Christmas in the Northern Hemisphere arrives in the heart of winter, invoking scenes of frost, bare trees, and monochrome colours. Yet it’s also the season we fill our homes with lush greenery and the rich smell of spices. Why are certain plants so tied to Christmas? What other meanings do they hold? And what festive flora are celebrated globally? Combining my love for ethnobotany and Christmas, I’ll dive into these questions, exploring the history of some iconic plants while touching on their ecology and conservation.

Some familiar flora

Whether you prefer a traditional tune while you “deck the halls with boughs of holly” or would rather join Bieber and “stand under the mistletoe”, it won’t be long before plants feature on any Christmas playlist.

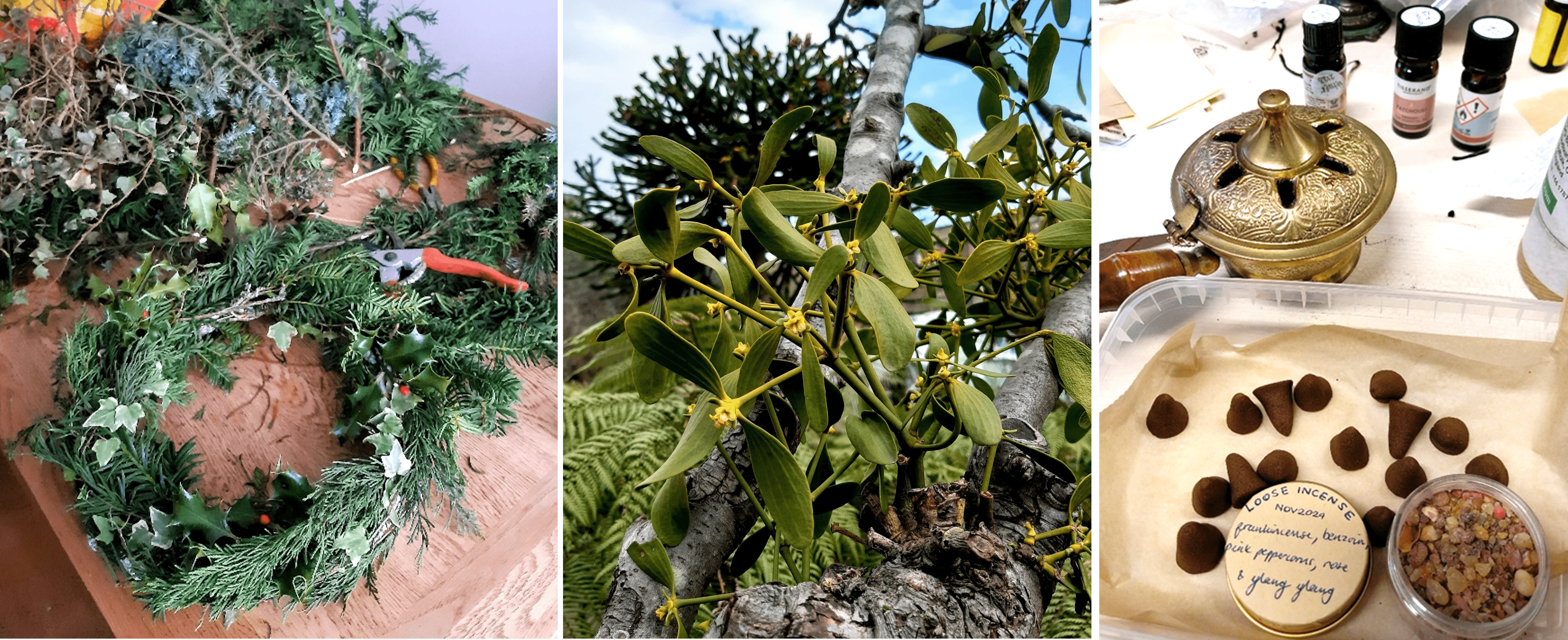

Evergreens like holly, ivy, and mistletoe have long carried deep symbolic meaning, including in pagan traditions. This continued with the spread of Christianity, where their evergreen leaves represent life after death. But their use as Christmas decor came with strict rules. Bringing evergreen branches indoors before Christmas Eve or leaving them up beyond Epiphany (6 January) was thought to invite bad luck. Meanwhile, felling a holly tree (Ilex aquifolium)—a plant so closely tied to the festivities that it was simply called “Christmas” in parts of England—was considered ominous, with holly often spared when hedgerows were cleared.

Beyond festive associations, these plants have had other uses. Accounts tell of holly and ivy (Hedera helix) being boiled with lard to treat chilblains and burns. Meanwhile, holly bark and mistletoe berries (Viscum album) have been used to make birdlime, a sticky glue used to trap small birds for food!

Despite their shared holiday status, these plants have distinct biologies. Holly is a tree or shrub naturally found in woodlands, ivy is a vine that clings to surfaces for support, and mistletoe is a partial parasite, relying on a host tree for nutrition.

Fit for royalty

The Bible tells of three kings baring gifts of gold, frankincense and myrrh to the infant Jesus. We all know gold is a precious metal, but did you know that frankincense and myrrh are both tree resins? This sticky liquid is extracted from trees in the Burseraceae family by cutting into the trunks, allowing it to seep out and harden before collection.

These resins have been prized for millennia for their rich scent. Myrrh, typically from the species (Commiphora myrrha), has been used in medicines, perfumes and incense. Meanwhile, frankincense, extracted from Boswellia trees, means “true incense” in Old French and is one of the world’s oldest traded commodities, even playing a role in Ancient Egyptian rituals such as mummification.

Both are still found in incense, perfumes, and essential oils today, providing vital income for communities in parts of the Horn of Africa, India, and the Middle East. However, over-harvesting, deforestation and climate change are pushing some Boswellia species towards extinction. Conservation projects, including sustainable harvesting initiatives, are ongoing, but conservationists highlight the need for awareness and support from major consumers.

A tropical Christmas

With Christmas celebrated in many parts of the world, a huge range of plants have gained yuletide associations. Ranging from palms to cacti and reflecting diverse cultural and ecological roots, a common feature is often a pop of red.

The Christmas palm (Adonidia merrillii), native to the Philippines, gets its English name from its bright red fruits. It’s now grown ornamentally worldwide, found along roads, in gardens, and even inside shopping malls. In its local range, the fruits have been used to chew on and for making beads.

The Christmas cactus (Schlumbergera species) is named for its bright flowers which bloom around the holiday period and are adapted for hummingbird pollination. Most houseplant varieties are hybrids, but their wild relatives in southeast Brazil face threats —six of the seven known species are globally endangered or vulnerable due to habitat loss and over-harvesting for trade.

Poinsettia (Euphorbia pulcherrima), now a staple in European Christmas decorations, have a long history in their native Mexico. Called cuetlaxōchitl in Nahuatl, it was cultivated by the Aztecs for its spiritual associations and use in fabric dyes and medicines. Today, it’s a popular Christmas plant across the Americas, known in Spanish as flor de nochebuena (Christmas Eve flower), with many coloured varieties available.

The symbolism and significance of Christmas plants are deeply tied to the meanings we’ve built around their natural traits. By uncovering these stories, I hope this blog adds to your enjoyment of festive greenery and brings a fresh perspective to help keep these ever-evolving traditions alive!

References

Friends and colleagues who have shared their plant knowledge over the years.

Bongers, F., et al. 2019 Frankincense in peril. Nature Sustainability. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-019-0322-2

Glaves, P. 2015. The holly and the ivy: how pagan practices found their way into Christmas. https://theconversation.com/the-holly-and-the-ivy-how-pagan-practices-found-their-way-into-christmas-52343

IUCN, 2024. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Schlumbergera. https://www.iucnredlist.org/search?query=Schlumbergera&searchType=species

Mabey, R., 1996. Flora Britannica. Random House.

Rojas-Sandoval, J. 2019. Adonidia merrillii (Christmas palm). https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/full/10.1079/cabicompendium.56193

Taylor, J.M., et al. 2011. The poinsettia: History and transformation. Chronica Horticulturae https://www.actahort.org/chronica/pdf/ch5103.pdf#page=23

Vickery, R. 2019. Vickery’s Folk Flora. An A-Z of Folklore and Uses of British and Irish Plants.