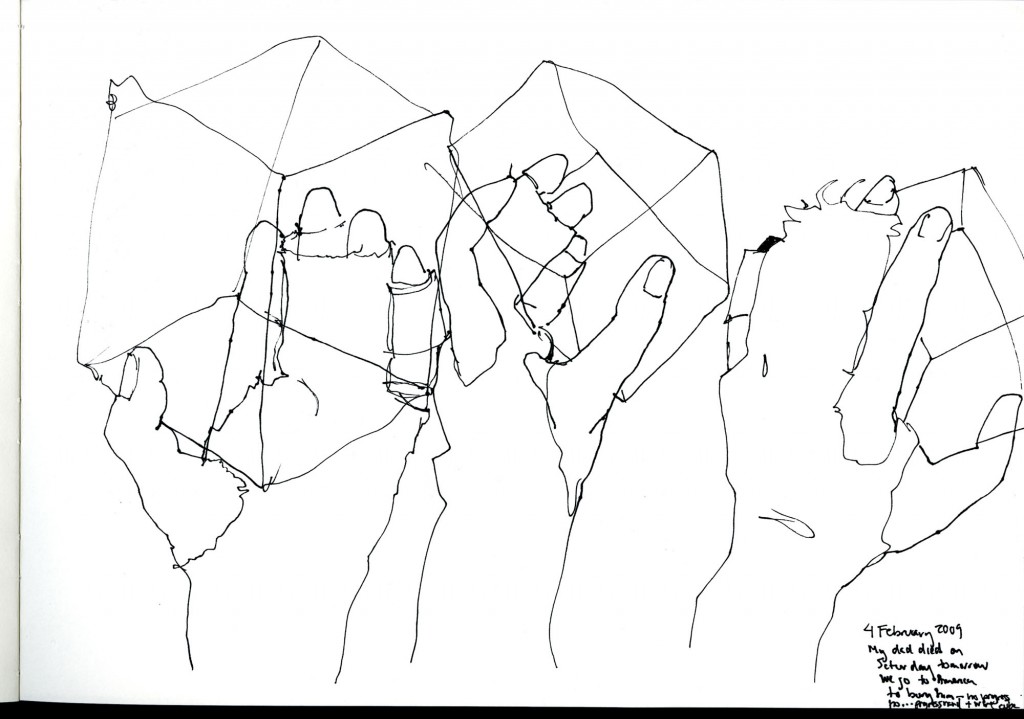

4 February 2010 My dad died on Saturday tomorrow we go to America to bury him no progress...no...progresshand + wire cube

It was a year ago today the accident happened. As in other areas of life, it is a time for review. A time to look over the past year and evaluate what has changed what needs keeping and what needs challenging.

A year ago the ordinary world was as expected, on the surface nothing seemed on the brink of change, the bright autumn sun shone on councils spending money they did not quite have, bankers made money, deficits grew, leaves fell in the crisp air, we were unpacking office things from the car, the garage door hinge had not yet crushed my fingers and across the world my father was still alive.

Aunt had said, “If you can handle loss, you can handle life”. Even though loss can come suddenly or slowly, randomly or relentlessly, it still seems a tough trickster sticking pins in our balloons, bursting our life bubbles. Perhaps we never look for it. Perhaps we do not want to see what is coming.

The night of the accident, in the emergency room, the kind medic dressing my hand apologised for the loss of blood. “There’s not usually this much”, he said. He was looking. Everyone else was looking too. I wasn’t. Unlike the calm look on the medics’ faces it was apparent on the others’ that there was something very wrong with my fingers. I asked my husband to please stop looking like that. I did not want to see my damaged fingers reflected on his face too. He kept looking, blessedly masking the mirror and adopting the medics’ look.

In the past we children would pull faces when the milk seemed off. A face forced sour by a sip of bad milk was met with a frown and the ultimate adjudicator’s test which was inevitably followed by the declaration “There’s nothing wrong with that milk”. We were expected to do as we were told, clear our plates, and avoid waste. Thus we were condemned to swallow life’s hard lessons; either we were right, the milk was sour and Dad was an harsh and brutal overlord or we could not trust our taste buds and Dad’s cast iron constitution and ruthless decision were right. To appreciate things like smoking cigars or drinking adult beverages or so many others of life’s joys and trials, we would have to pull in our belts, hold our noses and acquire the stomach for it.

Never mind the milk seemed thicker than it should be, the bananas browner, cheese greener, bread mouldier. Waste of any kind, curdled or otherwise, was simply not tolerated. It wasn’t that the meatballs always had giblets in them. Dad’s Sunday spaghettis were simply a product of leftovers emptied from the fridge. Woe betide the child who dared to prod a suspicious looking meatball with “Are there any chicken ‘parts’ in these?”. To which the inevitable reply was “No, no parts, it’s all good. There’s nothing wrong with those meatballs. Just eat them”. Trust eroded over time when we realised Dad’s idea of ‘no parts’ or ‘nothing wrong’ in the real world meant some possibility of an anomaly but not enough to count in his cookbook. Whatever state of decay food was in or however odd it seemed to us children, mould could be cut off, overripe bananas used for bread, wilted greens added to soup and chicken innards served as source for meatballs and sauce. We were fed and at times fearful but we ate well and survived.

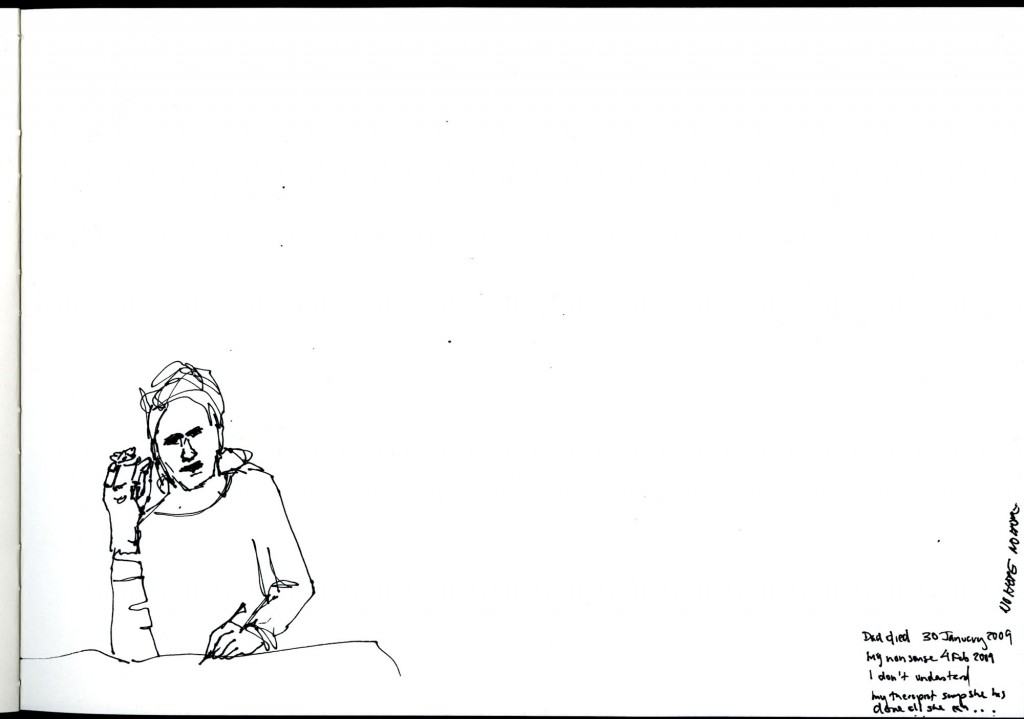

Dad died 30 January 2010 My nonsense 4 Feb 2010 I don't understand my therapist says she has done all she can...

Last January I was discouraged by what felt like a lack of progress. The fingers just did not seem to be moving enough. The patient’s effort was there. The therapist’s skill applied. Perhaps it was the dark days of January wearing me down. I felt a failure, embarrassed by the fingers that did not work and looked so odd. My husband could read my disappointment. “Let me see those fingers”, he said reaching for my damaged hand. He held it in his, turning it over, palm up, palm down, tracing the shape of each digit, looking at the fingers, massaging the scars. Then, with great care and tenderness he brought the fingers to his lips and kissed each gently, looked at me and said, “You know, there’s nothing wrong with those fingers”.

The winter solstice has always been my favourite day. We were married on that day of darkness, the long night turning toward the light. According to a calendar I invented for myself winter ends six weeks after the solstice. It is then that the most difficult season is over and spring offers light and hope. It was late last January and the snowdrops had just appeared as a sign of that hope. And although the last week of winter offered up hope and snowdrops, it also made its strength and harshness felt by claiming my father.

In the drawings made later that week, the lines are shaky and lost. The fingers barely hold a mess of broken lines meant to be a cube. Haphazard marks suffer from a lack of commitment, dismissed by doubt and death.

A year on, there’s nothing wrong with the natural order of things. An accident happened. My father died. One would think these losses would concentrate the mind. That one would learn to adjust. But time and change happen swiftly and slowly. This fast year on I still treat the drawings and life as if there is all the time in the world left to make them into something.

A year on? I can’t believe it. Keep on drawing Julie. Love the sour milk and the mouldy cheese, sounds like my childhood. I’m still eating that stuff!