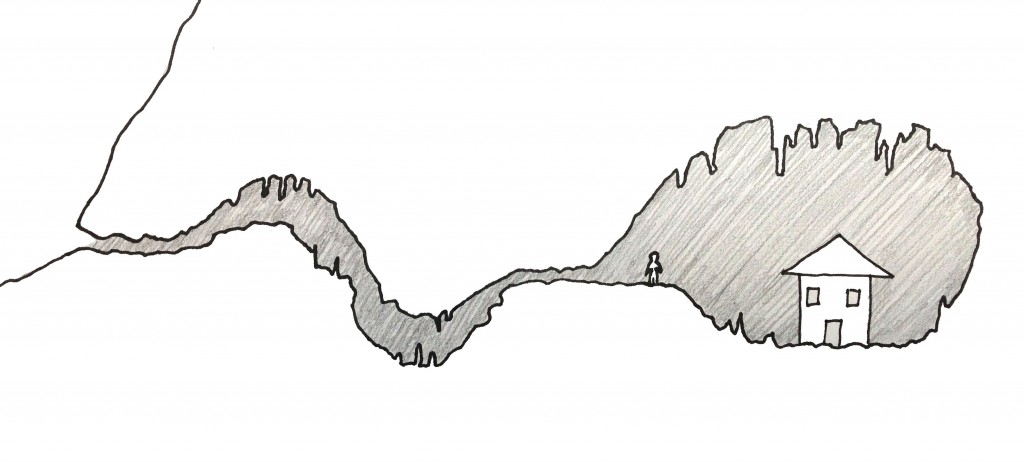

Many people believe that the origin of architecture has its roots in Marc-Antoine Laugier’s concept of the primitive hut. Two columns supporting a beam which in turn supports a pediment. However, in recent years, because of advances in sophisticated BIM software, I would argue that this is no longer the case as architects no longer have to restrict themselves to these basic construction techniques. As we progress forwards into the future, I believe that the forms that we construct should resemble a much earlier prehistoric concept, before the ‘caveman’ even built his primitive hut. Some of the most beautiful spaces in the world are only experienced by a select few who put in the effort to crawl on their bellies in order to reach them (believe me, I have done it), so why are these breathtaking forms not replicated in modern architecture? Well, you may be pleased to discover that as construction processes get more efficient, digging down is becoming more viable, and there are many current projects which utilize this hidden world beneath our feet, which you may not even be aware of.

Much in the same way as a cave system, part of the joy of underground architecture is the relatively humble external appearance. Many famous caves are entered through a single door in the side of a hill, which gives nothing away about what lies behind, an example of this being Kents Cavern, otherwise known as Britain’s oldest home. This concept has been transferred into the built environment in buildings like the Staedel Museum in Frankfurt. Hidden below the perfectly maintained lawn of the museum, the existence of this extension by German architects Schneider+Schumacher is given away only by a slight bulge in the centre of the lawn and the circular skylights which provide light for the pristinely white gallery below.

Although the Staedel Museum is discreet with its connection with the earth, other architects are not so subtle. For example the proposal for the Wadi Resort by Oppenheim Architecture & Design in Wadi Rum, Jordan is described by Dezeen.com as ‘setting forth a future primitive experience for the avid globetrotter’. The elemental nature of these 47 desert lodges is influenced by the history of the nearby ancient city of Nebataeans in Petra, carved from the rock itself.

There are many benefits to living underground, the predominant one being the climatic regulation and thermal mass it provides, which is greatly needed in hotter countries such as Jordan. A growing percentage of the population are jumping on the sustainable housing bandwagon, with many of these people choosing to submerge their houses below ground, for these environmental reasons. A housing typology known as earth-ships are becoming increasing popular, where the building is literally built using the earth which is excavated from the site, talk about low carbon footprint! Together with recycled materials and a creative flair, these homes can begin to resemble a village, or should I say ‘Shire’ from a certain popular fantasy saga.

Closer to home, and still on the topic of environmental awareness, the architecture firm Gensler has recently revealed its plans for the conversion of derelict underground tunnels into pedestrian and cycle routes around London. The diversion of pedestrians and cyclists away from the already crowded surface streets of London is not only safer, but makes choosing to cycle rather than taking a car a more attractive option, thereby reducing emissions and increasing air quality. Other proposal for cycle links around London have been proposed, the floating cycleways by the River Cycleway Consortium Ltd being a prominent example. However, London still has a way to go in order to reach the standards of cities like Amsterdam which retains its title as the worlds most cycle-friendly city in the Copenhagenize Index. In my opinion, London is right to utilize these unused tube tunnels, and should be looking into more ways to develop the city centre as a multi-level, multi-purpose transportation and cultural hub.

Budapest in Hungary is also making use of its underground ‘world’ clearly displayed in the new underground station by Spora Architects, currently still under construction. This cavernous space is reminiscent of some of the vast cave chambers which I have personally visited. The extensive use of concrete creates the similar grounded feeling which these caves also have, naturally. The only difference being the huge architectural beams which piece the vast void, necessary for pedestrian connective links and structural purposes, reminding me of some of Louis Kahn’s work.

Although this idea of burrowing back into the earth may seem like a recent one, I personally see it as a step back to the true elementary origin of the human shelter, although I am sure Laugier would disagree.

By Edward Powe – Stage 2 BA (Hons) Architecture