On 21st October Dr Will Norman gave a research seminar on the ‘strange career of Saul Steinberg, an emigre artist best known for his New Yorker covers in the US postwar era’. To give those who missed the event, as well as those who would like to revisit this fascinating subject, a taste of what was discussed (including the views and opinions of the elected respondents, the art historian Professor Martin Hammer and Lecturer in Creative Writing, Amy Sackville) here is an overview of what was said.

Will Norman expands on his paper on Steinberg:

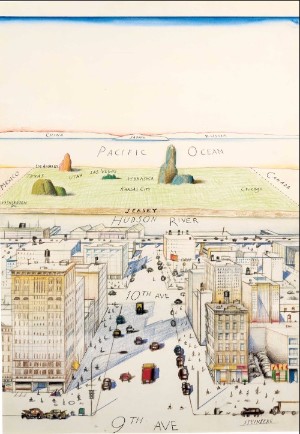

Last week I was invited to speak in the School of English research seminar about my recent research on the artist Saul Steinberg. Steinberg was a Romanian Jew who left Europe for the United States, arriving in 1942. During World War Two he served the United States with the OSS, a forerunner of the CIA, working on propaganda and counter-intelligence across the world. In the postwar years he became known for his covers and humorous drawings for the New Yorker magazine, and his most iconic cover, A View of the World from Ninth Avenue (1976) became one of the most reproduced images of twentieth-century American art. In 2014 I was able to research the Steinberg archive in the Beinecke rare Books and Manuscripts Library at Yale University, as part of a Fulbright Scholars Award. My talk drew on that research in taking up the question that Steinberg grappled with throughout his career: how to represent a state on a piece of paper?

The talk focused on two moments in Steinberg’s career: firstly the drawings of US servicemen that he made during his service in World War Two, and secondly his giant mural for the American pavilion in the Brussels World’s Fair in 1958. As an exile and a Levantine Jew, Steinberg was deeply ambivalent about the idea of the state as an appropriate way to organize culture, but he nevertheless took up positions of knowing complicity with the United States in ways that impacted his developing aesthetics. I explored how his position of complicity with the state was expressed through motifs of duplicity, camouflage and surveillance.

It was a pleasure to share my recent work with colleagues and students across the faculty, and especially to receive astute responses from the art historian Professor Martin Hammer and the novelist Amy Sackville. A lively conversation followed the talk, in which questions about aesthetic form, US imperialism and the construction of Jewish identity was pursued. My forthcoming book, Transatlantic Aliens: Modernism, Exile and Culture in Midcentury America, addresses Steinberg and other exilic figures in relation to such issues, and will be published in 2016.

Amy Sackville’s Response:

Will Norman’s paper offered a fascinating insight into an artist ‘hiding in plain sight’, maintaining a position as an ‘invisible’ observer both inside and outside of the culture(s) he inhabited. Picking up on Will’s discussion of an extraordinary image of Steinberg’s, in which he imagines himself living within the ‘dragon’ of culture, making a cosy home for himself among its organs, we discussed the ambivalence of his self-perception as artist, illustrator, and satirist. As I’m working on a novel which places an artist-as-observer at its centre (a centre which is necessarily unstable and shifting), reading and responding to the paper was an incredibly useful exercise for me, as well as being a valuable opportunity to learn about a colleague’s research, and to think about how creative, art historical, and critical perspectives might speak to each other.

Martin Hammer’s Response:

Everyone pays lip service to interdisciplinarity but most of the time we operate within our subject conventions and communities. I admire Will Norman’s willingness to align visual artists with writers in his argument about how European exiles responded to America during the Cold War period, and also to bring an art historian into the debate. I tried to inject a note of caution about reframing Steinberg from contemporary scholarly perspectives, which probably reflected my own preconceptions about his work, but I think this made for a productive discussion. The idea of giving a couple of respondents prior access to the paper is an excellent one, which we should adopt in Arts, and I was delighted to be involved and to get better acquainted with colleagues in another school.