In 1926 the British government launched a new initiative to stimulate the economy of the empire and encourage a sense of solidarity in the Britannic world. Although short-lived (it was wound-up in 1933), the Empire Marketing Board was a remarkable instrument of propaganda and persuasion. Designed to shape public opinion, the EMB drew upon the lessons the First World War had taught on the art of mass communication. Chief among the EMB’s tools was the poster.

Commissioning leading commercial artists, the EMB produced a truly remarkable range of posters. Visually arresting, some boldly modernist, others more traditional, all were eye-catching and demanded attention. Among the output were many referring to Africa and Africans. Studying those posters, their visual and written messages, reveals much about British perceptions of Africa and race. As posters designed primarily for display in Britain, they reflected ‘a white gaze’ and white views of the world. As instruments of those in power, the posters reflected the official view that the Empire was a family, but like all families, it had seniors and juniors, and thus emphasised rank and hierarchy. Within this worldview, Africans were part of the family, but their position was one of dependence upon the white rulers. The visual tropes then implied a happy relationship of trust, confidence and assurance between the two. Economic prosperity, and with it happiness, for all was guaranteed by this relationship, or so the EMB proclaimed. Of course, the realities on the ground were a long way from such cosy visions.

What was never in doubt according to the publicity campaigns was the value of African colonies to the empire: the African colonies and their peoples were to be lauded and celebrated. Typifying this approach was E. McKnight Kauffer’s striking series titled ‘One Third of the Empire is in the Tropics’, which was launched in the autumn of 1927. Designed as a triptych of panels, the central poster stated, ‘Jungles To-Day are Gold Mines Tomorrow’ and contained a table showing the balance of trade figures between the UK and its African colonies. The bottom banner then stressed the importance not just of imports from Africa, but how Africans were important customers for British-made goods, ‘Growing Markets For Our Good’. Dominated by vibrant shades of green, gold and yellow, McKnight Kauffer played upon cliches of ‘The Tropics’, its human populations and natural environment. It is clear that although very much a modernist artist, McKnight Kauffer drew upon a deep well of received images and stereotypes. His poster then maintained the official view that the empire offered opportunity for all. The first panel related to cocoa production and showed three Africans, two men and one woman, at work. All three have very dark skin, ornamental bands on their upper arms and wear pink sarongs. In the final panel, depicting banana palms, there are three men, one of whom carries a pole from which a basket is slung. In the central panel, the figures flank the table of trading values. To the viewer’s left is a smiling woman holding a pineapple. She has gold jewellery, a brightly coloured sarong and a striped head-dress. The man also has a sarong, bracelets and a head-dress and carries a carved mace and shield. Such interpretations reinforced a particular view of Africa as people engaged with agriculture and rural life and their styles of clothing are ‘traditional’, implying that they live in a world under-developed according to British definitions of modernity. This sense of existing in a different time-space was underlined by the device of a sailing ship in a chevroned section of the central poster, which also implied a historic relationship with Britain going back over the centuries. An implicit part of the messages seems to be that Africans are people of the land and people of villages who benefit through Britain linking them to the wider, modern world.

McKnight Kauffer: ‘One Third of the Empire is in the Tropics’ and panels, ‘Cocoa’, ‘Jungles Today are Gold Mines Tomorrow’ and ‘Banana Palms’. Displayed: September-October 1927. TNA reference: CO 956/501.

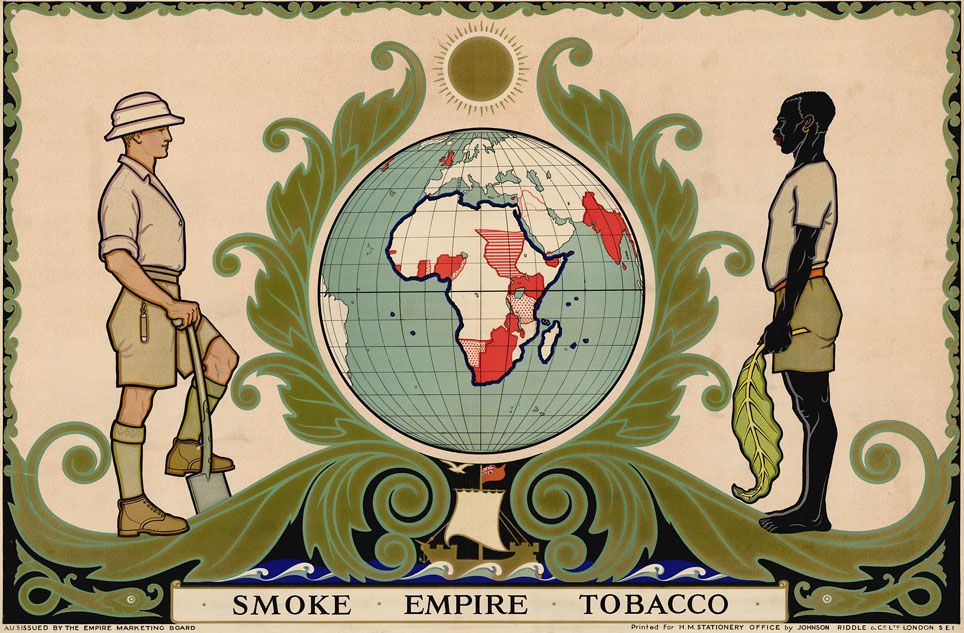

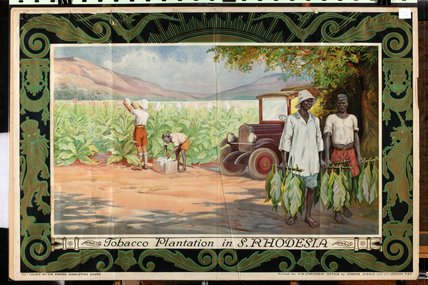

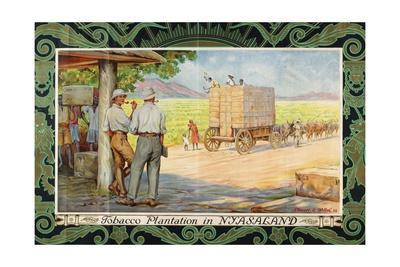

Far less strikingly modernist in artistic style, but with a similar theme, was Frank E. Pape’s triptych, ‘Smoke Empire Tobacco’ of the summer of 1929. The two flanking panels depicted tobacco plantations in Southern Rhodesia and Nyasaland (now Zimbabwe and Malawi respectively) with a central panel dominated by a map of the world focused on Africa with the British colonies in red. Once again the sailing ship image was used, this time in the decorative banner underneath the globe, while either side stand a white colonist and a black worker. In all three images, the impression is given of white settlers and black people working together in harmony, but with the white men clearly in control providing paternalist oversight. In the right hand panel, two white men stand smoking pipes (doubtless filled with local tobacco); they are talking while the black workers get on with the job. However, it is clearly a place of contentment. This is strongly implied by the background image of a waggon loaded with tobacco bales. Perched on top of the bales is a black worker raising his hat and leaning forward to speak to a woman on the road who is holding a child’s hand. It is obvious that a happy conversation is in progress and shows a world where all have a place and all are content with that place. The idea of a hierarchy is also emphasised by the central panel in which the colonist in stereotypical garb of khaki shorts, shirt, knee-length stockings and boots and a white solar-topee has a spade in his hand. Facing him, the unshod black labourer in equally smart khaki shorts and shirt holds a large tobacco leaf. As in all EMB posters, physical differences and characteristics were generalised and emphasised according to the prevalent ideas of racial structures. The power relationship is subtle but clear: the white man has the instruments of productivity in the spade, and he appears to have a whistle on a chain, thus implying that he blew instructions and signals to the workers. He is the person who recognised the opportunity and developed it, whereas the African is the person who assists in ensuring the outcome and the result of that input. The underlying, implicit message of the posters is that the natural resources of Africa are enhanced and focused thanks to white intervention, which, once again, reflected the views of those in power rather than the realities of the situation.

Frank E. Pape: ‘Smoke Empire Tobacco’ and panels, ‘Tobacco Plantation Rhodesia’, ‘Smoke Empire Tobacco’ and ‘Tobacco Plantation in Nyasaland’. Displayed: June 1929. TNA reference: CO 956/94.

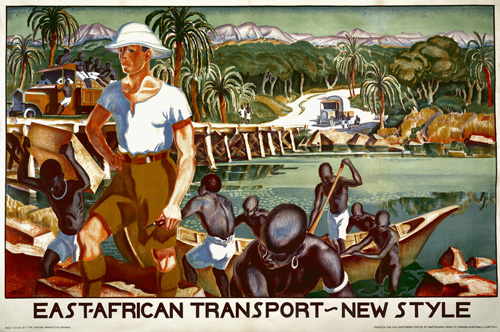

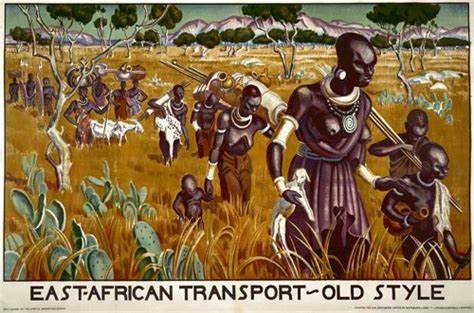

A similar theme can be seen in Adrian Allinson’s diptych, ‘Colonial Progress Brings Home Prosperity’. The two linked images illustrate ‘East African Transport Old Style’, which formed the left-hand panel, and ‘East African Transport New Style’. The old style panel shows a plain with mountains in the distance, which is, presumably, Kenya. The image is dominated by a trail of people in a diagonal column moving from the bottom right of the image to the top left. Bare-breasted women carry pots and bundles, one holds a small lamb in her right hand, all are ushering on children, many of whom also have bundles. The implication is of arduous trudging. By contrast, the new style panel shows a brand new bridge neatly constructed on wooden piles straddling a river. Modernity is further emphasised by the fact that a motor vehicle is about to cross. A sturdy boat is moored on the near side as packing cases are off-loaded by African workers. Dominating the image is a white settler clothed in khaki shorts, a white shirt and a white solar-topee. He stares out of the frame into the distance over the viewer’s shoulder in a manner that implies calm command and control over the entire scenario. This image was altered, as in the original the settler held a whip in his hand, which was then substituted for a pipe. Although the whip was meant to imply safety from the wild beasts of the region and did not seem to raise any concerns among many officials, the East African Trade Commissioner registered his concerns and requested an alteration. As someone more attuned to the local atmosphere, he was clearly much more sensitive to the implications of the image. For him, there was the very real concern that the whip might be perceived as a means of ensuring discipline among the workers. Anything hinting that the empire might not be a happy collaborative operation had to be suppressed. With the ambiguity removed for a symbol of calm dependability in the form of the pipe, the poster was able to proclaim British influence was a kindly, nurturing and supportive one. Africans flourished through British leadership, so it is claimed.

Adrian Allinson: ‘Colonial Progress Brings Home Prosperity’ and panels ‘East African Transport Old Style’ and ‘East African Transport New Style’. Displayed: December 1930-January 1931. TNA reference: CO 956/215.

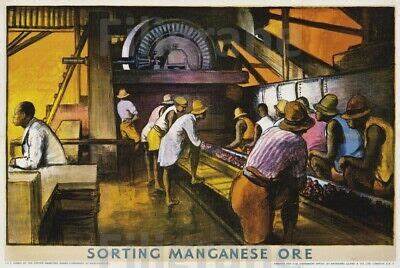

British development of inherent African potential was also seen in G. Spencer Pryse’s ‘What Gold Coast Prosperity Means’, first exhibited in the spring of 1928. Unlike the agricultural products of the other posters, this one focused on the results of large-scale mining and industrialisation. ‘Sorting Manganese Ore’ showed a conveyor belt carrying minerals in the foreground and the background dominated by the machinery of a winding mechanism. Either side of the conveyor belt stand black African male workers all of whom wear hats and coloured vests or shirts. Unlike the figures in ‘The Tropics’, these men are clearly involved in an industrial process with all its implications of modernity. To the left of the image a black man in a white jacket stares out of the frame. He is, perhaps, a foreman about to receive instructions or information from someone just beyond the realms of the image. Such a device seems to imply that the native people are given opportunities, which if grasped are recognised and rewarded with leadership roles and a higher status. And as the title of the poster suggests, Gold Coast prosperity is a two-way street: British industry gains a vital resource and Africans find enhancing employment opportunities.

G. Spencer Pryse: ‘What Gold Coast Prosperity Means/Sorting Manganese Ore’. Displayed: April 1928. TNA reference: CO 956/8

In examining just a few examples of the depiction of Africa and Africans in the EMB’s posters, the complex history of colonialism, its assumptions and stereotypes, its aims and ambitions can be detected. Black people are central to these images and they are depicted as active participants in, and beneficiaries of, the further development of the empire. However, the roles played and the degree of agency revealed were controlled and expressed by white rulers operating in London offices far from Africa and the realities of everyday life in Britain’s colonies.

Mark Connelly is head of the School of History at the University of Kent and a specialist in the cultural and military history of modern warfare.

Image Credit: McKnight Kauffer: ‘One Third of the Empire is in the Tropics’ and panels, ‘Cocoa’, ‘Jungles Today are Gold Mines Tomorrow’ and ‘Banana Palms’. Displayed: September-October 1927. TNA reference: CO 956/501. Licence: Non-Commercial Licence