Earlier this year, the School of History and the University of Kent’s History Society teamed up for a project to think about equality, diversity and inclusivity in our understanding of World War II, and to shed light in particular on allied spies whose efforts are often overlooked. According to the American Central Intelligence Agency, also known as the CIA, it wasn’t until 2019 that females were equally represented amongst their staff. In the United Kingdom, the MI5’s employee workforce reached a high of 47% women with women also making up 53.8% of their new employees. Historically, male spies have far outnumbered female spies, and even fewer of these female spies are women of colour. There was, however, diversity among the allied spies of World War II. Here we publish the results of this project, which comprise the biographies of four remarkable individuals, written by members of the School of History student community. These spies were far ahead of their time and overcame unique adversities; these extraordinary efforts and their perseverance deserve adequate recognition.

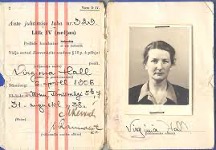

Virginia Hall (1906–1982)

Author: Madalyn Mann

Virginia Hall was born to a wealthy family from Baltimore, Maryland in 1906. After Hall attended college in the US, she left to study in Paris with the intention of becoming a diplomat. While in Paris she applied to work as a diplomat but was rejected. At the time, 99.6% of foreign officers were men but this didn’t deter her and instead took a job at the embassy in Poland and later Turkey. During a hunting excursion in Istanbul at the age of 27 Hall lost her foot in a tragic accident and was given a wooden leg. After recovering, she moved to work at the American legation in Estonia as Germany launched war on Poland in 1939. Hall continuously offered her efforts to the British army but was rejected yet again with prejudice due to her sex and disability. While driving ambulances across France she was spotted by an undercover allied agent in a Spanish train station who directed her to his “friend” in London, a senior officer in the British special operatives executives, or the SOE, who conducted espionage and reconnaissance. In desperate times, British forces finally gave Hall a chance and began training her in espionage in the south of England, serving as an American spy before the United States had even joined the war. Hall moved back to France and worked with sex workers who had contracted venereal disease (VD) and would drug German officers, photograph them in their uniforms and pass the information on to Hall after deliberately infecting them with VD. When various members of the SOE were tricked into attending a meeting in France and sentenced to prison, Hall began planning their prison break as they were tortured and awaited their execution. The SOE were moved to an internment camp where Hall recruited camp workers and a priest who shut down one of the security towers to sneak all 12 SOE members out. The Mauzac Prison break last 12 minutes, and the shocking story reached Hitler’s door who ordered a crackdown and flooded Northern France with Gestapo. Shortly after this Hall became the Gestapo’s most wanted target who posted wanted advertisements of her face that read “the enemies most dangerous spy, we must find and destroy her”. As her features became more and more familiar and allied forces landed troops across North Africa, Hall needed to disguise herself and escape France. In 1942, she began climbing across the Pyrenees with a guide, concealing her disability but was caught by the Spanish civil guard for 20 days until the American embassy secured her release. Desperate to volunteer her efforts in the war once more, she stained her white teeth, changed her attire and weight to disguise herself as a French peasant. Although Hall had no experience training resistance groups, in disguise she trained 500 men made up of veterinarians, schoolboys and book shop owners. They blew up bridges, cut telephone wires and are claimed to have killed over 150 Nazis without the help of a single professional soldier kickstarting the French resistance. Virginia Hall is arguably one of the most important American spies of all time and was the most highly decorated female civilian of her time and yet her efforts are often overlooked.

Josephine Baker (1906–1975)

Author: Lindsay McInally

When you think of spies you think of shadowy corners and secret meetings. You don’t think of a beautiful black theatre and movie star walking her cheetah along the streets of Paris or driving her luxurious Packard car through the city after a performance at her own club in Montmartre. Josephine Baker was a spy who hid not just in plain sight but in the spot light. Jacques Abtey, Baker’s handler, was unsure such a celebrated Parisian personality would make a suitable spy. He was won round, however, when he realised that Josephine Baker didn’t need to sneak into embassies and consulates in Paris; she was openly welcomed, enthusiastically invited and privy to unguarded, important conversations. Baker was free to travel, often with her animals including a Great Dane and a Golden Lion Tamarin, in the guise of planning upcoming tours. She used performances as cover for intelligence trips, actually smuggling information to Allied intelligence forces. Briefings and instructions were written in invisible ink on the pages of Baker’s music scores and she pinned photographs and notes into her underwear. Border guards were star struck, more interested in asking for autographs rather than strip searching the star. Her spying was spectacle and distraction, the perfect magic trick. Baker moved to her house in Southern, Vichy controlled, France in 1940 when the Nazis invaded Paris. Chateau des Milandes became a hiding place for Resistance members with Baker providing shelter and money. Eventually forced from France, Baker moved to Marrakech but her spying and support for the French Resistance continued. Hospitalised in Casablanca with sepsis, Baker turned her room into a secret meeting place and, with carefully considered invitations, continued her information gathering by quietly listening to the unguarded gossip about German agents and intelligence taking place at her bedside. After the liberation of France Josephine Baker, shocked by the conditions in her adopted city, sold her own jewellery, raising money to help war torn Parisians. General de Gaulle awarded Baker the Croix de Guerre, the Rosette de la Resistance and the Chevalier de Legion d’honneur.

Beatrice Temple (1907–1982)

Author: Niles Schilder

During the summer of 1940, everyone expected a German invasion. The British government had already seen what had happened to so many other countries before it and were determined not to be unprepared. Many safeguards were put in place and one of the most secret and most important was an underground army to conduct sabotage operations behind enemy lines known as Auxiliary Units. Such was the security of the organisation little is known about them; even less is known about their intelligence gathering subbranch commonly referred to as the Special Duties section. The Special Duties section was made of people from the community and would report vital information on the invasion back to the Auxiliary Units using radio and dead letter drops. The task of choosing these operatives from a shortlist was down to ATS officer Senior Commander Beatrice Temple. Temple was born on the 14th October 1907 in Bengal, India to English parents. Before the war Temple had toured Europe and was in Vienna during the German invasion of Austria and even saw Hitler in a parade while she was on her way to Italy. Upon returning to England, Temple joined the ATS hoping to become a driver. She was promoted, however, and she later said that “I had only five days to become an officer. I learned to drill with sergeants in the Guards, studied military law but mainly administrative work.” In November 1941 she was asked to command the Special Duties section with her office at Coleshill, Warwickshire. Temple interviewed candidates for Special Duties section agents at either the ATS Officers’ Club Hyde Park or at the tearoom in Harrods; this way Temple was able to judge if the candidates were able to conduct themselves with proper decorum and go without suspicion. Because most of the candidates were generally well educated and attractive, they became known as “Secret Sweeties”. The organisation was so secretive that after the war none of the members, not even Temple, received any recognition. Temple left the ATS in 1948. She later served on Lewis Borough Council and became the only woman alderman serving as Mayor in 1972-73. She died in 1982, having never revealed her role in what would have been Britain’s ninth secret service in the event of an invasion.

Violette Szabo (1921–1945)

Author: Bethany Parker

Whilst the details of Violette Szabo’s recruitment as a spy are vague, the impact she had during her servitude is very clear. Being the second woman to be awarded the George Cross for bravery speaks volumes about her impact, which deserves so much attention. Throughout her missions and capture she demonstrated unfailing resilience, never giving up sensitive information even during her SS interrogation, torture and time in various German concentration camps. Violette was a member of the special operations executive and much of her espionage work took place in France. During these missions she proved to be a useful asset to the organisation due to her ability to speak both French and English. Her solo investigation into the disappearance of a fellow SOE operative resulted in her collecting vital information on the production of German war materials. This information was irreplicable to the allies and enabled them to determine key bombing targets. Her legacy also lies in her impact on her fellow operatives and prisoners during her capture. She was described as an enthusiastic member of the SOE who inspired morale within the teams she was placed. Even after being captured and tortured, she remained resilient and led an interpretation of “Lambeth’s Walk” in a German concentration camp to show defiance and keep her fellow prisoners hopeful and morale high all the way up until her execution in 1945. Moreover, she, along with three of her fellow prisoner, took the opportunity during an allied attack on a prisoner transport train to gather water for the other captives. Violette Szabo was a selfless, resilient, and brave spy whose impact on the allies, SOE and fellow prisoners deserves to be recognised and her dedication and sacrifice remembered.