In the closing months of 1929 the women of Nigeria rose up against British colonialism in a coordinated effort that has subsequently become known as the ‘Women’s War’. Rioting against the power of British-imposed Warrant Chiefs, women from the Igbo ethnic community congregated in their thousands, re-mobilising the traditional practice of ‘sitting on a man’ as a form of anti-colonial and anti-corruption collective action. Ostensibly a revolt against the imposition of a tax specific to Nigerian women, whose marketplace activities allowed them a level of financial independence from their husbands at the same time as supporting their families, the causes of the revolt can be traced back to the imposition of Indirect Rule in Nigeria under Lord Lugard in 1914. The Women’s War was a co-ordinated strategic rejection of British colonialism, and led to reforms in the way the colony was ruled, as well as the abolition of the women’s tax itself.

In the closing months of 1929 the women of Nigeria rose up against British colonialism in a coordinated effort that has subsequently become known as the ‘Women’s War’. Rioting against the power of British-imposed Warrant Chiefs, women from the Igbo ethnic community congregated in their thousands, re-mobilising the traditional practice of ‘sitting on a man’ as a form of anti-colonial and anti-corruption collective action. Ostensibly a revolt against the imposition of a tax specific to Nigerian women, whose marketplace activities allowed them a level of financial independence from their husbands at the same time as supporting their families, the causes of the revolt can be traced back to the imposition of Indirect Rule in Nigeria under Lord Lugard in 1914. The Women’s War was a co-ordinated strategic rejection of British colonialism, and led to reforms in the way the colony was ruled, as well as the abolition of the women’s tax itself.

Indirect Rule and British Colonialism

Lord Frederick Lugard was famously the architect of indirect rule in Nigeria, a policy by which the British handpicked local African elites who were friendly to colonial rule as ‘Warrant Chiefs’, responsible for the day-to-day running of the colony, and in particular the administering of the law, the organisation of labour, and the levying of taxes. The appointment of the Warrant Chiefs was not only an attempt to have ‘colonialism on the cheap’ on the part of the British, but also to impose British notions of colonial hierarchy – including changes to the gender relations of the people. While in Igbo culture, women and men worked collectively, the British imposed systems of forced labour and taxation that pushed women into what they considered their rightful place: the domestic sphere. When they attempted to tax women’s economic activities (the selling of palm-oil) in 1929, rioting and protest ensued.

‘Sitting on a man’

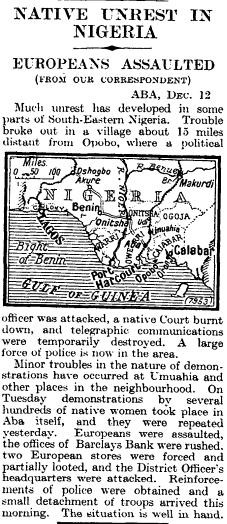

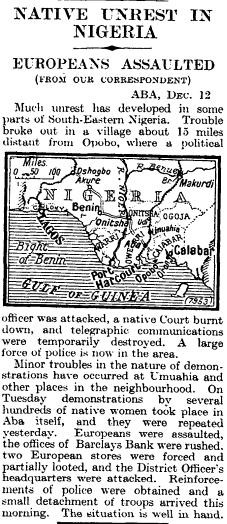

The women of the ‘Aba Women’s Riots’ (as they were known by the British) cleverly fused traditional forms of protest with collective action against the colonial state. They embarrassed the local Warrant Chiefs by ‘sitting on’ them – a ritual action involving dance, lewd gestures, songs and noise. At the same time, though, they attacked Native Court buildings, cut down telegraph wires, and damaged banks, post offices and factories – all seen as manifestations of white colonial oppression. Thousands of women were involved, and many more suffered from the reaction of the British, who burnt down villages as collective punishment, and fired into crowds of protesting women. In one incident at Opobo on 16th December eighteen women died at the hands of colonial troops, leading to questions in Parliament back in Britain.

Collective Action

Female protesters involved in the Women’s War were savvy and determined. They wore palm leaves as a link to the economic roots of their discontent, they mobilised traditional practices of protest through marching, singing and dance, and they disrupted the administrative mechanisms of the colonial state. Despite attempts in the British press to put this down to female ‘hysteria’, the Women’s War is an example of collective and organised female political and economic action. The British introduced reforms to the Warrant Chief system in an attempt to curb corruption, and abolished the women’s tax itself. Women also became involved in administration, but continued their action when necessary in future disputes such as the Tax Protests of 1938 and the Oil Mill Protests of the 1940s.

Women and Political Activism

‘A feature of the disturbances was that women were the actual aggressors’, noted a shocked correspondent for The Times in January 1930. ‘The trouble was of a nature and extent unprecedented in Nigeria’, continued the correspondent for Nigeria in August of that year. ‘In a country were the women throughout the centuries have remained in subjection to the men, this was essentially a women’s movement, organised, developed, and carried out by the women of the country, without either the help or permission of their menfolk, though probably with their tacit sympathy.’ The Commission sent to investigate the revolt, and the reactions of British troops in particular, came to many conclusions. Perhaps the most interesting for us in the current context is this: ‘More attention… should be paid to the political influence of women.’

Dr. Emily Manktelow