From 13 to 16 April 2016, I attended the Southeast Asian Studies Symposium 2016 at Oxford along with two other LLM students, Nik and Jodie (look out for their blog posts too!). The symposium was a wonderful opportunity to meet academics, government officials, activists and practitioners all specialised in Southeast Asia. I was part of a roundtable titled ‘The Rohingya: A Question of Citizenship and Identity’ which was well-attended by many people who had experience in Myanmar at different times. I also attended some really wonderful workshops, including one on financial inclusion and empowerment of women and girls, where I had the chance to talk to someone from the Cherie Blair Foundation about the need to change financial laws and banking practices in recognition of the specific challenges women face when it comes to accessing finance.

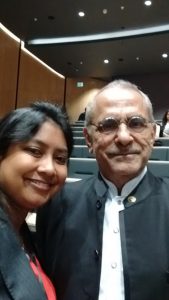

The keynote address at the opening plenary this year was given by former Nobel Peace Prize Laureate and former President of Timor-Leste, José Ramos-Horta. He began quite humorously, talking about his time at St Antony’s College in the 1980s, which he chiefly remembered for its very bad food. He claimed that he hardly ever ate the food, as it was ‘the worst’ and often passed his share to other students. This system left him with a standing bill owed to St Antony’s, which he was sent notice of with regularity for ten years, as it incrementally increased. It didn’t matter that he had become a head of state in that time.

The keynote address at the opening plenary this year was given by former Nobel Peace Prize Laureate and former President of Timor-Leste, José Ramos-Horta. He began quite humorously, talking about his time at St Antony’s College in the 1980s, which he chiefly remembered for its very bad food. He claimed that he hardly ever ate the food, as it was ‘the worst’ and often passed his share to other students. This system left him with a standing bill owed to St Antony’s, which he was sent notice of with regularity for ten years, as it incrementally increased. It didn’t matter that he had become a head of state in that time.

Dr Ramos-Horta then talked about how important Asia is as a region: home to over half of the world, it has the largest standing armies and some of the longest border disputes. He made a quick reference to the situation in Kashmir, which he described as the ‘most dangerous place in the world’.

Some countries, he said, had still not recovered from colonial occupation, and it remains a part of their national identity. Dr Ramos-Horta flagged the issue of violence against women and discrimination against women and girls, who endure acid throwing, are married off young or even sold off, and in some places face stoning for adultery. He underlined how essential girls’ right to education is to changing some of this.

Some countries, he said, had still not recovered from colonial occupation, and it remains a part of their national identity. Dr Ramos-Horta flagged the issue of violence against women and discrimination against women and girls, who endure acid throwing, are married off young or even sold off, and in some places face stoning for adultery. He underlined how essential girls’ right to education is to changing some of this.

Dr Ramos-Horta commented on Timor-Leste’s experiences and how other Southeast Asian nations might learn from them. Observing the corrupting effect of money on Timor-Leste’s 2007 elections, he jokingly said it was not clear whether in 2001 and 2002 whether Timor-Leste was more honest or did just not have enough money to influence elections, humorously terming this the ‘Asian style of democracy’.

Looking back on 40 years, Dr Ramos-Horta said there had been gains, although poverty is on the rise, while ‘democracy, good governance, and transparency are deficient’. He warned that it was vital for Asian governments to be more open and to listen to their people. The extreme violence experienced in some countries is often explained in terms of religion, but in reality this is an extremist ideology pervading in places. He commented that Myanmar is at the beginning of a difficult transition, like Indonesia after Suharto, and gave support to Aung San Suu Kyi, who he said needs time and space. Countering criticisms made about her, Dr Ramos-Horta said she was being judged too soon, and that it is hard to build a modern nation state.

Looking back on 40 years, Dr Ramos-Horta said there had been gains, although poverty is on the rise, while ‘democracy, good governance, and transparency are deficient’. He warned that it was vital for Asian governments to be more open and to listen to their people. The extreme violence experienced in some countries is often explained in terms of religion, but in reality this is an extremist ideology pervading in places. He commented that Myanmar is at the beginning of a difficult transition, like Indonesia after Suharto, and gave support to Aung San Suu Kyi, who he said needs time and space. Countering criticisms made about her, Dr Ramos-Horta said she was being judged too soon, and that it is hard to build a modern nation state.

In relation to Myanmar, but also to other Southeast Asian nations that have painful histories, such as Borneo, Indonesia, and Cambodia, Dr Ramos-Horta highlighted the importance of truth and reconciliation. He said that there was a need for an institute of memory, recognition of victims, and above all a process of remembering and reconciling with the past. This, he said, required a pedagogy of non-violence and forgiveness, warning that it is tragic to allow hatred. The challenge is how to present truth and reconciliation to the next generation, teaching non-violence not by omission, and without resurrecting anger. He said that the 21st century is Asia’s century, and it will see great challenges and great possibility.

His approach to history, truth and reconciliation was particularly stimulating to me, as I could place some of his positions with what I had studied in international criminal law, regarding war crimes and the role of trials and truth commissions. It reminded me of the role law can play in establishing history, and Martti Koskenniemi’s suggestion that war crimes trials are ‘less about judging a person than about establishing the truth of events’.[1] With over 300 people present, many from various Southeast Asian nations, Dr Ramos-Horta spoke on many relevant subjects for a large member of the audience, and provoked interesting discussions afterwards.

Sanam Amin

[1] Koskenniemi, Martti. ‘Between Impunity and Show Trials’. Max Planck Yearbook of United Nations Law, 6, 1, 1-32(32) 2002.