In today’s blog on Disability History Month, Dr Steven Taylor, Lecturer in History of Medicine, looks at the 2020 theme of ‘Access’ from a historical perspective and discusses some of his recent research.

Dr Steven Taylor

Over the course of this year a fierce debate has raged about the impact of Covid-19 on school-aged children and whether they should be mixing in schools. In the early-autumn when instances of virus spread seemed to decline the discussion became less heated, but the winter rise has again brought the issue into focus. Despite school closures, children considered by authorities to be ‘vulnerable’ or ‘at risk’ were encouraged to continue attending school, alongside those of key workers. The precarious social positions of ‘vulnerable’ children might lead one to argue that these youngsters have been treated differently from their peers as a direct consequence of their socio-economic status, rather than any deficit of ability.

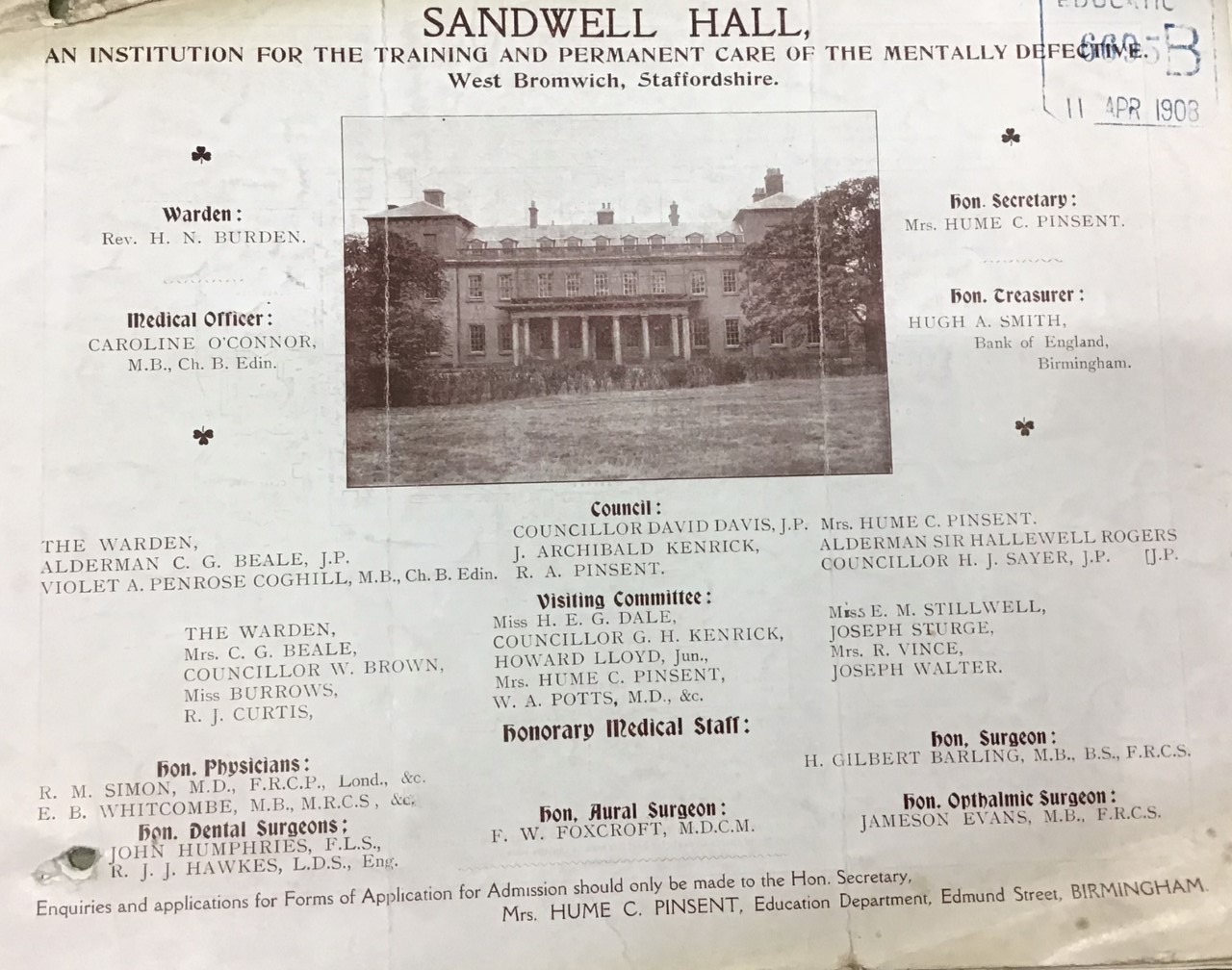

The themes of poverty and ability, or perceived lack of it, are central to my academic interests and this year has provided a chance to reflect on these topics as I work on my current research project. This research examines issues of access to education for the learning disabled, primarily through the prism of a residential school named The Sandwell Hall School for Mentally Defective Children. Quite obviously the name of the school is at best insensitive, at worst offensive, to our modern sensibilities, but it is important to handle names and labels in the historical context. Consequently, in the brief text that follows you might find certain words that are uncomfortable or insensitive, but these are used without judgement and only to gain a sense of past experience.

The Sandwell Hall School was one element of ‘special’ school provision that emerged in England and Wales at the beginning of the twentieth century. It was located on the outskirts of West Bromwich near to Britain’s second city of Birmingham. The idea for the school was put forward by the Reverend Harold Burden and Mrs Ellen Pinsent, who had both served on the Royal Commission on the Care and Control of the Feeble-Minded, 1904-1908. The report of the Royal Commission and the opening of the Sandwell Hall School, both in 1908, occurred as the reforming Liberal government were increasingly protecting the social status of children through legislation. This was a process that had been underway for 80 years: numerous Factory Acts, dating from 1833, had helped to reduce instances of child labour, and the Elementary Education Acts of 1870, 1876, 1880, and 1890 created a nationwide school system that was both compulsory and free. However, this educational network largely overlooked the needs of children who were described as ‘dull’ or ‘backward’. These children, who today would be described as learning disabled, were expected to attend school and take part in mainstream classes. The rote-style of learning made their attainment impossible and thus access to education only made disabilities more visible to peers, teachers, and the community more generally.

Without further investigation it might be considered that Burden and Pinsent were acting with a humanitarian ethos when they founded The Sandwell Hall School; they certainly would have claimed that they were doing the best thing for the children who attended their school. Historical investigation, however, reveals that Sandwell Hall was an experiment fuelled by degenerative, proto-eugenic discourse that believed industrial capitalism, increased social mobility, the growth of cities, and urban overcrowding were debasing human stock and placing strain on industrious members of society, through whom local rates levied for the welfare system. The children who attended this school were symbolic of this perceived genetic decline and their segregation and control was considered to be for the benefit of both the individual and society. The education they received was primarily manual and designed to reduce reliance on state welfare in adulthood.

Often we view the concept of ‘access’ through a lens of positivity. It can equate to new opportunities and acceptance. In this historical example, though, we clearly see that ‘access’ to education for the learning disabled was designed to ‘Other’ and segregate. As I draw to a close, the lesson to learn from Sandwell Hall is that it is easy to see positives through an uncritical lens. To gain real insights into experience we must ask questions about the nature of accessibility, whether it is granted or earned, the motives behind it, and, most importantly, who is the beneficiary.