For the latest instalment in our commemoration of Black History Month, our Head of School, Prof. Mark Connelly draws attention to an incident from the First World War which speaks of loyalty and sacrifice but also of segregation and ingratitude.

The First World War was truly that: a global experience. It was fought across the planet by people from every inhabited continent. For Africans, the war meant military engagement on their own continent, and people leaving it for service elsewhere. Among those who found themselves far from home were the men of the South African Native Labour Contingent. Reaching a total of 25,000, the SANLC was a vital component in the British Empire’s war machine on the Western Front in France and Belgium. By the winter of 1916 the logistics infrastructure supporting British forces was approaching crisis point. Stretched to its limits by the battle of the Somme, there was a pressing need to address a host of supply and labour tasks. Modern war demanded the loading and unloading of vast quantities of materials onto and from ships, once on the quayside those materials – ammunition, rations, fuel, military equipment and thousands of other items – needed shifting to railway trucks or motor lorries to reach their final destinations and uses; roads, canals and railways required maintenance or even construction from scratch, stone had to be quarried and trees felled. It made British forces on the Western Front a hive of activity, and by 1916 this meant vast numbers of men and women were engaged in supporting military operations.

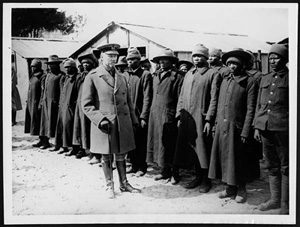

Looking to South Africa, the British government encouraged the recruitment of black men for service on the Western Front. The idea was supported by the South African Native National Congress leading to creation of the new units in September 1916. Men were soon enlisting inspired by a range of motivations. For some it was simply the chance to earn a regular wage while being clothed, fed and given the chance to travel. For others, it was an expression of loyalty to the British Empire signified by King George V. Black South Africans were going to show the Empire and the world that they were ready, willing, able and proud to do something to assist in the struggle. As one recruit told a journalist, ‘I answered the call of my King.’ The first battalions set sail that autumn reaching France in November. They were soon at work carrying out a range of tasks behind the lines, mostly lacking glamour and excitement, but vital for the overall war effort. Fearful that mixing with local people and other allied soldiers might encourage a greater sense of enquiry and independence, the South African government was keen to keep the contingents firmly segregated and largely confined to their own camps and barracks. Reflecting the degree to which the South African government wished to exert control and was suspicious of all outside influences, it even excluded British officers on the grounds that they were inexperienced at commanding African men. Nonetheless, the SANLC became stars of the Western Front. The War Office’s official newsreel filmed them at work in 1917, and another completed in 1918 captured the King’s visit to the SANLC, a demonstration of Zulu dancing and the wounded recovering in hospital. These films were then used to show British people how the entire Empire had rallied to the cause. At precisely the same time, such presentations also avoided any questioning of the concept of Empire and its actual power structures and hierarchies.

As the film showed, in making this contribution to Britain’s cause, the SANLC did suffer casualties. The single biggest cause of injury and loss of life came in February 1917 when the transport ship, Mendi, sank with the loss of over 600 members of the unit after an accidental collision with another vessel. As the ship sank, Isaac Wauchope Dyobha delivered words that have become famous in South African history telling his companions:

Be quiet and calm, my countrymen, for what is taking place now is exactly what you came to do. You are going to die, but that is what you came to do. Brothers, we are drilling the drill of death. I, a Xhosa, say you are all my brothers, Zulu, Swazis, Pondos, Basutos, we die like brothers. We are the sons of Africa. Raise your cries, brothers, for though they made us leave our weapons at our homes, our voices are left with our bodies.

In the immediate aftermath of the tragedy, there was the need to find and bury the bodies. As many as were found, many being washed ashore by the tides, they were buried and consequently marked with the official Imperial (subsequently Commonwealth) War Graves Commission headstones, while the missing were commemorated in Hollybrook Memorial in Southampton. Their comrades who fell while carrying out their duties in France and Belgium were buried in military cemeteries with a particularly large number interred at Arques-la-Bataille British Cemetery.

The fate of the Mendi caused much sorrowful mourning and was the source of much pride in South Africa. At times marginalised, the story of the Mendi was never quite lost or forgotten, and the anniversary was marked annually by both black and white communities. Such respectful remembrance was in some ways more than that given to the living. Keen to see the return of the SANLC, and thus firmly back under domestic control, the South African government wanted the men repatriated as quickly as possible, which resulted in the return of the vast majority before the end of the war. At that point the veterans were denied the British War Medal, despite its distribution to black Africans from the British Protectorates. Deliberately excluded from the honour of a medal, SANLC veterans were further angered at exclusion from the benefits and welfare schemes which war service should have brought. It led to a situation in which veterans often felt pride at their service and contribution to the British cause, but deeply disappointed that official recognition in the form of genuine change in South Africa was almost non-existent. However, the point had been made, and history could not be reversed. The men of the SANLC, their families, descendants and admirers provided an on-going testimony to their role in the Great War. With the birth of the new South Africa, their story became even more closely entwined with the Mendi incident culminating in the 2017 centenary when the event was marked by a series of commemorative ceremonies. The SANLC sailed the length of Atlantic to do the jobs that kept the forces of the British Empire going. They played their part in victory. Their experiences also reveal much about the complex way in which the Great War and European imperialism touched lives across the globe.

Useful materials:

Commonwealth War Graves Commission

CWGC Personal Story: Reverend Isaac Wauchope Dyobha

Albert Grundlingh, War and Society. Participation and Remembrance: South African Black and Coloured troops in the First World War, 1914-1918 (Stellenbosch: Sun Press, 2015).

B.P. Willan, ‘The South African Native Labour Contingent, 1916-1918,’ Journal of African History, Vol. 19, No. 1, 1978, pp. 61-86.

Timothy C. Winegard, Indigenous Peoples of the British Dominions and the First World War (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014).