospel, for example the Passion narrative as happened in Wingham in 1544, before the processional cross was seized from the priest. Often the screen was draped with Lenten veils, or on feast days lit with candles, there is also sixteenth century reference to young girls sitting on pews on the rood screen.

upper spaces housed organs, or were used for reading from the Gospel, for example the Passion narrative as happened in Wingham in 1544, before the processional cross was seized from the priest. Often the screen was draped with Lenten veils, or on feast days lit with candles, there is also sixteenth century reference to young girls sitting on pews on the rood screen.

Masonry sculpture: Hythe’s carved stone fragments by Heather Newton

These two stimulating lectures were then followed by a trip outside for the third of the specialist talks, this time by Heather Newton, in charge of Canterbury Cathedral stonework. Heather had taken several examples of medieval stonework out to the sun-filled south side of the church. The pieces are usually stored in the ambulatory with the ossuary – that being such a relatively small space (and also it must be admitted one with more than a touch of Gothic horror about it) she had kindly carried up a dozen heavy exemplars to allow us to visualize Romanesque methods of masonry preparation and stonecarving.

Heather’s lecture was very detailed and fascinating as she explained how quickly and freely Romanesque masons worked using various sizes of adze, rather than a mallet and chisel which came in later. You can still trace the marks of the adze on the stone and Heather explained that this quick, natural style is very difficult for modern stonemasons to copy as they have been trained to work to perfection and much stricter parameters. Each piece was examined in turn so the change in methods of carving could be plotted over time, as the adze gave way to the mallet and chisel to enable more detailed relief work to be achieved. Many of the pieces were Caen stone, from Normandy, an excellent material for carving, with a beautiful rich colour. The last head, of local stone, was undated and something of a mystery is shown here, in case anyone can help date it.

Heather’s lecture was very detailed and fascinating as she explained how quickly and freely Romanesque masons worked using various sizes of adze, rather than a mallet and chisel which came in later. You can still trace the marks of the adze on the stone and Heather explained that this quick, natural style is very difficult for modern stonemasons to copy as they have been trained to work to perfection and much stricter parameters. Each piece was examined in turn so the change in methods of carving could be plotted over time, as the adze gave way to the mallet and chisel to enable more detailed relief work to be achieved. Many of the pieces were Caen stone, from Normandy, an excellent material for carving, with a beautiful rich colour. The last head, of local stone, was undated and something of a mystery is shown here, in case anyone can help date it.

Church tours by Imogen Corrigan and Andy Mills

The afternoon was taken up by tours of the church by Andy Mills, a structural engineer and Imogen Corrigan, a medievalist and expert on foliate heads – of which there is a perfect example in the Norman doorway which formed the entrance to St Edmund’s Chapel, although it may originally have been the west door of the Norman church. This splendid entrance to the chapel must have further enhanced the civic authority of the town’s jurats as this was where their elections were held. There was some discussion on whether the narrowness of the doorway  made it more Anglo-Saxon, as Andy discussed it may have been heightened at one stage, others thought it possible that there is a fusion of styles between those trained in Norman styles and those still using Anglo-Saxon ones, an overlap that can be found in Canterbury illuminated manuscripts of the same period. Asked if he would have built the church on this ancient landslip, Andy bluntly replied, ‘No!’ and showed how the Victorian roof masons in the chancel had had to achieve some difficult angles in their vaulting, perhaps evidence for some movement – as, of course, is the fact that the medieval church tower fell down in 1749. He then kindly led us down to the ambulatory where the ossuary now is, and invited us to look up at the beautiful medieval vaulting which I had failed to notice until he pointed it out, the 2,000 skulls and 8,000 bones being something of a distraction. These are believed to have been kept when the church was extended in the early thirteenth century.

made it more Anglo-Saxon, as Andy discussed it may have been heightened at one stage, others thought it possible that there is a fusion of styles between those trained in Norman styles and those still using Anglo-Saxon ones, an overlap that can be found in Canterbury illuminated manuscripts of the same period. Asked if he would have built the church on this ancient landslip, Andy bluntly replied, ‘No!’ and showed how the Victorian roof masons in the chancel had had to achieve some difficult angles in their vaulting, perhaps evidence for some movement – as, of course, is the fact that the medieval church tower fell down in 1749. He then kindly led us down to the ambulatory where the ossuary now is, and invited us to look up at the beautiful medieval vaulting which I had failed to notice until he pointed it out, the 2,000 skulls and 8,000 bones being something of a distraction. These are believed to have been kept when the church was extended in the early thirteenth century.

Little else is known about them although pinprick holes in the eye sockets of nearly 30% may indicate anaemia linked to malarial swamps. We then set about the documentary evidence with Jackie Davidson from the Cathedral Archives and Sheila Sweetinburgh who had kindly transcribed some of the wills and accounts while Jackie stood guard over the originals which were indeed wonderful to see. We spent a happy hour pouring over the evidence to build up a picture of lay piety in Hythe – Alice who left a gold ring to the statue of the Virgin Mary in St Edmund’s chapel, did her gift offer her not only a form of commemoration in the sacred space  but also meant her donation could witness the elevation of the Host not from the priest’s back but from the altar, something she would never have seen. Similarly John Honeywode’s burial, like that of his grandfather and later his brother, placed the family at the heart of this sacred-civic space, the interrelationship of the living and the dead through memory and commemoration providing continuity and a sense of stability.

but also meant her donation could witness the elevation of the Host not from the priest’s back but from the altar, something she would never have seen. Similarly John Honeywode’s burial, like that of his grandfather and later his brother, placed the family at the heart of this sacred-civic space, the interrelationship of the living and the dead through memory and commemoration providing continuity and a sense of stability.

This was a fantastic example of outreach and rigorous academic discussion, where documents complemented architecture and all gained from the learning experience.

For more information please refer to the KAS Churches Committee http://www.kentarchaeology.org.uk/churches-committee/