Words by Adrian Smith, Emeritus Professor of Modern History at the University of Southampton.

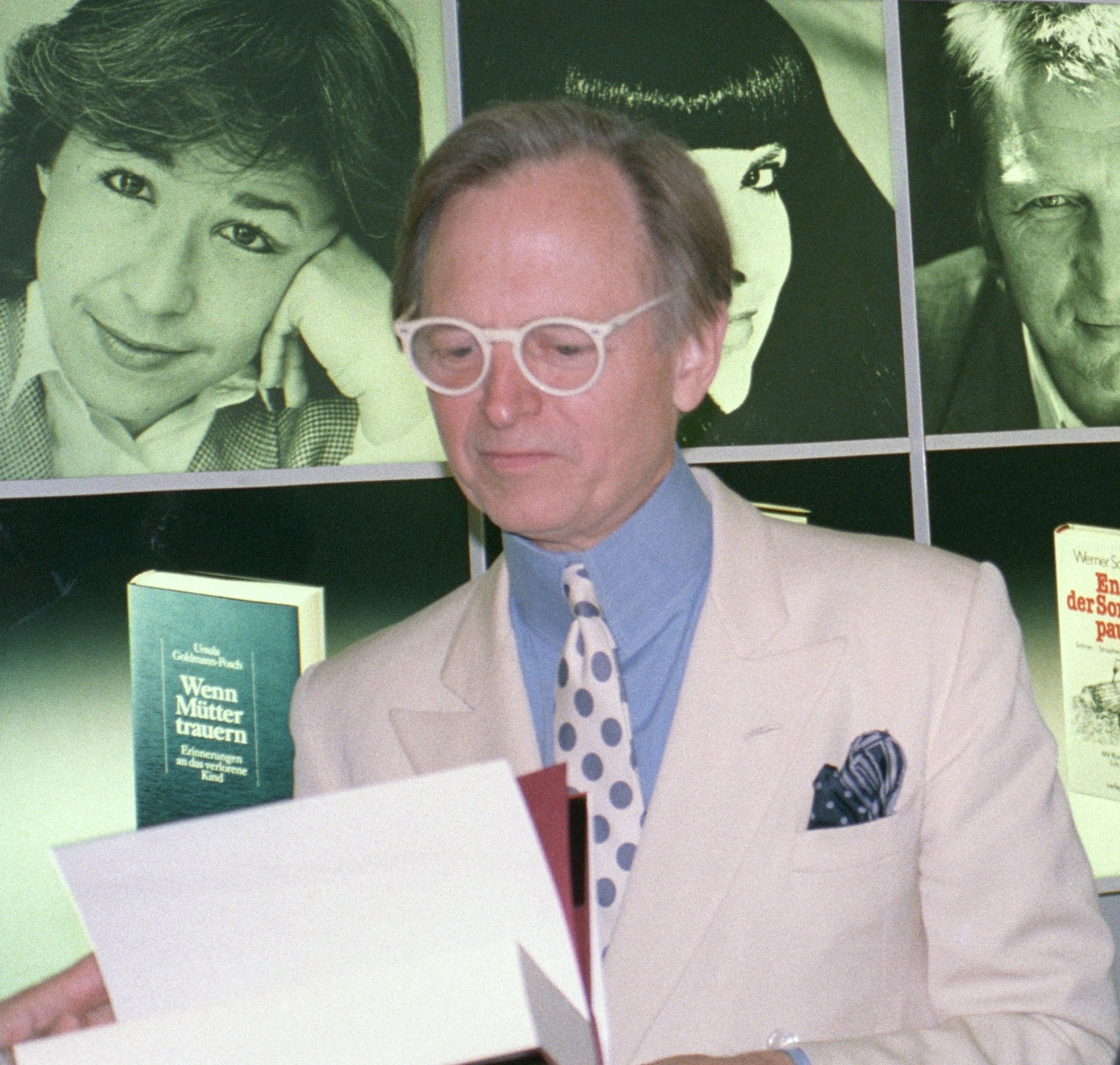

There he stood, silently acknowledging an awestruck audience as his host went through the formalities. In a mid-sixties lecture theatre showing its age and with a VIP dress code more Burton than bespoke, the tweed of the signature white suit positively glowed. Ah, the irony. Unsheathe the Montblanc Meisterstück 149 and dust down the Adler Universal 39 – who better than Tom Wolfe to capture the incongruity of Tom Wolfe in east Kent, far from his mid-Manhattan condo and the holiday home in The Hamptons? The date was Monday 17 October 1983, and the occasion the first of that year’s Eliot Memorial Lectures. Skipping Washington’s weekend premiere of The Right Stuff, Wolfe had flown direct to Heathrow, from where he was driven down to the then University of Kent at Canterbury (affectionately known as UKC, its abbreviation far in the future). He would deliver four lectures across four days, and on the Friday fly home to New York.

Except that Tom Wolfe never did write his very own Canterbury tale. What we do have are letters, lecture transcripts and memories (including mine) with which to reconstruct a forgotten episode in the life of someone forever synonymous with the ‘New Journalism’ of the 1960s. Needless to say, such lazy labelling scarcely acknowledges the versatility of a remarkable writer: from immersive reportage through fierce cultural criticism to decade-defining fiction. Tom Wolfe was also of course a remarkable talker, as he demonstrated night after night in Canterbury – and therein lay a problem.

Weighed down with awards for journalism (three big prizes inside eighteen months), early-eighties Tom Wolfe was on a roll. Reagan was in the White House, and with Wolfe joined at Rolling Stone by iconoclastic writers like PJ O’Rourke sharp-witted conservatism was cool. Published in 1979, Wolfe’s leftfield history of NASA’s Mercury programme, The Right Stuff, was his breakthrough book. He gained mass readership, and a level of gravitas previously absent. Critics loved Philip Kaufman’s star-studded adaptation, and although the film lost money its technical brilliance earned it four Oscars in April 1984. In the decade prior to the Academy Awards Wolfe had lauded Chuck Yeager over the disempowered space jocks in The Right Stuff, taken on the New York art establishment in The Painted Word, shredded Beltway players and power brokers in Mauve Gloves & Madmen, Clutter & Vine, and excoriated the condition of contemporary buildings in From Bauhaus to Our House.

It’s easy to see why From Bauhaus to Our House is out of print and largely forgotten. An all guns blazing attack on twentieth-century architecture’s unreserved embrace of modernist fads, fashions and fundamentals, this is a polemic of two halves – it’s no surprise to learn that the text first appeared in successive issues of Harper’s Magazine. The Painted Word had occupied only a single issue, Harper’s readers digesting a relentless intellectual assault upon American modern art and its abstruse evangelists. Both books share a common cultural target, and the epicentre of their loathing is the Museum of Modern Art: The Painted Word questioned MOMA’s collection policy and From Bauhaus to Our House its very existence.

The early chapters of From Bauhaus to Our House echo The Painted Word’s dismissal of the contemporary art world as smug, elitist, metropolitan and indifferent to popular taste: even before Walter Gropius and his Bauhaus acolytes arrived in the United States the nation’s architects were in thrall to an ‘International Style’ that rendered all buildings box-like, boring and dismissive of ideologically-offensive ‘bourgeois’ decoration. It’s a ferociously argued polemic but, as befits Tom Wolfe in high dudgeon, every sentence fizzes; yes, there are few laughs, but there’s every reason to keep reading. The same can’t be said for the later chapters, where Wolfe demonstrates the breadth of his research into contemporary architecture’s ceaseless clash of cultures, theories and egos – he’s read everything, however obtuse or obscure, and sat in on every discussion platform, however tedious and mind-numbing. Page after page of relentlessly waging a culture war forty years ahead of its time surely drove Harper’s readers to seek relief in the fashion shoots and society gossip columns.

Not that his publisher was deterred by Wolfe’s textual critique of competing theories or his mocking of modernist excesses far beyond the drawing board (the giants of the avant-garde’s greatest triumphs, Wolfe suggested, were too often little more than a blueprint, a half-finished score or an embryonic ballet chart). Farrar, Straus & Giroux published the text in book form at the end of 1981. The Painted Word had appeared six years earlier, and like its successor made only modest profits for one of New York’s most august publishers: Tom Wolfe’s royalties came largely from paperback sales, courtesy of Bantam. For publisher Roger Straus his most flamboyant author gave kudos to the company, but he wasn’t a big earner.

Both of Wolfe’s polemics on art and architecture shaped the content of his Canterbury talks. Indeed, anyone familiar with the books might not have returned after the second night. It’s ironic that the idea of Tom Wolfe giving the Eliot Memorial Lectures arose out of his meeting Stephen Bayley. Bayley had ambitions to quit his university post and forge a second career as a design critic and cultural commentator. He first met Wolfe in London at a 1979 RIBA conference and twelve months later interviewed him for Little Boxes, a BBC2 Horizon documentary on contemporary design. Wolfe championed Bayley’s books, entertaining him whenever he visited New York. The two men had hit it off from the start, not least because they shared a mutual distaste for campus life. In From Bauhaus to Our House Wolfe is unsparing in his disparagement of American universities, from Ivy League behemoth to humblest community college: the fiercest criticism is reserved for Yale, its featureless ‘structures’ exemplifying the worst of mid-century modernism’s ‘compound’ thinking. On his website Stephen Bayley thanks Terence Conran for ‘rescuing me from the tedium of provincial academe,’ and over the years he has displayed little affection for British universities and the people who teach in them. This deep scepticism clearly dates from his experience at Kent in the late ’seventies teaching history of art – he scarcely disguised his dislike of UKC and yet he felt warm affection for several colleagues, not least the philosopher Dan Taylor.

The late Dan Taylor was Master of Eliot College, and as such responsible for organising and hosting the Eliot Memorial Lectures; a task he positively relished. Although the early aping of Oxbridge traditions was long gone, Kent in the early ’eighties remained a collegiate university. The four original colleges retained their distinctive identities, but the masters (male and female) were no longer marquee signings; the likes of Dan Taylor lacked their predecessors’ academic cachet (Irish historian FSL Lyons had quit Eliot to become Provost of Trinity College Dublin) but they ran a tight ship, enjoying a privileged, relatively stress-free job. One unique privilege for the Master of Eliot was hosting for four or five days each year a leading scholar or well-known writer; which for Dan Taylor encompassed the likes of Asa Briggs, Bernard Williams and Jonathan Miller.

Its dining hall window offering a spectacular view of Canterbury and the cathedral, Eliot College was – and is – an impressive architectural presence. The quality of build belies the speed with which UKC’s inaugural college was constructed: two years from foundation stone to receiving its first students in September 1965. Nine months earlier the death of TS Eliot had prompted the University’s founding fathers to approach his widow for what today would be labelled naming rights. Valerie Eliot gave her permission for ‘Eliot College’, and for a high-profile annual series of lectures to commemorate her husband. TS Eliot was synonymous with Faber & Faber, and the company happily agreed to sponsor – and to publish – the ‘Eliot Memorial Lectures’. Faber’s influence was obvious in the choice of speakers, from W.H. Auden in 1967 through to Tom Paulin in 1996, the year the original format ended. Auden’s lectures appeared as Secondary Worlds, with a dedication to Mrs Eliot, but Faber’s involvement was based more on goodwill than any commercial consideration. The exception to the rule was the fourth speaker in the series, George Steiner, whose much publicised reflections on the Holocaust ensured healthy sales for In Bluebeard’s Castle: Some Notes Towards The Redefinition of Culture.

However, publication was never de rigueur. Success setting The Waste Land to music made Anthony Burgess seem an ideal choice in 1980. He gave a bravura performance at the piano, but what proved perfect for Radio 3 was deemed inappropriate as a book. Valerie Eliot found the first lecture’s damning reappraisal of Eliot’s poetry deeply offensive: she stormed out of the Cornwallis Lecture Theatre and went straight back to London. However, she was back the following year and in 1982, before being guest of honour at a symposium in May 1983 to mark the lecture series’ fifteenth birthday: Remembering Mr Eliot saw Stephen Spender lead a galaxy of Faber authors in praise of ‘Old Possum’.

Faber & Faber – in the form of chairman Matthew Evans and senior editor Robert McCrum – shared the University’s wish to attract high profile, low maintenance speakers. All parties were eager to avoid another Burgess-type scandal, so Dan Taylor couldn’t believe his luck when Tom Wolfe said yes to Stephen Bayley’s suggestion that he deliver the Eliot Memorial Lectures. Yes, Wolfe dressed flamboyantly and clearly had a sharp tongue, but he gave every impression that he would play by the rules. Crucially, he could bring in large numbers at a time when the recruitment of big names was flagging (Metropolitan Anthony of Sourozh/Anthony Bloom was a heavyweight theologian, but it’s hard to believe the 1982 lectures drew large audiences). An exchange of correspondence across the first half of 1980 saw Taylor brief Wolfe and, with help from Bayley in the Big Apple, secure his presence in Canterbury three years hence. Wolfe told Taylor that he saw the lectures ‘as a wonderful opportunity for me to try to pull together in some systematic fashion many thoughts that I have struggled with over the past twenty years about literature & life & times,’ and then promptly forgot about them.

In the autumn of 1982 Taylor reminded Wolfe that they were due to meet the following year, and after some effort secured agreement on mid-October. However, it took Roger Straus, the President of Farar, Straus & Giroux, to spell out what this commitment involved. This was at a dinner with Wolfe and his wife in November 1982, after which Straus confided to Robert McCrum that their respective publishing houses needed to act quickly if they hoped for a book akin to The Painted Word. Not that Wolfe was in any way hostile to the idea: ‘He is a long way from finishing his new work, a novel, and I know that this interim book would please him…as a small money-producing machine.’ Suffering from writer’s block, Wolfe was in fact a very long way from finishing what would become The Bonfire of the Vanities, so a nice little earner requiring minimal effort would help sustain a high-end lifestyle he could scarcely afford. Furthermore, he was getting an all-expenses paid trip to England, and a £500 fee. Urged on by McCrum, Dan Taylor reminded Wolf exactly what was required, and of the need for a series title and a title for each of the four lectures.

Taylor, by now experienced in handling big egos, was a master of the polite reminder. Finally, in late June he secured the necessary information, with Wolfe confiding his hope that ‘the titles don’t sound too severe. I am having a good time preparing the talks, and I hope they will appeal to, if not let, sporting blood.’ The overall title was ‘The Social Psychology of the Arts’, with a rider to the lecture list noting that ‘The words ‘Art’ ‘Artists’ etc in these titles refer also to Literature.’ Wolfe had insisted on booking his own flights, but all other arrangements were out of his hands: Faber would chauffeur him to and from Heathrow, and he would be staying on campus in the Master’s flat; dinner would be at High Table (in reality a private dining room) or courtesy of Canterbury’s celebrity chef Michael Waterfield (‘a good cook and a very civilised man’). Although Faber & Faber were footing the bill, Taylor never copied McCrum or series administrator Andrew Franklin into his correspondence with Wolfe; in a pre-email era why would he?

There was no chance of Tom Wolfe idling away his free time with a visit to Becket’s tomb or tea in the Butter Market. Between them Dan Taylor and the Faber publicity team filled his days with faculty lunches, an open session with students and a succession of interviews. The Sunday Times and the Sunday Telegraph lined up to profile Wolfe, as did the UK edition of Vogue – Lord Snowdon was scheduled to join Lucy Hughes-Hallett for a photo shoot and an interview. The University’s guest list of town and gown dignitaries looked positively Pooterish when combined with the Faber publicists’ power list of early ’eighties movers and shakers. In practice few residents of Hampstead and Islington drove down the M2 to hear Tom Wolfe, and those that did were only present for the first lecture and the reception. Turn out was respectable for the second lecture but it was obvious that many present the previous evening had returned to London. Front row seats were full again on the Wednesday night with Matthew Evans hosting FS & G’s Roger Straus and literary agent Deborah Rogers – they, their partners and Wolfe were then whisked away by Dan Taylor to eat at Michael Waterfield’s riverside restaurant. Andrew Franklin ensured a decent audience for the last night but one notable absentee was Robert McCrum, the maestro of proceedings being away in Australia. An initial healthy representation from the city council and the Cathedral had melted away across the week but not university staff, or indeed students.

Dan Taylor’s short, sparky introduction signalled why students would keep coming back – OK so he wears a three-piece suit, but Tom Wolfe has a direct line into ‘unrecognized subcultures of American life with their associated art and artefacts, objects of worship, ritual dances, totems and symbols. And what sub-cultures! Gamblers and Builders of Las Vegas, Abstract Artists and their patrons. Hot Rodders, Demolition Derbiests, Custom Car Creators, the brief but poignant coalescence of New York chic and the Black Panthers.’ Wolfe’s capacity to surf and strafe the zeitgeist, the power of his personality and even his mode of dress pulled listeners back night after night. He looked great, but he didn’t sound great. The conversational style of delivery and the Virginia man of letters voice worked well at the outset, but by the second lecture he was struggling with laryngitis; so much so that Taylor intended cancelling the event until at the last moment Wolfe croaked the show must go on. Delivery as much as content may explain why the BBC never broadcast the lectures on Radio 3. Tom Sutcliffe, then a young radio producer, had acquired permission from both Faber and UKC to record Wolfe. Today a familiar voice on Radio 4, Sutcliffe has no recollection of visiting Canterbury, and the recordings that do exist are clearly in-house and of poor quality.

The BBC did receive a copy of the lecture transcripts; according to Taylor successive typists struggled to interpret – or rather misinterpret – Wolfe’s multiple cultural references, but by Christmas the job was done (this was clearly a thankless task and poorly rewarded, but it’s hard not to smile at so much unintentional humour). The first lecture, on ‘The Natural History of the Contemporary Artist’, generated a lot of laughs, not least because the speaker was strikingly different from so many of his sober, sombre predecessors (having said that, were series veterans comparing him with Jonathan Miller, a performer rare in combining wit and gravitas?). Not for the last time Wolfe leaned heavily on The Painted Word, riffing for long stretches at a time on the cultural geography of Soho, the gurus and gallery fixers of downtown New York, and the vacuity of tyro artists desperate for recognition. His remarks were strikingly combative, not least his dismissal of Robert Hughes and John Russell. This was a clever observer of absurdity working an audience, and my recollection is that it worked; but on paper his remarks read like a jaundiced middle-aged man sounding off. Dan Taylor had promised us that, ‘Sometimes he is critical, even sharp; more often he celebrates varieties of life and art and their uncelebrated exponents. Always he is witty, elegant, accurate and generous.’ Well, witty yes – and on balance elegant and accurate – but generous most definitely not. The same could be said for the three lectures that followed.

Taylor and the laryngitis-stricken Wolfe each apologised for the brevity of ‘The Social Position of Artistic Styles’, but as it transpired the second lecture wasn’t that much shorter than the first. Here it transpired was a restatement of the ‘New Journalism’ manifesto. Thus Wolfe began in biographical mode recalling how awful he found living with Ken Kesey and his Merry Pranksters, but how necessary it had been if immersive reporting was to keep alive the four great devices of realism – ‘scene by scene construction, extended realistic dialogue, the notion of status details, and the use of point of view’ – at a time when modernism and experimentalism had destroyed the fiction of Dickens and Somerset Maugham (one of Wolfe’s unfashionable heroes): ‘these devices which were stumbled upon and invented by people like Richardson and Fielding in the 18th century were an invention to jog human memory in ways that caused the individual to relive experiences and I for one cannot understand how any writer once having tapped that power could ever voluntarily abandon it.’ In railing against a metropolitan elite that consciously set out to destroy Dickens’s credibility as a ‘writer of the people’, and in bizarrely insisting that the Oxbridge tutorial was to blame for a plethora of young British essayists but a dearth of young British novelists, Wolfe demonstrated his ignorance of the contemporary literary scene this side of the Atlantic, and his readiness to wage culture wars in a fashion all too familiar today. Once more we saw the combative tone, as in the NYRB’s founders stocking the paper ‘like a trout pond with British writers…Very soon the New York Review of Books became known as the London Review of Bores,’ its editor Bob Silvers cultivating ‘the best mid-Atlantic accent…it almost reaches the Welsh coast.’ Yes we all laughed, but on paper few gags stand the test of time. With hindsight, however, we can see Wolfe working out the ideas that shaped The Bonfire of the Vanities – if any Victorian author deserved a name check it was surely the Trollope of The Way We Were.

On Wednesday night, with his voice partially restored and special guests filling row A, Wolfe confided to his audience that ‘The Political Décor of the Artist’ was a subject ‘particularly close to my heart.’ A veritable tour de force which took in everyone from Antonio Gramsci to Eldridge Cleaver, Giangiacomo Feltrinelli to AJP Taylor, the lecture lambasted ideologically naive fellow travellers stranded by Stalinism and their Cold War successors: the misguided liberals of ‘radical chic’ who deliberately ignored the community activism taking place all around them. This was a bravura performance, and yet in written form the over long riffs and digressions highlight a now familiar absence of focus and intellectual coherence. There was a heavy dependence on From Bauhaus to Our House, but fashionable architects got off lightly as Wolfe had bigger fish to fry. Easy targets ranged from French cultural theory (‘mannerist Marxism’) to Italian cinema (at lavish coke-fuelled premiere parties Armani-suited directors declared their new films’ working-class credentials); the likes of the newly disgraced Anthony Blunt or the Nation’s editor Victor Navaski wore the ‘amulet of proletarianism’ while avoiding any contact with actual workers. Wolfe’s heroes were few and far between – step forward Alexander Solzhenitsyn and, surprisingly, Susan Sontag. In conclusion he declared Pol Pot to be ‘perhaps the most rational leader of the 20th century,’ because he had uncompromisingly carried out a blueprint for revolutionary terror learnt in Paris decades earlier. With his audience either in shock or asleep Wolfe ended with a contrived joke that conflated punk rock and The Communist Manifesto. Cue long applause, but no standing ovation.

‘The Social Uses of Contemporary Art’ (why ‘Art has become the religion of the educated classes in the West’) was a lecture too far. Wolfe should have quit the night before while he was still ahead. Many of the hard-core faithful present on the last night would have read The Painted Word and/or From Bauhaus to Our House, and therefore been familiar with much of what Wolfe had to say. To be fair he saved one or two great stories until the end, most memorably his recollection of the woman listening to the exhibition commentary on her Walkman who halfway through MOMA’s Picasso retrospective loudly protested, ‘But this isn’t his Blue Period!’. For all the sardonic observations on Manhattan cultural malarkey Wolfe did have some interesting things to say. He explained for a non-American audience the East Coast ‘hierarchy of museum giving’, and he described how the Vietnam War Memorial’s designers ignored vets’ suggestions for an easily traceable listing of dead comrades. But what of today’s controversies, as seen by Wolfe four decades back? Would, for example, contemporary environmentalists hail his attack on Exxon sponsorship of PBS TV as a prescient recognition of ‘greenwashing’? The ‘Black Lives Matter’ movement would surely be appalled by Wolfe’s defence of statue building as a means of uniting communities, not least in his native Richmond: amid huge controversy the Virginia state capital’s statue of Robert E. Lee was removed from its plinth in September 2021; had he still been alive Wolfe would surely have insisted the Lee Monument remain in place. Tom Wolfe and cancel culture was a collision only narrowly avoided – he died in 2018. Back in October 1983, the lecture’s final fifteen minutes constituted a rehash of the conclusion in From Bauhaus to Our House (in summation, ‘Western culture is in a severe crisis of its own making, believe me!’), but the closing remarks were gracious, stylish and clear evidence of how Wolfe could work a room, even one as big as Cornwallis – no one escaped his gratitude, not least Dan and Matilda Taylor.

The following afternoon Dan and Matilda waved goodbye to their guest; three hours later Wolfe was in Terminal 3 awaiting Flight BA195 to JFK. It’s clear from subsequent correspondence that Dan and Tom had got on really well. Taylor was warm in his appreciation of Wolfe’s overall performance: ‘You gave everybody a lot to think about and a great deal of pleasure and this place certainly needs stimulation [!!].’ The two men would go on to swap news about families, health issues and the weather. Wolfe by early 1984 had received transcripts and cassette recordings, but not his fee. Mortified at the University’s failure to reimburse his new friend, and with sterling worth less against the dollar than in October, Taylor secured an immediate payment at the previous autumn’s rate of exchange.

Taylor had already passed on to Faber & Faber Wolfe’s claim for a single flight from Washington to London and a single flight home to New York. Dan confided to Tom that ‘Matthew Evans went a little pale when he heard you had arrived by Concorde but it will be good experience for him.’ Faber’s chairman was more than ‘a little pale’ when asked to sign off a claim for $3,988 [£2,624 – £11,100 today]. Wolfe’s effrontery would enter company legend, not least as it was already clear there could be no book. The lectures would have to be drastically edited, and rewritten to avoid replicating much of The Painted Word and From Bauhaus to Our House. Focused on writing the magnum opus, Wolfe wasn’t interested in turning his random notes into a readable, marketable text – he wasn’t that short of money (the catalogue guide to Wolfe’s papers in New York Public Library confirms that only late in life did he start to write out lectures).

Dan Taylor hosted one more speaker before his second term as college master ended. The lecture series carried on, with Seamus Heaney delivering a memorable performance in 1986 (the lectures were published in Heaney’s second prose collection, The Government of The Tongue). Yet year by year the Kent campus was losing its distinctive collegiate identity. Students and lecturers – by now concentrated in departments – no longer strongly identified with their respective colleges. With Faber’s interest flagging, and Valerie Eliot well into her seventies, the Eliot Memorial Lectures had less significance for younger academics. Unwanted controversy surrounding the choice of Tom Paulin for the 1996 lectures saw all parties agree that the series had run its course. Henceforth the T.S. Eliot Memorial Lecture was a one-off occasion and no longer a fixed event in the university calendar; publicity for speakers such as Marina Warner (2017) and Kamila Shamsie (2022) listed distinguished predecessors such as Heaney and Edward Said, but with no mention of Tom Wolfe. A Google search provides no evidence of a connection between Wolfe and the Eliot Memorial Lectures, nor does the NYPL’s on-line archival guide. However, a close reading of The Bonfire of the Vanities reveals the University of Kent to be expat journalist Peter Fallow’s alma mater (had the original text been serialised in The New Yorker and not Rolling Stone an assiduous fact-checker would have pointed out the unlikelihood of a sixteen year-old Fallow attending university, let alone one yet to open).

Viewing the Michael Lewis/Richard Dewey documentary Radical Wolfe it’s hard to imagine their smart, smooth, hugely photogenic, metropolitan dandy hunkering down in east Kent for a fall break (one can safely assume Wolfe had never heard of UKC until he met Stephen Bayley: what was it, Kent State’s year abroad annexe?). There is something surreal about Tom Wolfe – the polite Southern wordsmith masking a master of the character assassination – taking afternoon tea in the Master’s flat, touring the Templeman Library and quietly bemoaning British standards of dry cleaning. It’s striking that he never wrote about the experience – it’s hard to imagine Joan Didion passing up such a glorious opportunity to anatomize provincial English academia. Most likely Wolfe needed to prioritise the novel, but perhaps he shrank from satirising such generous and appreciative hosts. Making a few bucks out of Faber & Faber was one thing, but poking fun at Dan, his family and his colleagues was cheap and unworthy. Wolfe’s default target was the elite liberal with his or her supposedly warped social conscience, but this wasn’t the Columbia Steps or Harvard Yard. The Master of Eliot College embodied a conservative institution, the members of which were doing their best to educate and to support young people at an impressionable age. This might have been a deeply patronising view of the Eliot Senior Common Room, let alone their students, but I suspect it explains why Wolfe wandered around campus with a permanently wry smile on his face – ‘I’m hanging out with the little guys and, hey you know what, it’s fun!’.

Thank you to Stephen Bayley, Robert McCrum, Tom Sutcliffe, Henry Claridge and Beth Astridge, University Archivist at the University of Kent.

Adrian Smith is Emeritus Professor of Modern History at the University of Southampton.