We’ve been working very hard behind the scenes here recently on an exciting part of our project – the temporary exhibition at the Petrie Museum, showcasing our research on the musical instruments in their collection and our work creating playable replicas.

We are excited to announce that our exhibition opens to the public on the 22nd January 2019!

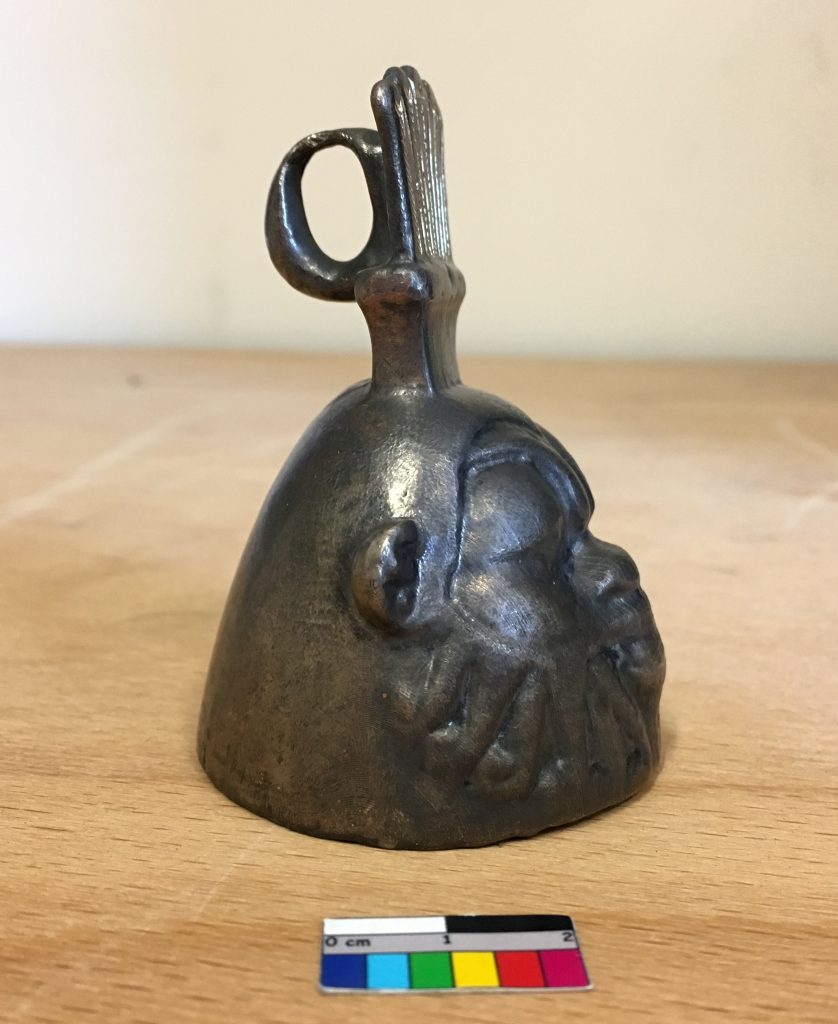

The exhibition reveals how different instruments were used to create particular experiences, for instance the role of instruments within religious and ritual activities, in the Egyptian home, and in processions and performances. Sound-making objects were important not only for entertainment, but also had practical uses in everyday life, for instance as toys, protective amulets, and alert or alarm sounds.

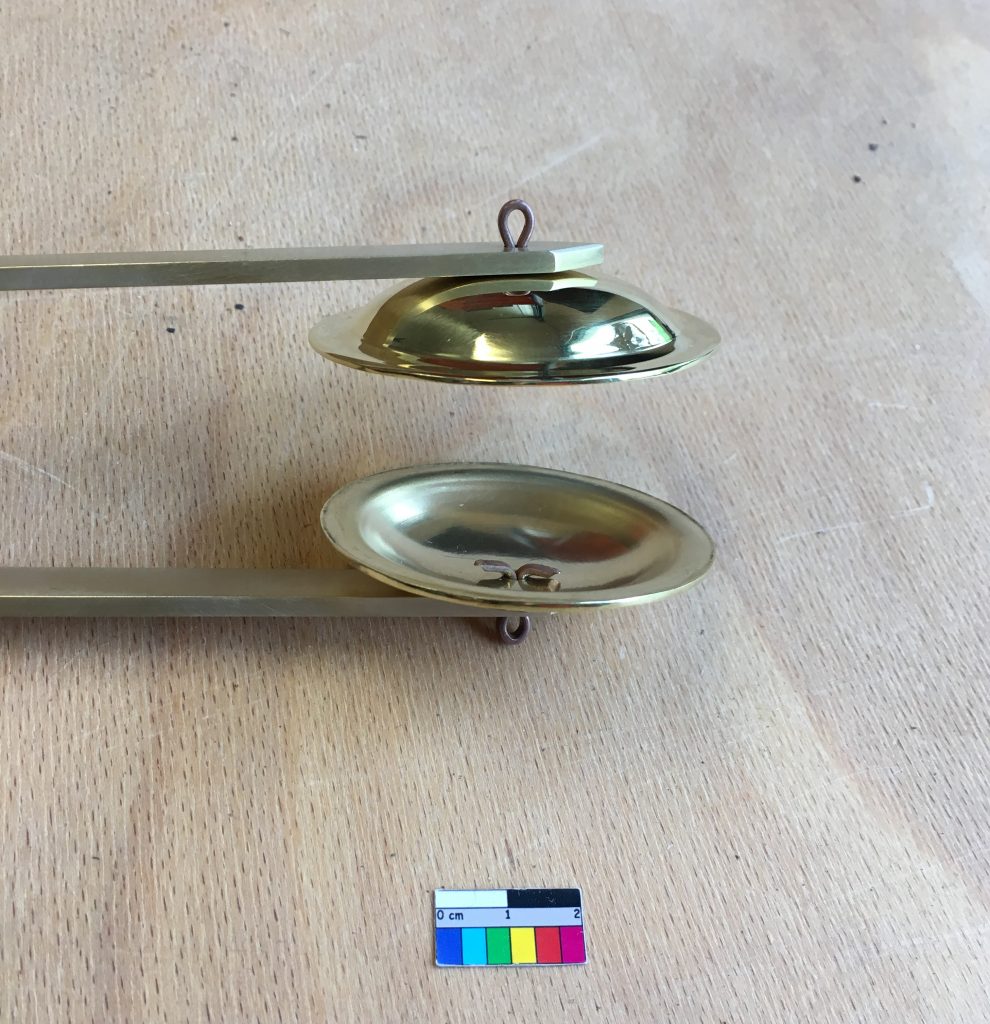

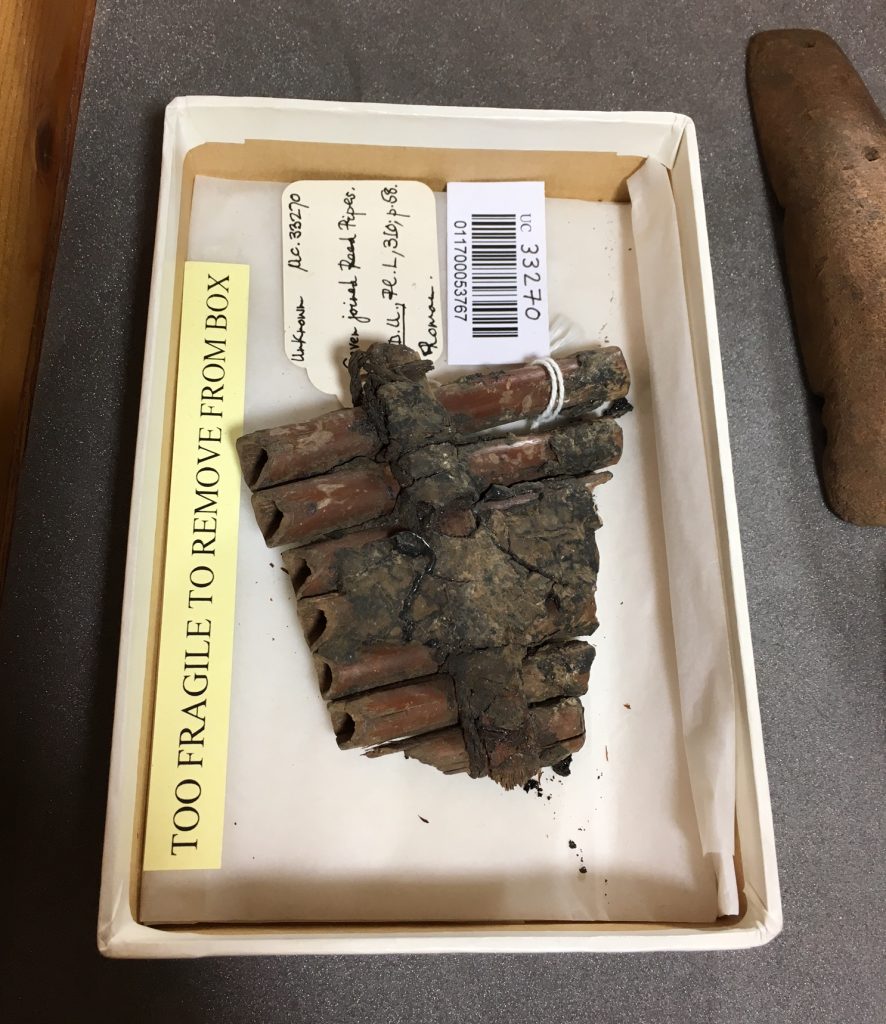

The replicas (discussed in blog posts here and and here, and based upon the sound-making artefacts within the Petrie’s collection) form an integral part of the exhibition. We have used this display as an opportunity to show the processes and technologies involved in their creation – from laser-scanning and creation of 3D virtual models by Kent Archaeology technician Lloyd Bosworth, to 3D printing. The craft replicas produced by University of Kent technicians Georgia Wright and George Morris, and local jeweller Justin Richardson in materials like ceramic, wood, and bronze are also included.

Visitors will see the original Roman instruments displayed alongside some of the modern replicas, and learn about how they were used in the Roman period. Some replicas are also available to be handled and played, with additional sound recordings providing an evocative illustration of the sounds of Roman Egyptian life.

These sound recordings were created using computer software that mimics the acoustic qualities of specific interior and exterior spaces. Information on Roman buildings from archaeological excavations in Egypt has been used to allow us to hear the sounds of the instruments as though they were being played within these ancient spaces. Further evidence from ancient sources, such as musical texts from papyri documents, has allowed authentic tunes, rhythms and scales to be replicated. See below for a preview of one of the replica sets of cymbals (based on UC35798) played with one hand in the Paeonic 5/8 rhythm!

A lot of work has gone into the production of this exhibition from writing text for information panels (and making sure it is the correct length to fit the space!), to selecting which artefacts would be best to display (taking into account factors such as their state of preservation), to programming the computers with sound clips via a user-friendly interface. We also sourced an Arabic translator to ensure that non-English speaking visitors could benefit from the display. We are thus incredibly excited to share this event with you!

Finally there will be a series of public workshops based around our replica instruments aimed at both families and the general public to accompany the exhibition – please see here for further details. These workshops provide an opportunity to try out the full range of replica objects, hear live demonstrations, and learn how to play some ancient rhythms. A Key Stage 2 schools-pack with additional materials will also be available to download from the Petrie Museum website.

The exhibition is located in the pottery gallery of the Petrie Museum – further information including opening hours and the museum’s location can be found here.