The medical team was calm, thorough and efficient. Repeated queries about my identity, a large arrow on my left arm pointing toward my hand and the two ‘x’ marks on the fingernails of my middle and ring finger helped to ensure the correct person, arm and digits went under the knife. The anaesthesiologist and the surgeon identified themselves and explained what they were planning. All concerns and doubts about the surgery and outcome were clearly outlined. Did I still wish to proceed? I did.

The surgery went well. In the general anaesthetic post-op fog I was wheeled back to the day ward. The surgeon loomed into view, gave me a serious and determined look, raised his hand into a fist and vigorously motioned the necessity for me to work very hard at exercising the fingers. I think I nodded.

A short two days later the plaster and bandages were removed exposing the neat twin cut lines of stitches zigzagging their way from palm along stiff and swollen fingers to ‘x’ marked fingertips. The work was beautiful. The therapist said 100% range of motion had been achieved under anaesthetic. She repeated the surgeon’s hand signal, took me through the exercises and said; now the work was to begin. There was no time to reflect. There was only time to work. Let pain be your guide, she said.

That was just over six weeks ago. Today is Good Friday. It has always been one of my favourite days. The relationship between what’s good and the sacrifice and suffering that accompany it remains of interest. But it was the seriousness of the occasion that impressed us children. Between the hours of noon and three the house was quiet. We were required to spend those three hours in silence, reading, reflecting or generally maintaining a serious countenance away from one another. One lucky child was allowed to ‘read’ the family bible, an impossibly large tome with leather cover, gold gilded pages and the sacramental details of relations past and present written in with spaces left for future inscriptions. An especially fidgety child might be given chores to complete or help hang laundry, but ultra smugness was reserved for those of us who managed to stay the course without flinching.

When we were old enough we were allowed to troop to church to learn the official, ritualised ‘by the book’ sadness. The heady combination of hours of fasting, solemn statues covered in purple cloth, Stations of the Cross, Gregorian chant and the ever thickening fog of incense had us hooked. By partaking in the ritual, we became part of an older tradition bigger than anything we could understand. Although the tradition spoke of sacrifice and sorrow, we simply aimed to kneel in stillness and silence for the entire time and in the end to offer our own superior suffering up to God. Boasting about the success of our suffering was not part of the official church ritual, but that did not stop us from scoring sacrifice points amongst ourselves.

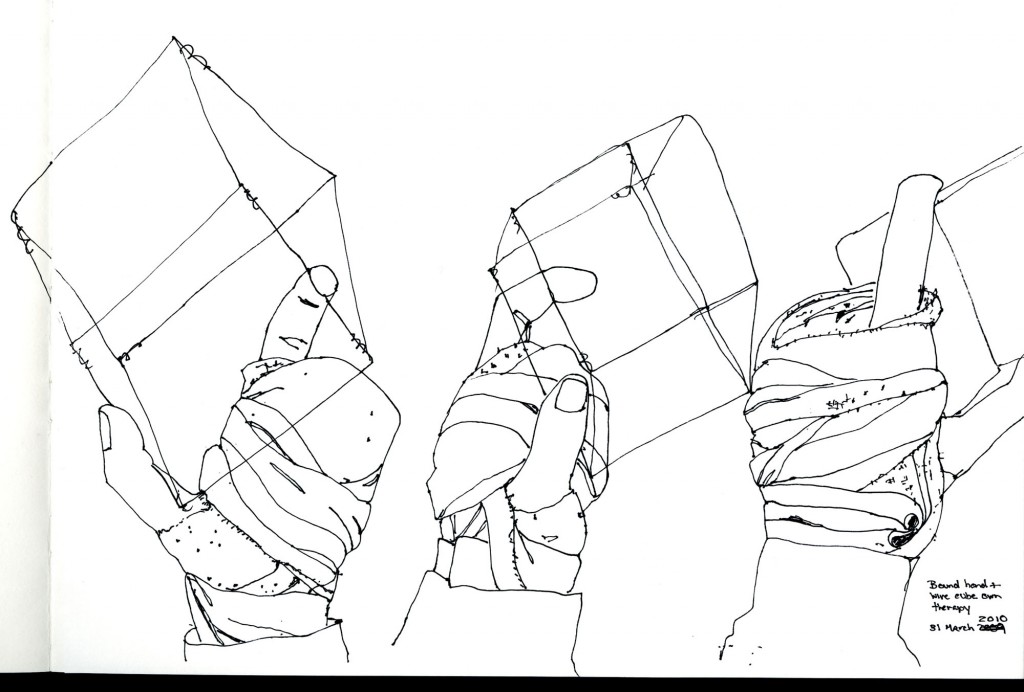

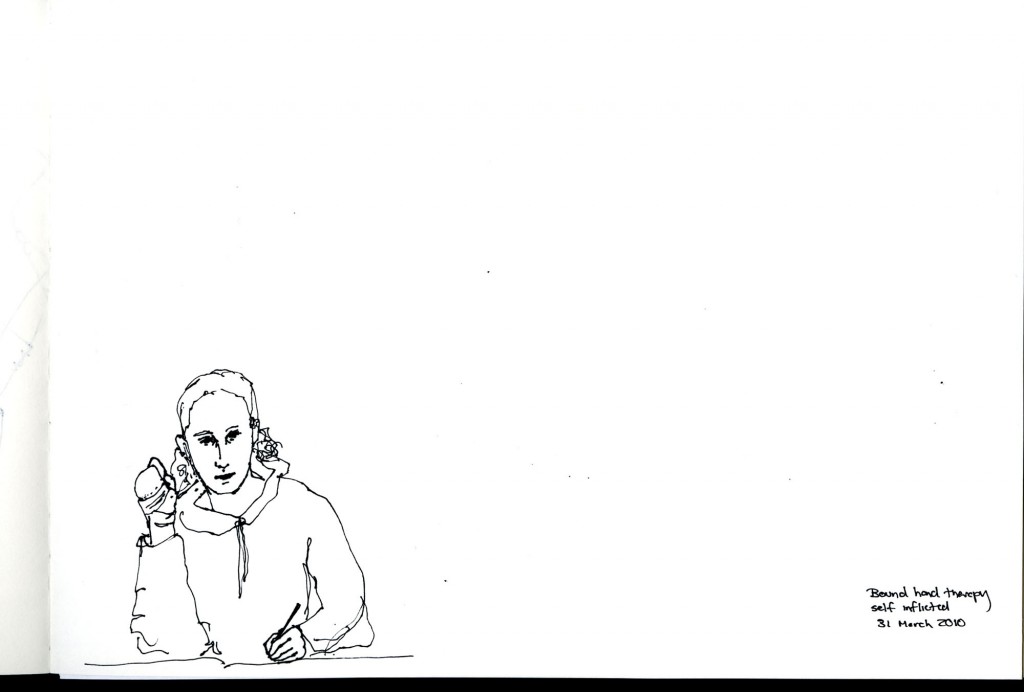

In the drawings from last year, a hand is bound, wrapped in a bandage designed to force fingers to bend. There is no pain in the drawing. The simplicity and looseness of the drawing belies the tightness of the binding and the pain inflicted underneath. The caption describes the therapy as self inflicted yet the face does not reveal pain.

Post op the exercises for my hand are repeated like breath. My aim is to improve the range of motion by five degrees each week. The final few degrees are proving the most difficult. At this stage, the pain of improvement is greater than before with less reward. Yet, the improvements are there. It is indeed a very Good Friday.