To celebrate International Women’s Day, members of the School of History present some of the astounding women from their research. They represent femininity, bravery, foresight and leadership.

Simone Veil, France, 1927-2017: Humanitarian and Activist (by Madalyn Mann, PhD student)

Simone Veil (pictured above) was born in Nice, France in 1927 and was deported and sent to the Auschwitz-Birkenau death camp and then to Bergen-Belsen after graduating with her baccalaureate. Although Veil’s brother and father died in the Holocaust, she went on to champion for women’s rights across France by serving as a Health Minister and facilitating access to contraception in 1967, and the legalization of abortion in 1975. Veil was also the first woman to serve as the President of the European Parliament from 1979 to 1982. Today we say thank you to Simone Veil, for all that you fought through and stood for.

“My demand as a woman is that my difference be taken into account so that I am not forced to adapt to a male model.” – Simone Veil, 1927-2017

Emma of Normandy, c.984–1052 (by Robert Gallagher, Lecturer in Early Medieval History)

Emma of Normandy (c.984–1052) is one of the most famous and extraordinary women of English medieval history, without whom the Norman Conquest of 1066 would probably never have happened. The reason for this is that Emma herself was Norman, and it was her marriage to the English king Æthelred the Unready (r.978–1016) that brought Normandy to the heart of English politics. Æthelred was not, however, the only English king that Emma married. After the conquest of England by the Scandinavian leader Cnut in 1016, she married this new king. Both of these marriages bore male heirs, which perhaps inevitably led to a succession crisis on the death of Cnut in 1035. As to Emma herself, her circumstances and actions were often conditioned by her gender, lacking the social agency that her male counterparts could wield. Nevertheless, she was a great survivor, outliving both of her husbands. What is more, without Emma we would know considerably less about the political events of the first half of the eleventh century, since she commissioned one of our key narrative sources for the period, an extaordinary Latin text known as the Encomium Emmae reginae (‘The Praise of Queen Emma’). It is this text that perhaps fascinates me most about Emma. As a researcher interested in multilingualism and uses of the classical past, it never ceases to amaze me that Emma responded to her own political circumstances in the early 1040s by commissioning a Latin historical narrative that compares her to a Roman emperor. It tells us a huge amount about the values of the eleventh century, and about how women could generate social capital within that world.

Dorotha Armpachová, Czechia, d.1600 (by Suzanna Ivanič, Lecturer in Early Modern History)

On her death, Dorotha Armpachová’s house and property were inventoried: a list of possessions was made to enter into the official town records. The archive reveals that – amongst sumptuous velvet clothing, kitchenware and books – she also owned nine pieces of chalcedony, an agnus dei and a small bottle with carnelian. The pieces of chalcedony are intriguing. They were thought to aid cheerfulness and drive away evil spirits, melancholy and sadness. Carnelian could prevent menstruation and miscarriage. Agnus dei were commonly thought to safeguard an unborn child. Is it possible that this coalescence of items gives us a glimpse into the emotional and physical stresses of life and childbirth in c.1600 in Prague? Did she suffer miscarriages and feel the great sadness that came with them? As historians, how much can we know about women like this and their experiences of life? What evidence do we have and how far can we take it?

Brigadier Mary Murray, Britain, 1863-1938 (by Emma Hanna, Lecturer in Modern British History)

Brigadier Murray worked in the Salvation Army’s women’s social work before she became secretary of their Naval and Military League. She served in the South African War in 1900, for which she was awarded the South African War Medal. On the outbreak of war in August 1914, Murray led a team to France to assist the British Expeditionary Force to assist in field hospitals. Murray was determined to be where the army needed help, regardless of the risks. She was at the battle of the Aisne in September 1914 where she was ‘slightly burnt’ by a shell. By 1915, Murray was leading 195 of her Salvation Army colleagues in erecting marquees, huts, and rest rooms that were used by over 110,000 soldiers every week. She was instrumental in laying the foundations of the Salvation Army’s extensive work for servicemen’s well-being throughout the Great War. Murray retired in 1919, and she was awarded the OBE in 1921.

Brigadier Murray worked in the Salvation Army’s women’s social work before she became secretary of their Naval and Military League. She served in the South African War in 1900, for which she was awarded the South African War Medal. On the outbreak of war in August 1914, Murray led a team to France to assist the British Expeditionary Force to assist in field hospitals. Murray was determined to be where the army needed help, regardless of the risks. She was at the battle of the Aisne in September 1914 where she was ‘slightly burnt’ by a shell. By 1915, Murray was leading 195 of her Salvation Army colleagues in erecting marquees, huts, and rest rooms that were used by over 110,000 soldiers every week. She was instrumental in laying the foundations of the Salvation Army’s extensive work for servicemen’s well-being throughout the Great War. Murray retired in 1919, and she was awarded the OBE in 1921.

Eleanor Barker, Britain, Director of St. Barnabas Society operations, Calais (by Mark Connelly, Professor of Modern British History)

In the spring of 1919 huge numbers of British people set out to see the graves of loved ones killed in the fighting of the First World War. Visiting the devastated zones of France and Belgium was a harrowing task for those suffering the agony of grief. For many thousands this challenge was made possible thanks to the tireless effort of Eleanor Barker. As the deputy director of the St. Barnabas Society, an organisation whose sole aim was to assist those visiting war graves, nothing was too much trouble. The indefatigable Barker organised travel, meals, hostels and accommodation, guides, and transport to and from the cemeteries. Her compassion, dedication and administrative skills ensured that the broken-hearted reached that sacred spot so important to them.

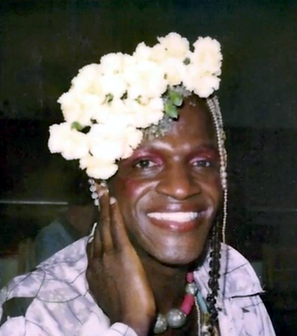

Marsha P. Johnson, 1945-1992 (by Kathryn Heffner, PhD student, winner of the Science Fiction Foundation’s 2022 Peter Nicholls Essay Prize)

Marsha P. Johnson was born Malcolm Michaels Jr. on 24 August 1945 in Elizabeth, New Jersey. Born into a working-class family, Johnson left home in 1963 to live and work in Greenwich Village. While in New York, Johnson became involved with the gay community and changed her name to “Marsha Pay-it-no-mind Johnson.” As a drag performer, sex worker and community activist, Johnson risked her wellbeing and safety as a black gender-non-conforming social justice advocate. During the 1969 Stone Wall riots in New York, it was claimed that Johnson had thrown the first shot glass a police officer which initiated the riot.

Throughout history, there has been a mythologizing of Marsha P. Johnson’s involvement with the Stone Wall Riots, Marsha herself claiming to not have been at the site until later. After the Stone Wall uprising, Johnson became involved in numerous gay and lesbian activist spaces. Johnson joined the Gay Liberation Front, a grassroots organization that quickly expanded to create global networks of queer and trans solidarity. Soon after joining the GLF, Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera founded the ‘Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries’ in 1970. This organization assisted homeless LGBTQ youth in New York, and set an example for other collectivized social service programs. ‘Queen Mothers’, Johnson and Rivera were sex workers in order to provide shelter, food, and care for homeless queer and trans youth.

Johnson continued advocating for the community and in 1987 was one of the founding members of the grassroots AIDS activist groups ACT UP. Marsha P. Johnson died on 6 July 1992, at the young age of 46. Johnson’s body was found in the Hudson River in New York, and was ruled by the police as a suicide. Johnson’s friends and community believe that Marsha was a victim of a hate-based crime; however policing agencies failed to conduct any criminal investigation on Johnson’s untimely death.