It’s not the pain I remember from the accident. Three other vivid reminders do remain from that October night: the terrifying sound, the sickening sensation and the shocking silence of passers-by. Autumn has always been my favourite time of year. I remember walking through the woods in northern Michigan, surrounded by a blaze of colour, the air crisp and fresh, dry autumn twigs snapping underfoot. As children we tried to walk like Indians, respectful and silent in the falling forest.

I remember the crackling of kindling igniting in the promising early heat of the cold season’s first fire, small twigs sparking and popping with an ancient energy that always sets a small world to right for the night. A first fire in the hearth as the late autumn cold begins to bite. A late fire at the lake watching the full moon rise. The comforting promise of bright sparks and the snapping sounds of wood burning.

My fingers sounded like that when they were breaking, crushed in the accident in the garage door. My husband said he could hear the sound from inside the house; first the squeal of the hinge, the whooshing weight of the heavy door and then that sound of twigs, twigs crunching and snapping only they were fingers crushed in the door, not twigs underfoot or in a fire.

I could not see what I had done. I could not look. I knew. My hand. My fingers. Everything stopped, my hand stuck, the door half closed. I cried for help in the dark. Two people were passing by at the end of the drive. “My hand. My fingers.” They looked me in the eye, saw the door, saw my plight, heard my cries and walked on, silent in the street.

With the fingers of my left hand crushed against the frame, trapped by the hinge, I pushed the door up and open with my right. But my left hand did not come away. My fingers were stuck to the frame. My right hand reached for the place where the fingers were attached to the garage. I felt the sticky dampness of a bloodied mess and carefully pried it from the frame. Left hand and fingers were peeled away from the door, then cradled by the right.

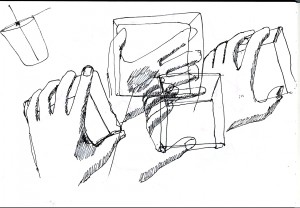

Earlier in the week I was trying to get my students to draw quickly from observation. I picked up a wire cube that had been part of another exercise. “Here, just draw them together, quickly. Don’t worry about accuracy now.” A hand, organic, a cube, geometric, mechanical. “Just draw,” I said, “quickly.”

My wedding ring is missing from my own quick sketch foreshadowing the accident later that week where a hand, organic, a door, mechanical would suddenly be drawn together too quickly and the kind medic would gently and carefully remove my ring from its torn and broken finger.

My husband and the emergency staff remained calm and kept my fingers and me together. I could not look. Hospital, surgery, home. The injury wasn’t painful but I could not sleep for the raw memory of the sound, the sensation and the silence.

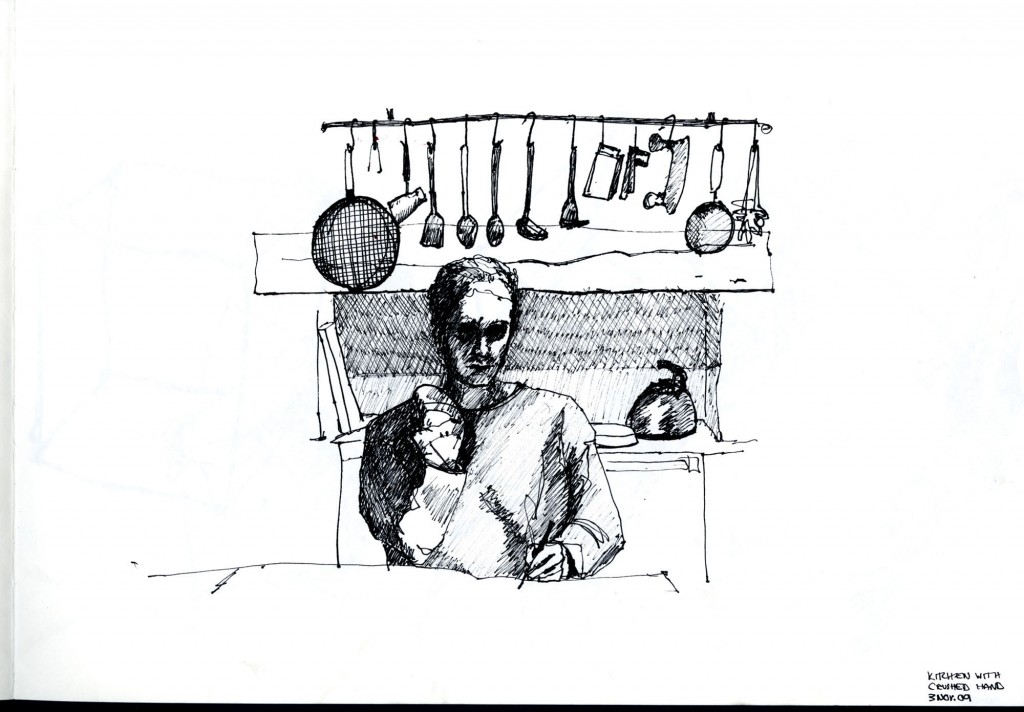

In the kitchen I began to draw, to do something normal. No more sculpture. Forget about that grade V piano exam. Look and just draw, quickly.

***

Coming up in the next blog: wire pins and hand grenades

The trouble with clients is that they want everything done for nothing yesterday.

Six months ago I quit my job as an architect.

The final job I was involved with had all the hallmarks of a classic refurbishment of a building. The client, a local educational institution, claimed a shortage of money and a tight schedule. The first claim is simply not true unless they are trying to do too much at one time…an early childhood lesson is: you can’t have the whole sweetshop with one week’s pocket money! The second is down to a lack of planning which you would think as educators they would have got their collective head around.

The building itself was of no architectural merit and was an ecological disaster. There was some sort of thermal insulation but it was very hard to find. In order to bring it up to code and save dumping tons of CO2 into the atmosphere over the next few years the client should have undertaken a comprehensive upgrade of all the thermal insulation and a careful analysis of the best long term plan for heating and cooling.

This was, they said, too expensive although they would have saved money in the long term. We tried to convince them that this was not the right move, but to no avail.

You cannot lock people up for ecocrimes…yet…Bye bye planet.

Anyway I quit…I’ve got better things to do with my life than to be told what to do by idiots. It just gets old.

On my last day I went for a quick drink with my friend David (Yeah I do have real flesh and blood friends) after work. Then I cleared my desk and drove home where Julie was waiting. We had agreed to go out to dinner to celebrate the beginning of the rest of my life. I drove the car into the garage, unloaded my boxes of books and office rubbish, taking them down to my basement studio. I was down stairs with the last box when I heard a snapping noise like a breaking of sticks… thick ones at that. I heard Julie upstairs shouting ‘help’. I rushed up stairs and there she was with her left hand mashed in the steel bars of the up and over door mechanism…

The real drawings and story are above…

She still owes me that dinner!

How extraordinary.

I happened upon this blog on a day that I had been thinking and talking about you, Julie. It has been very warm, and the little house you cast for me last year is soft and smells faintly, but deliciously of my childhood. I have been picking it up and handing it around, so that it collects prints. I had an artist friend at the house who hadn’t seen it, so she and I were talking about it too. The day that I collected it, and the tomb that my husband has in his office, was one of the last days that I was at UCA.

Sometimes, it’s hard to know how to feel about how resilient and how fragile we are, and how the physical and emotional marry to drive us into yet another unknown future.

Clearly your lives, together and separately, are moving in new directions; Dan and I are in a similar situation.

Dan began having seizures back in the autumn, and was, four months later, diagnosed with epilepsy. By that point we were over the best and the worst of it. The worst, because we spent quite a bit of time messing about in hospitals, and there was a certain amount of concern involved; we had to give up the car and the wine, and my college place, and a portion of our workload. The best, because we spent lots of time together, assessed what we wanted from the second halves of our lives if his diagnosis turned out not to be terminal, and because we felt closer, even, than we had before, and we’ve been very close for a very long time.

Accidents happen, and our bodies let us down, but, nine months on, Dan is juggling drugs and making choices about enjoying euphoria at the expense of ever driving again; or feeling flat and dull, but being allowed on a train on his own. I am making choices too, about the kinds of jobs I want to undertaken, and how much more I want to work, on my own books, and on film projects with Dan. For now, through choice, and necessity, all of those choices involve being together all the time, and it’s a pleasure.

These are not difficult times, they are liberating. We are not confined by our disabilities we are enabled by them.

I know that I will finish my degree one day. I am drawing and painting a little, but without thinking very much about it. Thinking was never really a problem for me; exercising the muscles, working on the skills, even though it’s only for one day a week, is enough, right now, to keep me very content.

I’m really looking forward to reading this blog, and finding out how things have changed for you since the accident. I’m sure I’ll see a lot of parallels with our experiences.

Very best,

Nik Vincent

Perhaps we might hear more about dangerous and damaging architecture.