In response to recent debates over the way Britain’s imperial past should be commemorated, Archbishop Justin Welby has stated that certain monuments in Canterbury Cathedral would need to be looked at “very carefully”. As the School of History’s Dr Ben Marsh discusses below, the Church of England, like most powerful British institutions, was deeply implicated in the slave trade, but any changes to commemorative spaces need to recognise the complexity of this involvement.

The remarks by the Archbishop of Canterbury last week over the need to scrutinise the Church of England’s monumental landscapes have prompted a backlash of concerns. Ironically, instigating a quest to identify contentious figures celebrated on statues and plaques at iconic sites such as Westminster Abbey and Canterbury Cathedral has added to Justin Welby’s own profile as a contentious leader. Because of the recent campaigns to rebalance the heritage that is displayed in civic spaces, and to take account of historic racial injustices and their ongoing legacies, the subject is a hot one. Much hotter than the oft-eroding stone and metal façades themselves, many of them tucked away in crevices, shadows, or hidden under ivy and moss. A further irony, of course, is that the Church of England’s original break from the Papacy was accompanied by a spate of cultural iconoclasm in the sixteenth century on a quite unprecedented, breath-taking, national scale. Statue destruction, we might say, was an instrumental part of the foundation of the Church of England.

Given the Church’s institutional and political dominance throughout most of British history, it should come as no surprise that the Anglican faith – like almost all others – was deeply implicated in Europe’s imperial expansionism and its colonial brutalities. From the sixteenth century, these were disproportionately perpetrated against the indigenous peoples of Africa and the Americas, who were victimised at a structural, legal, physical, and economic level that exceeded maltreatment of other Europeans. But the Church of England and its leadership arguably bore a heavier historical footprint than others in these developments for two reasons: firstly because they officially sanctioned key measures such as the affirmation that being Christian did not preclude being enslaved (in seventeenth-century British colonies), and secondly because they administered vast quantities of acreage – including not just estates in the British Isles but in Britain’s overseas colonies (largely an eighteenth-century development). In cultural and in economic terms then, the Church was up to its eyes in the racial abominations through which the nation developed and the empire expanded – and many Anglican influences would remain obstinately pro-slavery in the early nineteenth century, even while most gradually embraced abolitionism.

Assessing the eyes looking down on aisles and pews is complex – more complex, even, than the arguments around Colston, Rhodes, and Confederate generals who actively pursued racial injustices in their chosen vocations. For one thing, links between the historic exploitation of – say – black lives and the Church were often indirect and subtle. The sort of success that brought visible memorialisation to the white male figures dotted around parish churches or in grander cathedrals derived from military campaigns, commercial winnings, inherited wealth, or manufacturing entrepreneurship. These were intimately but sometimes imperceptibly tied up with the exploitation of global empire: its lands, commodities, corporations, peoples. Even more problematic is the fact that Anglican Churches – more so than many metropolitan parks or plazas – have an active duty today to service their communities of faith, whose sense of their heritage and spirituality is bound up in monumental aesthetics and acoustics. The challenge is therefore a profound and sensitive one, because the scrutiny is destabilising for two different communities, both of which are under perceptible existential threat: as racial injustices persist, so do Anglican congregations decline.

To be successful, a decolonising commission will need to confront and navigate these many overlaps in the shared origins and trajectories of Anglican mission and Anglo colonialism. Choosing where it should end is arguably more important than choosing where it starts. But as far as Canterbury Cathedral is concerned, some obvious attention might gravitate to a handful of figures and episodes. For example, among the 55 statuettes populating alcoves in the west façade and the south west porch – almost all designed and erected in the 1860s – are berths for Richard Hooker (1554-1600), Dean Isaac Bargrave (1586-1643), and Dean George Stanhope (1660-1728). Hooker had acted as the mentor for the Anglican clergy of the first English slaveholding colonies, and his theological ideas and works (such as Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity) were an inherent part of the education and sensibilities of the first generations of planters (including the many lay vestrymen in colonies such as Virginia, where Anglican ministers were paid in tobacco harvested by indentured servants and, increasingly, enslaved Africans). He and others helped Anglo-Virginians to think their way to justifying racialised labour patterns – so that the Hebraic slave code described in Leviticus or the Curse of Ham described in Genesis were repurposed to support enslaving Africans in hereditary perpetuity.

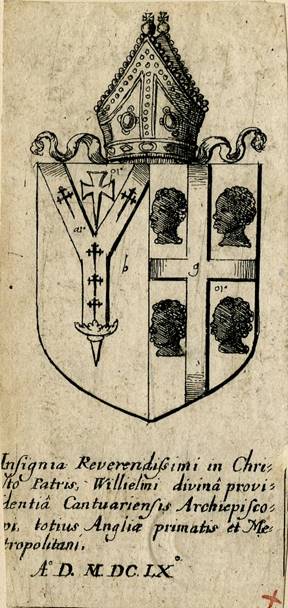

Isaac Bargrave hailed from a family in Bridge who bolstered their socio-economic profile thanks to overseas trade and settlement in the early seventeenth century. His brothers developed plantations and traded in the products of enslaved labour – one of them, George, bringing the first documented African and indigenous coerced labourers to an ‘English’ colony when they deposited people from the Caribbean to the infant Bermuda colony in 1616. The Bargraves’ Atlantic trading helped them to cement the dynasty’s domineering position around Canterbury. Isaac’s nephew, John, was appointed a canon of Canterbury Cathedral in 1662 and himself embarked on a mission to Algiers to ransom English captives held in North African slavery, later requesting that chains be placed above his tomb to commemorate his Christian-saving antislavery achievement. By then, the Archbishop of Canterbury was William Juxon, who himself had forged connections to the early English slave trade through commercial dealings. Juxon sported ‘four black Moors’ heads’ on his coat-of-arms which were granted in 1630, and he used busts of these to stylise the Great Hall at Lambeth Palace.

Dean George Stanhope, like many others, tended to view Native Americans and black populations as ‘heathens’ and was a spearhead of the official Society of the Propagation of the Gospel (SPG, established in 1701) which pursued Church of England missionary activity while accepting slavery as fundamentally sanctioned by both natural law and the Bible. Slavery and Anglicanism grew in concert in places such as Barbados, Virginia, and South Carolina. Most significantly, Anglican societies such as the SPG came to possess sugar estates (particularly the Codrington plantations in Barbados) which embroiled the Church of England’s hierarchy directly in the business of slavery from the early eighteenth century. Indeed, the SPG would go on to own more enslaved people than it employed as missionaries, and each new Archbishop of Canterbury was its president, helping to embed the global transference of ideas about slavery, race, and human difference. One eighteenth-century Archbishop, John Potter, chaired a meeting of the SPG in 1744 which approved the Society purchasing ‘20 New Negroes [Africans]’ while another future Archbishop, Frederick Cornwallis, was hostile to abolitionist sentiment, beginning a sermon emphasising the need ‘to pay Obedience to the Powers that were established in the World’ and render unto Caesar. When enslaved people were finally emancipated throughout the British Empire in 1833, the Church of England would be institutionally compensated to the tune of £8,823 for freeing its enslaved labourers on Codrington – quite apart from the extensive sums paid by the government to clergymen as individuals. The profits of slavery were elsewhere physically documented within the Cathedral grounds, though their traces have disappeared from public view: at the repaving of the nave in the 1990s, the arms and gravestone of Nathaniel Herring (d.1716) were removed, who at his is death owned 201 enslaved people on Jamaican estates, worth £5,739*.

These are the sorts of connections and toxic heritage that a fuller historical and monumental investigation will flush out in much greater depth. Something that is so long overdue ought to be progressed urgently but also with great deliberation and as much consensus as possible. The spaces are in need of corrective re-curation, but not damage or defacing. That the Church of England played a prominent part in vandalising the life prospects of other peoples in history, and served to bolster slavery’s moral acceptability and profit from it in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, is incontrovertible. But it did not do so in a vacuum, and just as the history must always be re-examined, so there ought to be space made for education and three-dimensional restitution.

Follow Ben Marsh on Twitter: @MarshBen1.

*Editor’s note: 06/07/2020 – The article has been updated at the request of the author to reflect that the arms and gravestone of Nathaniel Herring are no longer on display within the Cathedral as was previously stated.