Drawing on recent experiences with Wikipedia and Reddit, Dr Edward Roberts, Lecturer in Early Medieval History, considers the possibilities for public engagement and History in an age of pandemic.

Public engagement, according to the National Co-ordinating Centre for Public Engagement, ‘describes the myriad of ways in which the activity and benefits of higher education and research can be shared with the public. Engagement is by definition a two-way process, involving interaction and listening, with the goal of generating mutual benefit.’ In recent years, engagement has become a critical aspect of higher education in the UK: a responsibility performed partly in recognition of the public funding research regularly receives, but also something that nourishes the general public’s often underestimated interest in academic subjects. Engagement, additionally, seeks to raise awareness about the value and applicability of scientific and cultural knowledge in public life.

History is a subject for which public appetite has always been particularly strong: most people are interested in heritage on some level, in thinking about where we’ve come from and in understanding how we got to where we are today. Historians respond to these interests by showing how the past has been and continues to be used: how it informs modern identities, values and concepts, and how it provides critical perspectives on all sorts of contemporary issues. Engagement activities often involve experts communicating knowledge and research via media (print, radio, podcasts, TV), or through events, festivals or exhibitions, often organised in tandem with museums, archives and other heritage organisations. This kind of knowledge dissemination is important, though it is also often one-way communication, and it has sometimes proved difficult to move beyond this. Engagement, as mentioned, is a two-way process, and thus entails public participation and dialogue.

As many now recognise, the greatest opportunities for public engagement are increasingly to be found online. It would probably be fair to say that, as a discipline, History has been slow to confront the digital revolution. Wikipedia is perhaps the clearest case in point. Even though Wikipedia is easily the single-most consulted resource for historical knowledge in the world, many professional historians have been reluctant to engage with it. Its popularity is not hard to explain: unrivalled accessibility (completely free, and promoted by powerhouses like Google and Amazon) and completeness (over 6 million English-language articles and still growing quickly). For better or worse, it has become the place many now turn for history. For example, the article on the Frankish ruler Charlemagne (r. 768–814), a frequent subject of the modules I teach, received more than 5,000 daily views in 2019. As the archived pages of the article’s ‘talk’ page show, Wikipedians are constantly discussing its content and shape. Even articles on comparatively obscure subjects receive lots of views – take, for instance, that on the tenth-century historian Flodoard, which receives about 10 hits per day, more than 3,600 across 2019. I recently wrote a book about this man, and I’m pretty sure it’s going to take a long time for that to accrue as many readers as Flodoard’s Wikipedia article gets in a single year.

As many now recognise, the greatest opportunities for public engagement are increasingly to be found online. It would probably be fair to say that, as a discipline, History has been slow to confront the digital revolution. Wikipedia is perhaps the clearest case in point. Even though Wikipedia is easily the single-most consulted resource for historical knowledge in the world, many professional historians have been reluctant to engage with it. Its popularity is not hard to explain: unrivalled accessibility (completely free, and promoted by powerhouses like Google and Amazon) and completeness (over 6 million English-language articles and still growing quickly). For better or worse, it has become the place many now turn for history. For example, the article on the Frankish ruler Charlemagne (r. 768–814), a frequent subject of the modules I teach, received more than 5,000 daily views in 2019. As the archived pages of the article’s ‘talk’ page show, Wikipedians are constantly discussing its content and shape. Even articles on comparatively obscure subjects receive lots of views – take, for instance, that on the tenth-century historian Flodoard, which receives about 10 hits per day, more than 3,600 across 2019. I recently wrote a book about this man, and I’m pretty sure it’s going to take a long time for that to accrue as many readers as Flodoard’s Wikipedia article gets in a single year.

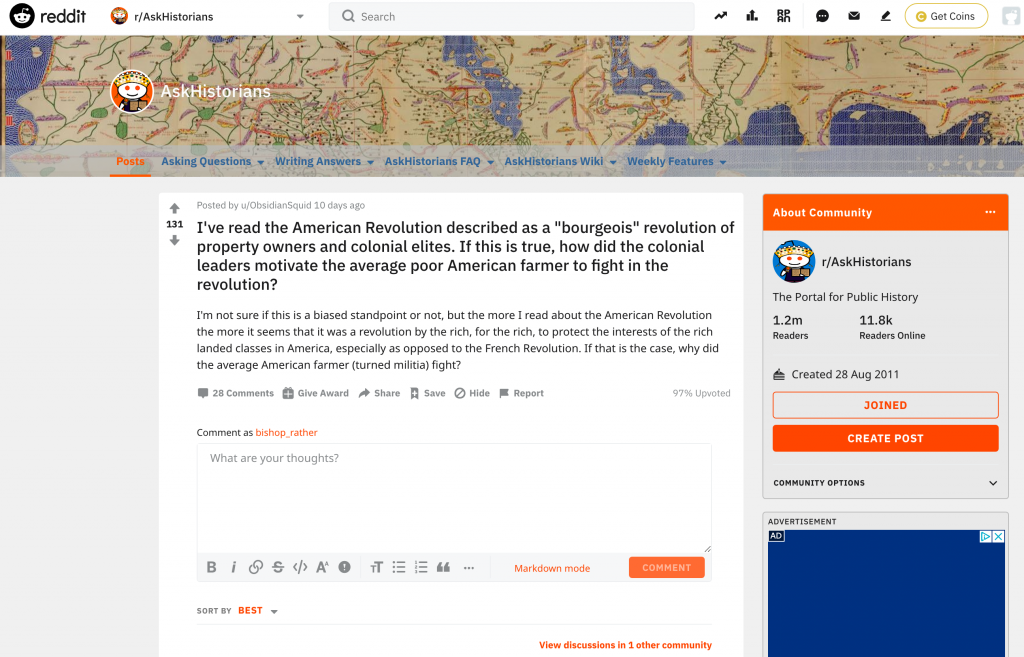

The interested public’s hunger to learn more about subjects many of us tend to think of as rather niche – like my own area of expertise, Europe in the ninth and tenth centuries – was further made clear to me when I was kindly invited by the Reddit community r/AskHistorians to participate in a Q&A (known on Reddit as an AMA, ‘Ask Me Anything’). r/AskHistorians is a public history forum with the simple premise that anyone can ask a question about the past and receive ‘serious, academic-level answers’ from its community of 1.2 million subscribers. That community includes experts and knowledgeable enthusiasts whose interests range across time and space, frequently resulting in far lengthier posts and discussions than a casual Reddit user might otherwise expect. The forum, or ‘subreddit’, is also much more heavily moderated than most others on Reddit, and there are strict guidelines about what kinds of questions can be asked (e.g. no ‘poll’-type questions, or counterfactual ‘what if’ questions) and how responses should be supported (e.g. appropriate use of primary sources, awareness of current historiographical debate).

So, I decided to take the plunge and devote an afternoon to an r/AskHistorians AMA. Even though I’ve been a casual reader and occasional commenter there for some time, I still approached hosting an AMA with some trepidation. What if I only got asked questions I didn’t know much of anything about? Would anybody even turn up to ask a question? You can see how the whole thing went here. Happily, my fears were unfounded. Within minutes of posting my thread, questions started flowing in – much more quickly than I could keep on top of. By the end, more than 100 questions had been asked, and I was only able to respond to about 30. I’ve been going back periodically to answer a few more when I can, because there were so many good questions asked that I didn’t get around to. Probably some of my responses were a bit too long, but this community appreciates detail, so I hope I can be forgiven.

So, I decided to take the plunge and devote an afternoon to an r/AskHistorians AMA. Even though I’ve been a casual reader and occasional commenter there for some time, I still approached hosting an AMA with some trepidation. What if I only got asked questions I didn’t know much of anything about? Would anybody even turn up to ask a question? You can see how the whole thing went here. Happily, my fears were unfounded. Within minutes of posting my thread, questions started flowing in – much more quickly than I could keep on top of. By the end, more than 100 questions had been asked, and I was only able to respond to about 30. I’ve been going back periodically to answer a few more when I can, because there were so many good questions asked that I didn’t get around to. Probably some of my responses were a bit too long, but this community appreciates detail, so I hope I can be forgiven.

I was struck by the range and quality of the questions that came in. Many asked incisive questions about key aspects of my aforementioned recent book, which deals with the writing and representation of history in the tenth century. There were also a lot of highly specialised questions from individuals who clearly had superb knowledge of the medieval world. Others had more general questions about the period I work on – when did Gaul become ‘Francia’, and when did Francia become ‘France’? What kind of contact was there between Britain and the continent in the early Middle Ages? How important was the slave trade in the economy of the Carolingian Empire?

The entire experience was deeply gratifying (if somewhat exhausting!). I was delighted and surprised to receive questions from so many people interested to learn more about what I’ve long considered to be my fairly obscure corner of medieval history. And from the perspective of public engagement, conducting an AMA opened my eyes to the vast potential communities like r/AskHistorians have to offer university-based academics. The thread attracted more than 2,700 upvotes (the way Reddit displays its content is determined by its own communities, so users can click to ‘upvote’ items of value or ‘downvote’ things they don’t like). The r/AskHistorians mod team sent me some additional metrics, showing that the thread was viewed over 18,000 times, a figure that astounded me. The audiences for history of all sorts are out there, and they are eager to speak with specialists.

What’s more, I felt that my interactions with questioners genuinely benefited my own historical thinking. The AMA format forced me to think quickly and to boil down often complex topics into relatively concise explanations and interpretations. Some questions dealt with topics and issues familiar to me in different or unusual terms, encouraging me to see things from fresh perspectives. That’s precisely the kind of two-way benefit envisaged in public engagement.

As we continue to grapple with Covid-19, we are quickly becoming much more comfortable operating virtually. A great number of summer conferences and seminars (including our own MEMS Fest) successfully made the jump to virtual format. Many historians are well aware of the vast potential offered by this shift. The Institute of Historical Research, for instance, is seeking to shed its reputation as a London institution by expanding its seminar programme on a national level. And even before the onset of the pandemic, my colleagues here in the School of History developed and launched a free Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) on the history of the British army, which in its current iteration has more than 4,000 subscribers. As platforms offering the possibility of mass participation on a global scale, such venues as those discussed here are going to become ever more important for engaging an avid public with the past.

You can follow Ed on Twitter here: @e_c_roberts.