At our most recent research forum we were joined by Dr Michael Falk and Bonisha Bhattacharyya for a fascinating discussion of the state of digital humanities research in India and Australia.

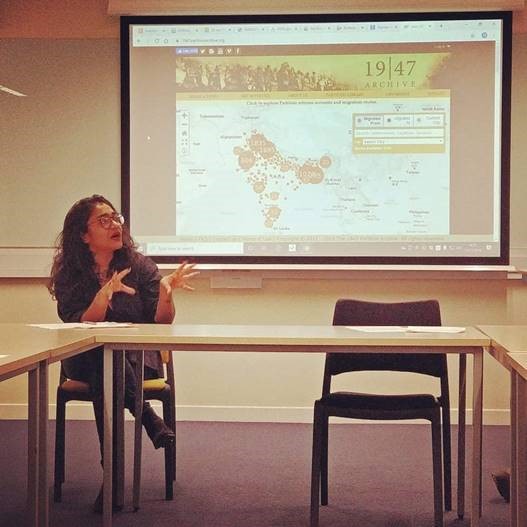

Bonisha Bhattacharyya’s talk discussed the present Digital humanities space in India. She brought in her colleague Dibyadyuti Roy from IIM Indore, to talk about The Digital Humanities Alliance for Research and Teaching Innovations or DHARTI. She discussed how Digital Humanities in India at the moment operates mostly out of the academic sphere, and that the present challenges involve a Rethinking of the role of technology in the classroom, in curricula and resources, and working towards a digital pedagogy.

In the case of archival work, which is another significant interest to DH work in India, Bonisha mentioned that there are specific challenges in terms of storage and preservation of materials, cross-referencing and meta-data standards, conditions and structures of access, roles and forms of curation, re-usage of archival materials in research and pedagogy, and, the constraints to digitisation of archival materials, particularly in terms of rare materials and those in Indian languages.

Michael Falk discussed some of the contradictions of Digital Humanities in Australia, where the colonial context continues to shape the debate. On the one hand, Australia has some of the most successful and open Digital Humanities infrastructure in the world. The Trove database gives scholars the ability to interrogate a vast number of Australia’s physical and digital collections across the country, contains thousands of images and government documents, and contains more than 300,000,000 digitised newspaper articles. Its public API allows digital humanists to harvest materials en masse. And its virtually unique crowdsourcing campaign has seen thousands of members of the public collaborate with the National Library to hand-correct the text of digitised newspaper articles. Trove is a shining example of the open access ethos that drives the most successful DH projects.

While this open-access and community-driven ethos has won plaudits around the world, there is trouble brewing. Trove itself has never come under attack—the service is too valuable and too popular for that. But the ideal of open access more generally is starting to rub up against the complex problem of Indigenous Data Sovereignty. Indigenous scholars and activists are increasingly demanding control of research data that describes them. Scholars and the public are increasingly aware that humanities data is not simple or atomistic. What data is collected, who collected it, and how it is disseminated, all have a profound impact on the meaning of the data in practice.