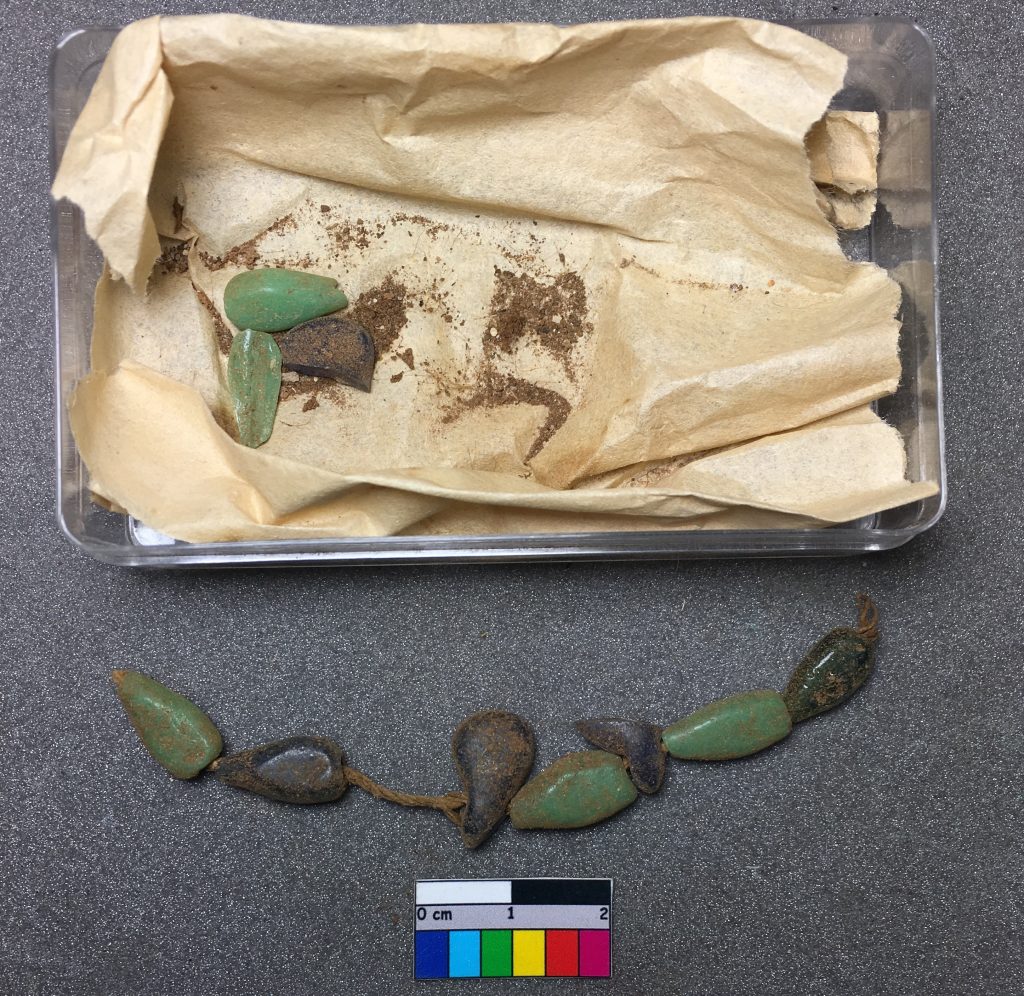

As we have seen in previous posts, organic materials like textiles and wood survive much better archaeologically in the hot and sandy Egyptian environment, compared to elsewhere in the Roman Empire. In fact, a brief look through the online catalogue for the museum shows that many of the beads from the Roman period still feature the original thread on which they were strung! Thus we have sections of beads that appear in their original order when originally worn as necklaces and other jewellery pieces.

What is also apparent is that coloured string or cord was commonly used as decorative bands on which beads and other pendants were suspended, to form necklaces and bracelets. The decorative nature of such threads can be seen in UC27846i (below). In this example from Roman period Lahun, black fibres have been knotted with those coloured a yellowish ochre to form a striking pattern which complements the striped shells used as beads.

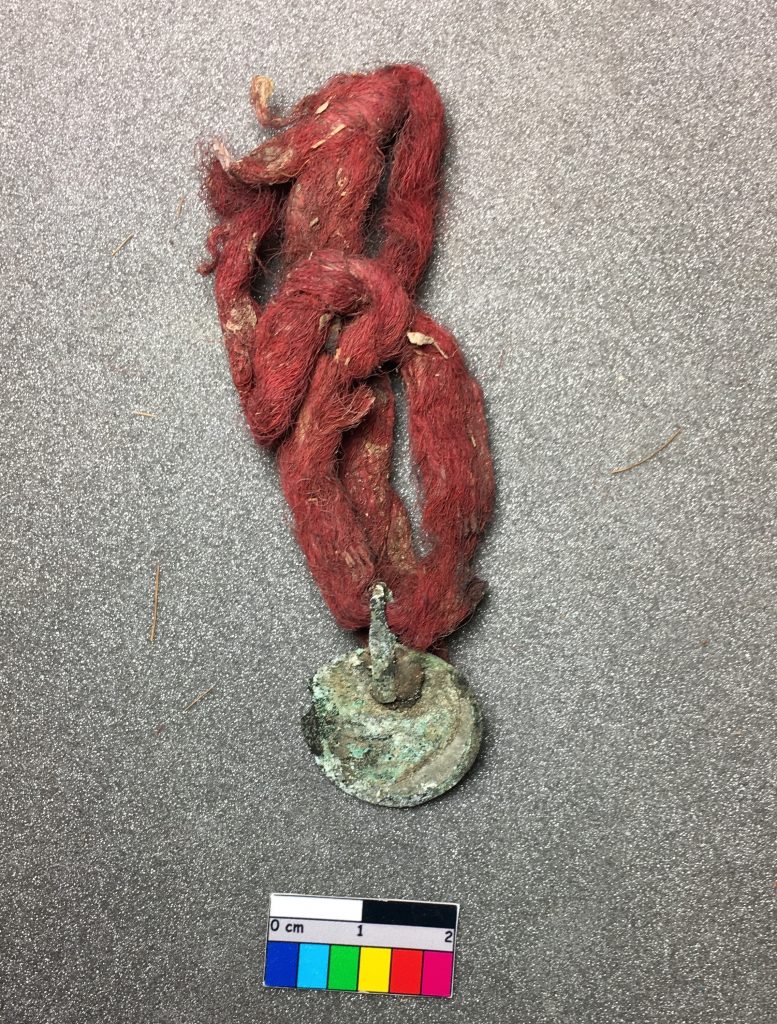

Another significant use of colour is the presence of red string in bracelets and necklaces. UC64872 is a thick piece of very loosely spun wool, dyed a vibrant shade of red and strung with a cu alloy disc shaped pendant. The wool has been knotted to form a large loop, big enough for a child or small adult’s necklace.

The vivid colour is striking; red dyes in Roman Egypt included the mineral ochre, as well as plant dyes from madder (rubia tinctorum), safflower (carthamus tinctorious), henna (Lawsonia inermis), and alkanet (Alkanna tinctoria). An insect-based dye, similar to modern cochineal and using beetles of the kermes genus, was also used to produce a vivid crimson red. By looking at the numbers of red stringed artefacts in the Petrie’s Roman collection, it becomes clear that there is a meaningful preference for this colour. Out of 101 artefacts featuring string, red was the second most popular colour after natural or undyed string. There is also a clear correlation between the use of red dyed string, and artefacts relating to personal adornment. Such colour choices can begin to be explained by evidence from the textual record.

Red materials, both man-made and natural (like dung) appear in spells from the Greek Magical Papyri; descriptions from Pliny the Elder also describes the use of red cloth and flies in magical spells (Natural History, 30.27; 30.30). The late antique Gaulish writer Marcellus Empiricus’ prescribed red wool stuffed into the ear for earache (De Medicamentiis 9.14.37). Other Roman writers reveal that red threads had a specific protective or ‘apotropaic’ role in the early Christian period. A 2nd c. AD description by Clement of Alexandria decried those who worshipped, “dread tufts of tawny wool” (Stromata 7.4), whilst the fourth-century Bishop of Constantinople, John Chrysostom, provides a description of artefacts similar to those in the Petrie Museum:

“[…] what shall we say about the amulets and the bells which are hung upon the hand, and the scarlet woof [spun wool], and the other things full of extreme folly; when they ought to invest the child with nothing else save the protection of the Cross […] while the thread, and the woof, and the other amulets of that kind are entrusted with the child’s safety […]”

(Homily 12 on 1 Corinthians 4.6: PG 61.05)

Therefore it appears that in the early Christian period, red wool was used as an amulet to protect the wearer, especially in the cases of children who were naturally more at risk to death and disease. They were often worn around the wrist, a size which correlates to the examples in the collection.

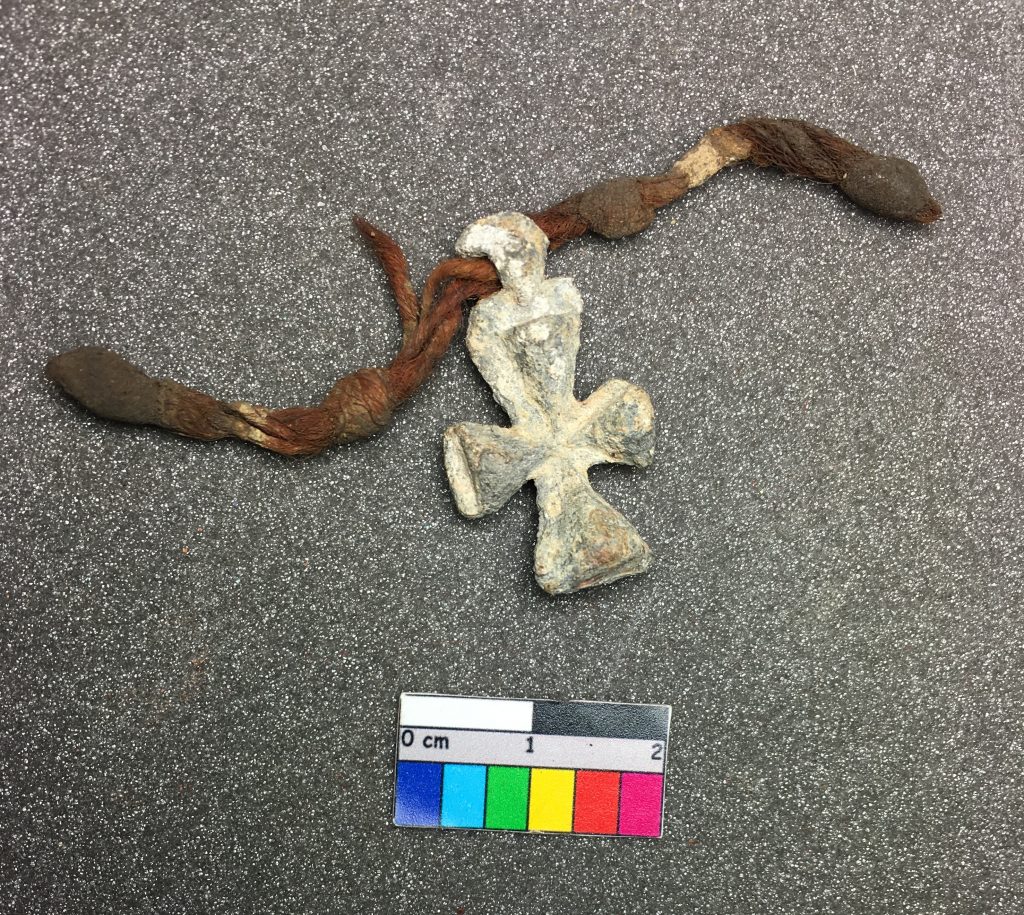

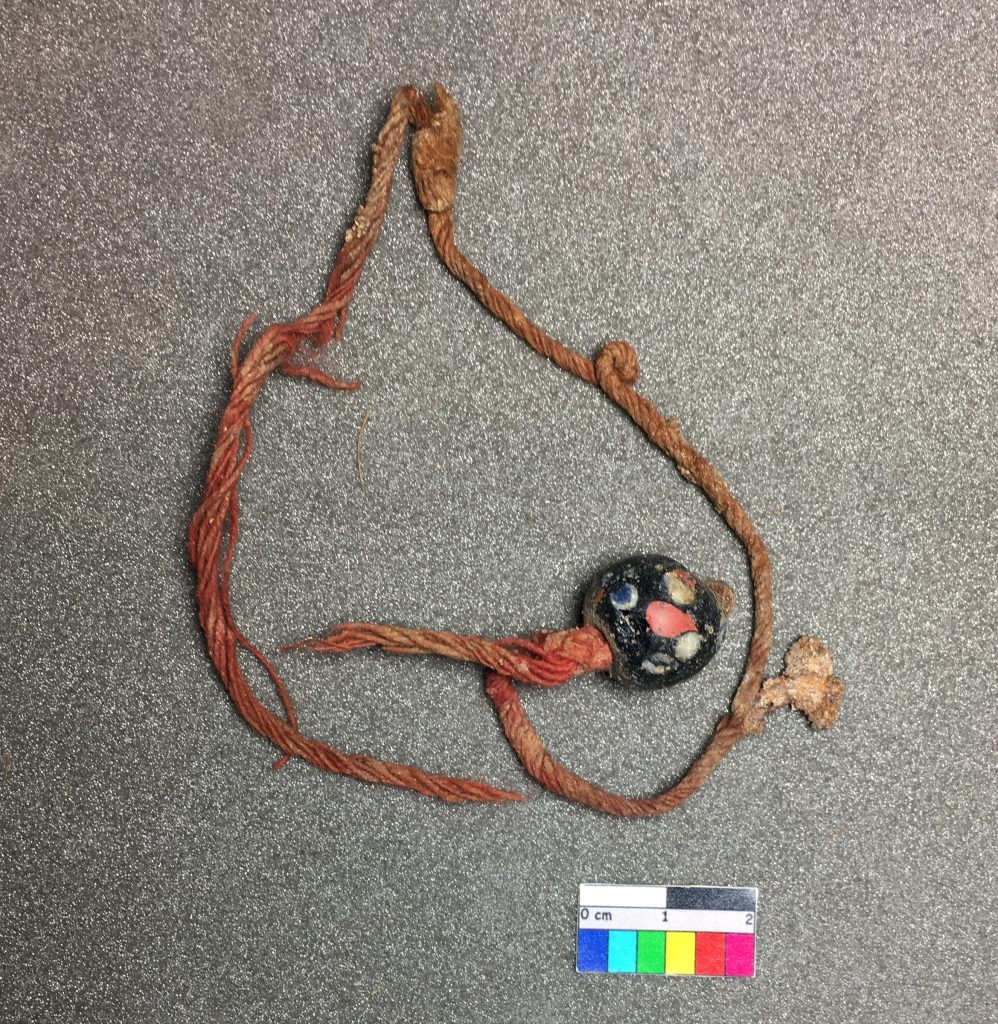

This use is also reinforced by the presence of amuletic pendants in the form of protective symbols – the use of the cross as such is described by John Chrysostom himself and features above on UC71826. Other examples in the Petrie also use similar symbols, such as the “evil eye” – used to attract the envious looks of others which would otherwise injure the wearer. This is seen as a decorative device on the single bead strung into the red thread of UC51608, below.

Thus, the presence of red threads in the Petrie, preserved by the exceptional conditions in Egypt, reveals a social practice known of throughout Egypt and the Greek East from textual sources. Notably many of these artefacts were excavated from Roman cemeteries; it seems particularly appropriate that such protective devices were worn by the dead as they made their final journey to the afterlife.