The last year has been turbulent for international cooperation, with growing erosion of commitments to protect and restore the natural world. High-profile cuts to international aid budgets have had cascading impacts on conservation worldwide (e.g., last year’s USAID cuts). Where these funding gaps have not been filled, many initiatives have been scaled back or stopped entirely.

But this isn’t a new phenomenon. Rather, these recent cuts reveal how precarious and short-lived many conservation initiatives are. This is the focus of our new article in Nature Ecology & Evolution: Conservation abandonment is a policy blind spot.

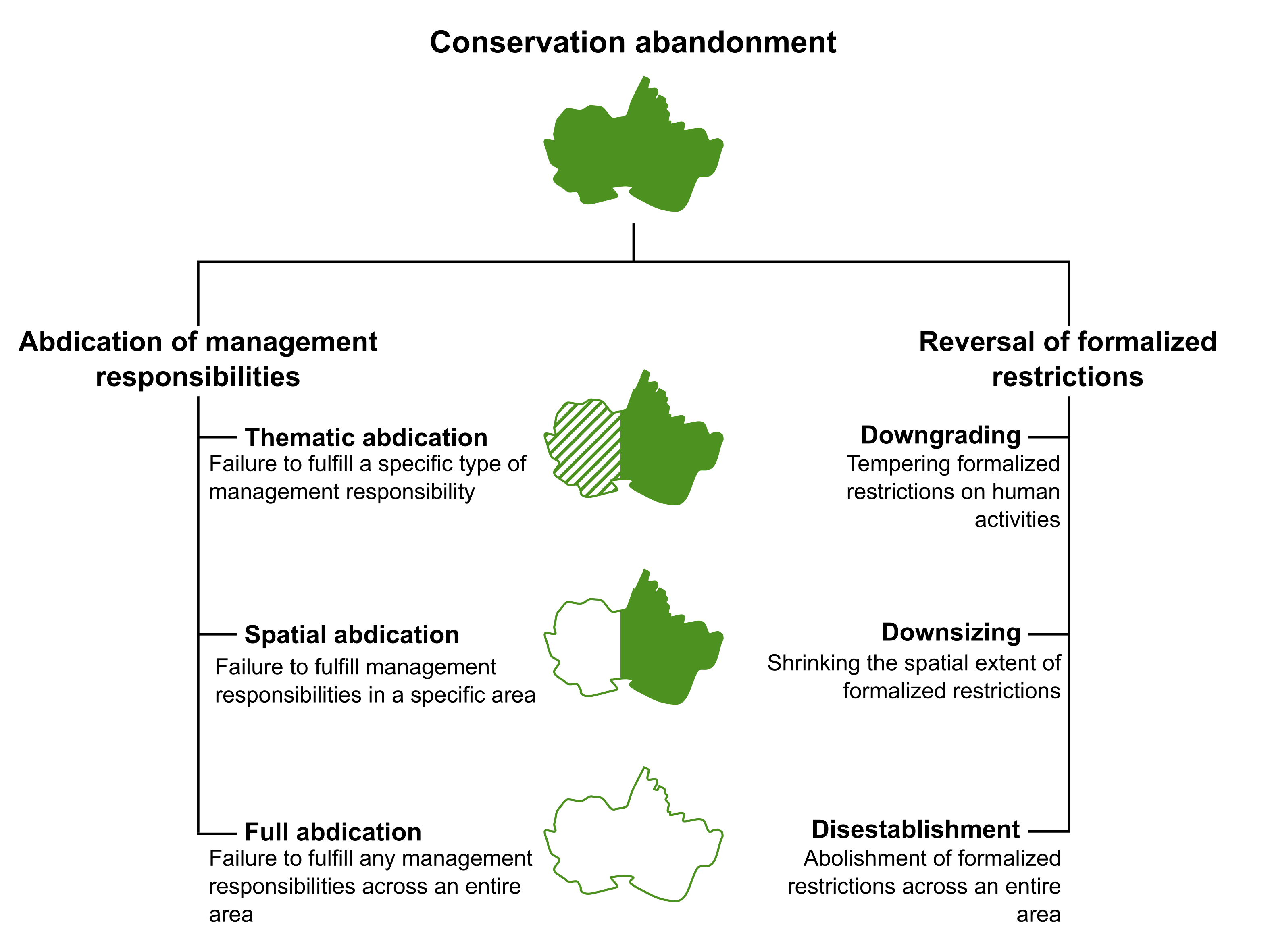

By “conservation abandonment”, we mean situations where conservation efforts are quietly or formally left to fail. This can include both informal abdication of management responsibilities (e.g., park managers failing to fulfil their duties) and formal rollback of protections (e.g., removal of environmental legislation). For example, during my PhD, I visited forests in Uganda where active Collaborative Forest Management agreements with communities existed on paper. However, many residents I spoke to either didn’t know about the initiative or didn’t realise it was still active, even though the agreements remained on paper. Somewhere along the lines, those responsible for maintaining and managing the initiative stopped doing so, illustrating an informal abdication of management responsibilities.

Abandonment is not always a bad thing. For instance, an irrevocably ineffective initiative should probably be terminated, as should those that actively harm people and their rights. Some have argued that core elements of mainstream conservation need to be rethought entirely and replaced with more experimental or alternative approaches. In other cases, an initiative may be terminated because it is no longer needed, for example, if the pressures it was designed to address have faded or disappeared.

Yet, in many cases, abandonment risks reversing hard-won gains and, if untracked, distorting perceptions of progress towards conservation goals. It also risks misallocating investment toward new conservation initiatives while underinvesting in the durability and effectiveness of existing ones. As a result, abandonment – particularly when unplanned, unjustified, and untracked – is often harmful.

Most research on conservation abandonment focuses on protected areas, such as national parks or reserves. For example, previous research found that, globally, protected areas totalling nearly the area of Greenland have been downgraded, downsized or degazetted since 1892 – a process known as PADDD. Similarly, the issue of “paper parks” – protected areas that remain in legislation but lack on-the-ground management – has been recognised for decades, though we still know relatively little about their prevalence, drivers, and consequences.

At the same time, conservation efforts extend well beyond just protected areas. The Global Biodiversity Framework – an international agreement adopted in 2022 – includes 23 targets that span a diverse range of goals, such as mitigating the introduction of invasive species, reducing biodiversity-harming pollution and promoting sustainable use of plants and wildlife. Meeting these targets will require a diverse mix of regulatory and voluntary initiatives. Yet, there is virtually no systematic understanding of the extent, patterns, or trends of abandonment across the range of conservation initiatives beyond protected areas.

It can sometimes be hard to tell if some initiative has been abandoned. For instance, in some contexts, specific projects and grants might end, while management activities persist and change locally over time. This issue is potentially exacerbated by the need to repackage the same management activities as novel innovations to secure funding and support.

But there are initiatives that clearly do persist over time. For instance, after graduating from Bangor University in 2012, I was lucky enough to secure a role at Ya’axché Conservation Trust in Belize. For a number of years, Ya’axché had been working with local farmers to produce shade-tolerant cacao that protects forest cover and biodiversity. Many farmers then sold their produce to Maya Mountain Cacao, a certified B Corp, which then exports the dried beans to speciality chocolate makers around the world. Nearly 15 years later, this model is still going strong, continuing to benefit farmers while protecting Belize’s Maya Golden Landscape.

This agroforestry model lasted, in part, because it offered clear, tangible benefits to those involved. This case starkly contrasts with the examples of Collaborative Forest Management agreements I mentioned earlier.

Often, practitioners on the ground are acutely aware of the issues of conservation abandonment and its impacts on people and nature. But this understanding does not always translate to policy and science. If conservation efforts are to last, we need to pay much closer attention to when and why they fade away. That means better tracking of abandonment and a clearer understanding of its causes. A greater focus on this issue is necessary, perhaps now more than ever, given the global turbulence that conservation will need to weather in the coming years.

_

For more information about Dr Thomas Pienkowski and his research, visit his profile.