In celebration of Black History Month, staff and students in the School of History have been writing blogs about key figures in black history. Dr Emma Hanna, Lecturer in Modern British History, has written the following blog about pilot and musician John Jacob Niles.

During and immediately after the Great War there was a desire among the musically inclined to record the songs sung by servicemen during the conflict. We have British and French examples in the form of songbooks which sought to preserve the tunes sung in the trenches, on the march, in cockpits and aerodromes. Among those is Singing Soldiers by John J. Niles, (London & New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1927).

John Jacob Niles (1892-1980) was a composer, singer, and collector of traditional ballads. From 1917 he served in France with the American Expeditionary Force then as a pilot with the United States Air Service. Niles wanted to note down the songs sung by American servicemen. However, he was disappointed that the ‘white boys’ generally sung ready-made tunes from Broadway in which he was not interested, particularly as many of those songwriters had not joined up. Much more original to his ears were the songs of black soldiers who sang during whatever task they were performing, be it ‘marching, digging, cooking, travelling, unloading ships, or any of the thousand and one jobs soldiers always have to do.’

Approximately 200,000 black men served in the American Expeditionary Force and were deployed to Europe from 1917. Over half of those number were assigned to labour and stevedore battalions such as the African-American 369th Infantry Regiment who arrived at St. Nazaire in December 1917 before they were integrated for combat under French command in March 1918. Their regimental band was lauded as one of the finest in the entire Expeditionary Force, accredited by some as responsible for introducing France to Jazz music. However, Niles was most interested in the songs sung by the men as they laboured. He was taken by the ‘mellow, resonant vocal qualities’ of soldiers who he understood were singing these tunes ‘prompted by hunger, wounds, homesickness and the reaction to so many generations of suppression.’ Niles also found this ‘haunting’ folk music reminiscent of his childhood years in Kentucky.

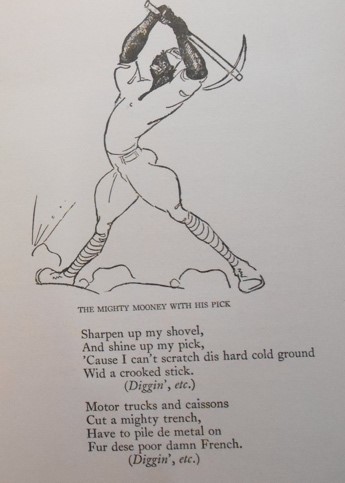

Singing Soldiers places the songs of black American soldiers in their wartime context. Niles’ anecdotes about his own war experiences are interspersed with the music and lyrics of the soldiers’ songs, accompanied by illustrations completed after the war by Margaret Thorniley Williamson. While the volume is written in the style and language of 100 years ago, it was intended as a testament to the wartime service and experience of those 200,000 black men who served and fought in the last stages of the world’s first total war. That the men took with them the songs of their forebears, and continued to compose their own melodies to help them through the experience of industrialised warfare was recognised and respected by Niles. He intended that Singing Soldiers – his ‘diary of soldier music’ – should show that the service and music of black men in the AEF ‘had some part in the success gained by our arms in the past war.’ While the work of these servicemen is not as visible as it should be in many histories of 1914-18, Singing Soldiers secured the essence of their wartime musical culture in perpetuity.