History student Mary Sullivan recently completed some research as part of our recent Beyond the Barricades Exhibition, which is bringing together artists from various nations, looking at different dimensions of a revolution by focusing on the concept of Barricade.

The Swing Riots

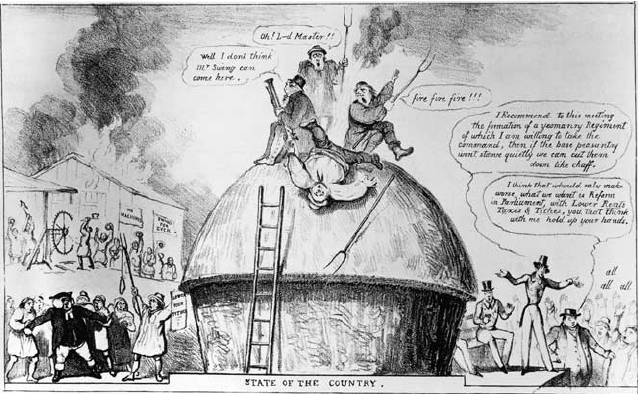

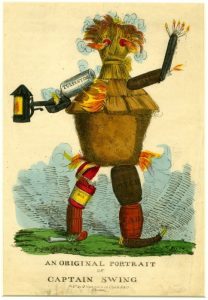

According to E. P. Thompson (1963), the wholesale enclosure of common land between 1760 and 1820 and the loss of the rights to cultivate it led to the impoverishment of the landless labourer, (especially in the south of England) who was left to ‘support the tenant-farmer, the landowner, and the tithes of the Church’.[1] However, poor harvests, low wages and high unemployment between 1829 and 1830, led to hunger among poor agricultural workers and their families. To add to their troubles, the Agricultural Revolution had introduced new technology such as the threshing machine which separated the grain from the stalks by beating it and thus dispensed with the need of workers to perform this task.  This situation resulted in protests that started in Kent and later spread to surrounding counties and further. They were called the Swing riots after the eponymous Captain Swing. The made-up name symbolised or represented the anger of the poor labourers in rural England who wanted a return to the pre-machine days when human labour was used. The threatening letters were sent to farmers and landowners which demanded that wages increase and which often told farmers to desist in their employment of threshing machines. Landowners and farmers also had their farm buildings and hayricks set alight.

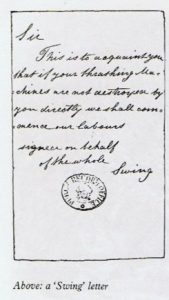

This situation resulted in protests that started in Kent and later spread to surrounding counties and further. They were called the Swing riots after the eponymous Captain Swing. The made-up name symbolised or represented the anger of the poor labourers in rural England who wanted a return to the pre-machine days when human labour was used. The threatening letters were sent to farmers and landowners which demanded that wages increase and which often told farmers to desist in their employment of threshing machines. Landowners and farmers also had their farm buildings and hayricks set alight.  According to Carl Griffin, who recently reassessed the origins of the disturbances in Kent, Swing first put his name to a threatening letter addressed to a farmer in Dover in early October 1830: ‘you are advised that if you doant put away your thrashing machine against Munday next you shall have a SWING’[2](on the gallows). According to Hobsbawm and Rude̒, the first of the Swing riots occurred on the night of the 28th May 1830, with the destruction of a threshing machine in Lower Hardres, near Canterbury.[3] Hobsbawm argued that in Kent, where the movement started and persisted the longest, there were five phases of action:

According to Carl Griffin, who recently reassessed the origins of the disturbances in Kent, Swing first put his name to a threatening letter addressed to a farmer in Dover in early October 1830: ‘you are advised that if you doant put away your thrashing machine against Munday next you shall have a SWING’[2](on the gallows). According to Hobsbawm and Rude̒, the first of the Swing riots occurred on the night of the 28th May 1830, with the destruction of a threshing machine in Lower Hardres, near Canterbury.[3] Hobsbawm argued that in Kent, where the movement started and persisted the longest, there were five phases of action:

- Fires in the north-west, reaching into the neighbouring county of Surrey.

- The wrecking of threshing machines in East-Kent around Dover, Sandwich and Canterbury.

- Late in October, wages meetings accompanied by /radical agitation against sinecures, rents and tithes around Maidstone.

- In early November, wages meetings and machine-breaking in West Kent, reaching the Sussex Weald.

- After mid-November, a further round of fires, tithe-riots and machine-breaking in East-Kent.[4]

At first, magistrates tried to be lenient with those arrested for offences committed during the riots, and in Canterbury at the East-Kent quarter sessions in October 1830, Sir Edward Knatchbull imposed a mere three-day prison sentence on seven machine-breakers[5]. However, as the uprising continued the penalties became more severe, and on Christmas Eve, 1830 William Packman, 20 years and Henry Packman, 18 years (convicted together with John Dyke [John Field]), at the Kent Winter Assizes in 1830, for arson on a barn belonging to William Wraight of Blean were hanged at Penenden Heath, Maidstone. A petition asking for clemency was rejected by Mr Justice Bosanquet of Maidstone who also dismissed the Jury recommendation for mercy.[6] Altogether 19 people were executed, 505 transported to Australia and 644 imprisoned.

The Battle of Bossenden Wood

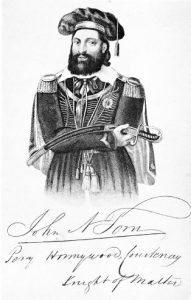

The Battle of Bossenden Wood took place some years later in 1838. It was instigated by John Tom, a maltster from Truro who turned up in Canterbury in 1832 posing as a Sir William Courtenay. He hoodwinked many people as to his true identity to the extent that he won votes in a parliamentary election in Canterbury. After a conviction for perjury, he was deemed insane and detained in the Barming Asylum in Maidstone in 1833. On release from the asylum, having lost his credibility in Canterbury, he settled for a while in the nearby village of Boughton and set about convincing the local people that he could rescue them from their poverty.[7] He quickly gained a following in Boughton and other villages in the vicinity such as Hernehill, and the Ville of Dunkirk. He impressed people with his knowledge of the Bible, convinced them he was the Messiah and preached a millenarian message. Millenarianism is a belief in a second advent bringing a destructive end to the sinful world and an ensuing thousand-year period of divine rule and felicity on earth.  As J. F. C. Harrison explained, ‘millenarians did not accept the culturally dominant conception of reality but inhabited a distinctive world of their own. In this (largely traditional) world, madness was explained in terms of supernatural intervention’[8] thus it was easy for Courtenay to persuade poor agricultural workers who disregarded his history of mental instability to follow him in revolt against the system. There had been previous agrarian discontent in that area during the Swing riots and further protests against the Poor Law of 1834. Farm labourers smallholders and some local tradespeople were quick to respond to his promises of a better life. On May 29th, Oakapple day, Courtenay led his followers on a march around the local countryside with a flag and the traditional symbol of protest – bread on a pole. The local landowners became concerned, and a warrant for Courtenay’s arrest was issued. When a constable and his assistant, Nicholas Mears attempted to arrest him, Courtenay shot dead Mears, and after that, the army was called in to intervene.

As J. F. C. Harrison explained, ‘millenarians did not accept the culturally dominant conception of reality but inhabited a distinctive world of their own. In this (largely traditional) world, madness was explained in terms of supernatural intervention’[8] thus it was easy for Courtenay to persuade poor agricultural workers who disregarded his history of mental instability to follow him in revolt against the system. There had been previous agrarian discontent in that area during the Swing riots and further protests against the Poor Law of 1834. Farm labourers smallholders and some local tradespeople were quick to respond to his promises of a better life. On May 29th, Oakapple day, Courtenay led his followers on a march around the local countryside with a flag and the traditional symbol of protest – bread on a pole. The local landowners became concerned, and a warrant for Courtenay’s arrest was issued. When a constable and his assistant, Nicholas Mears attempted to arrest him, Courtenay shot dead Mears, and after that, the army was called in to intervene.

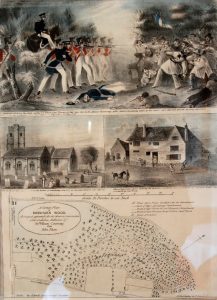

In Bossenden wood on the afternoon of the 31 May 1838, a group of about forty agricultural labourers were confronted and outnumbered by an armed detachment of the 45th Infantry Regiment, the constabulary and some of the local landed gentry. The armed forces quickly subdued the farm workers who only had sticks and staves to protect themselves apart from Sir William Courtenay, who was armed with pistols and a sword. He killed Lieutenant Bennett of the 45th Infantry Regiment. Courtney and ten others were killed by the soldiers.

About thirty of Courtenay’s followers were arrested. Ten of them eventually stood trial at Maidstone Assizes in August while the grand jury discharged the others. Two (Thomas Mears and William Price) were charged with the murder of Nicholas Mears and nine others with the murder of Lieutenant Bennett.

Thomas Mears and William Price were found guilty and sentenced to death, but a recommendation for mercy by the jury persuaded the judge, Lord Denman to reduce the sentence to transportation to Australia for life for Mears and Price for ten years. The rest were sentenced to ten years imprisonment.

Barry Reay argued that the Battle of Bossenden Woods in 1838 was one of the popular riots of the era (such as the Luddite riots, the Swing riots the Chartist campaign and the Tolpuddle Martyrs). Reay maintained that this battle and not the Swing riots deserve the designation of ‘the last rising of the agricultural labourers’.[9]

[1] E. P Thompson, The Making Of The English Working Class, 3rd edn (London: Penguin Books, 1980), p. 184.

[2] Carl J Griffin, “Affecting Violence: Language, Gesture & Performance In Early Nineteenth Century English Popular Protest’’”, Historical Geography, 36 (2008), 155.

[3] E. J Hobsbawm and George F. E Rudé, Captain Swing, 2nd edn (London: Phoenix Press, 2001), p. 97.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid, p.101

[6] “1 Collective Petition (12 People, From Maidstone (Parish Of Saints Cosmos And Damian). The National Archives”, Discovery.Nationalarchives.Gov.Uk, 2018 <http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C10340492> [Accessed 16 August 2018].

[7] Philip George Rogers, Battle In Bossenden Wood (London: Oxford University Press, 1961), p. 85.

[9] Barry Reay, “The Last Rising Of The Agricultural Labourers: The Battle In Bossenden Wood, 1838”, History Workshop, 26.1 (1988), 79-101.