Context

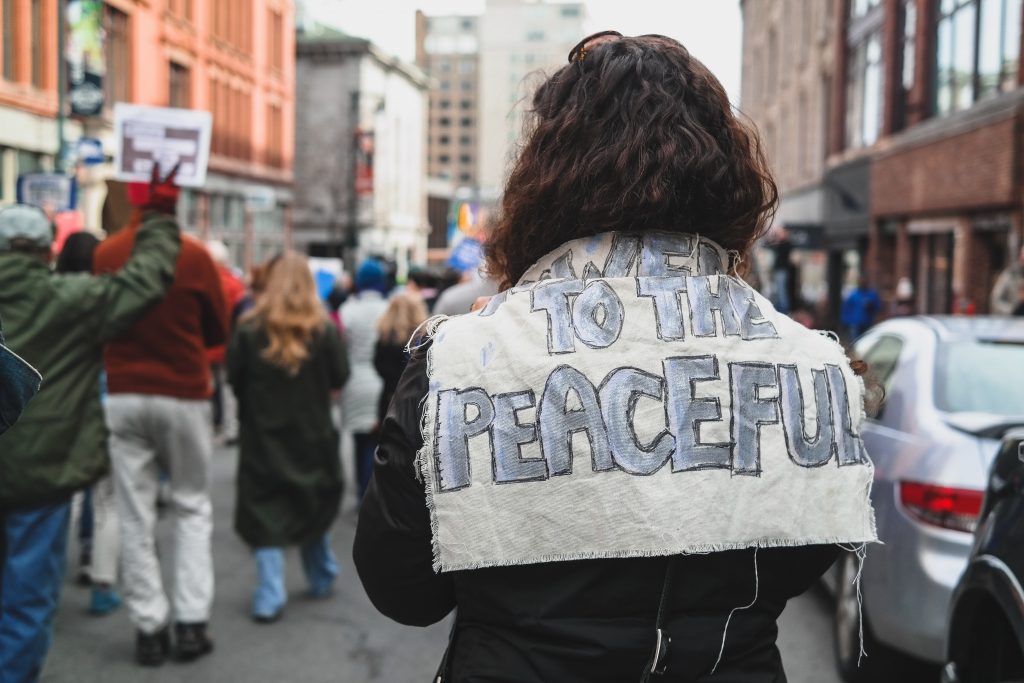

From time to time the police have to deal with a situation in which one or a few persons exercising their right to engage in peaceful public protest attract a threat of violence and public disorder emanating from a much larger group of persons opposed to the protest. If the police intervene to avert the threat of violence by removing the few peaceful protestors, they risk being accused of favouring the more aggressive majority over the minority’s right to protest peacefully. They may also be accused of being politically or culturally biased in the favour of the majority and hostile to the minority.

Historically, the UK courts have afforded the police a broad latitude in the use of their coercive powers to quell or prevent public disorder in such circumstances. They have not always been consistent or steadfast in upholding the rights of peaceful protestors against more aggressive opponents. In recent decades, however, the courts have been placing more emphasis on the importance of upholding the former’s right to freedom of expression over the interests of police expediency. A few weeks ago, the Canadian Supreme Court had to engage with this issue in Fleming v Ontario [2019] SCC 45. It was asked to decide whether the common law in Canada recognised a police power to arrest a peaceful protestor in order to prevent a threatened breach of the peace from other persons angered by the protest.

The Facts

‘Six Nations’ protestors had occupied a piece of Crown land in Caledonia, Ontario, in the course of a long running land dispute between them and the Crown. Counter-protests by opposing groups had sparked violence in the past. On this occasion, the counter-protestors decided to hold a ‘flag rally’ in the vicinity of the occupied land. The police plan for dealing with the potential for disorder entailed keeping the rival protestors apart. To this end they informed the ‘flag rally’ protestors that they were not to enter the occupied land.

On the day of the ‘flag rally’ protest, a police patrol encountered the complainant carrying a Canadian flag on the public road adjacent to the occupied land. They approached him with a view to forming a barrier between him and the ‘Six Nations’ protestors. He sought to avoid the patrol by entering onto the occupied land where he was about to be confronted by some of the ‘Six Nations’ protestors. A police officer told him that he was under arrest to prevent a breach of the peace. When he refused to drop the flag, he was wrestled to the ground, handcuffed and taken away. He was detained in a police cell for over two hours before being released.

The complainant sued the Province of Ontario and the police officers for damages for assault and battery, wrongful arrest and false imprisonment, and for breach of rights under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. He succeeded at trial, lost in the Court of Appeal from which he appealed to the Supreme Court.

Critically, the police defence throughout was that they had been exercising a common law power of arrest to prevent an anticipated breach of the peace. A primary issue for the Supreme Court, therefore, was whether the common law recognised a police power of summary arrest to prevent an anticipated breach of the peace, even though the person arrested was not acting unlawfully at the time and was not personally threatening a breach of the peace. The Supreme decided unanimously that there was no such common law power. Accordingly, it upheld the appeal and awarded the complainant Can$140,000 and costs totalling almost Can$200,000.

Ancillary Powers Doctrine

At the outset, the Court noted that in discharging their important duties in a free and democratic society, the police will have to interfere with individual liberty from time to time. It is also firmly established, however, that upholding the rule of law requires strict limits on police powers to interfere with the liberty or property of the person. In determining those limits, the Court applies the framework of the ‘ancillary powers doctrine’ originally laid down by the English Court of Criminal Appeal in R v Waterfield (1963).

In substance the doctrine asserts that police actions interfering with the liberty of the person are permitted at common law if they are reasonably necessary for the fulfilment of recognised police duties. In Canada, it has been used as the basis to recognise some significant and regularly used police powers at common law, including: temporary roadside checks to detect motorists driving under the influence of alcohol; investigative detentions; searches incident to arrest; home entries; sniffer dog searches; and safety searches.

Before applying the ancillary powers doctrine to recognise a common law power, the Court must define the police power being asserted and the liberty issues at stake. If the power prima facie interferes with the liberty of the individual, the doctrine is brought into play. In that event, the Court will have to establish whether the police action in question falls within the scope of a recognised police duty, and whether it involves a justifiable exercise of police powers associated with that duty. It is only if the asserted power satisfies these ‘ancillary powers’ requirements that it will be recognised at common law.

The asserted power

The asserted power in this case is a power of arrest to prevent an apprehended breach of the peace even though the person targeted is acting lawfully in the sense that he has not committed and is not about to commit an indictable offence or a breach of the peace. The essence of a breach of the peace is violence entailing actual or threatened harm to someone. Mere annoyance, insult or disruptive or unruly behaviour, stopping short of actual or threatened violence, is not sufficient. Clearly, the complainant in Fleming was not arrested for committing or being about to commit a breach of the peace. He was arrested in the belief that removing him from the scene might defuse the situation, avert the threat of violence from others and even protect the complainant himself from harm. In other words, it was essentially preventative in nature.

Interference with liberty

The Court had no difficulty in finding that the asserted power of arrest entailed a substantial interference with the liberty of the person. Placing a person under arrest takes away his or her freedom to move around in society free from State coercion. The use of force to effect the arrest is also an intrusion on the individual’s right to bodily integrity and security, and on the right to be free from the exercise of force by the State. In the particular circumstances of this case, the arrest power also entailed interference with the right to freedom of expression as guaranteed by the Canadian Charter on Rights and Freedoms. Taken as a whole, it directly impacted upon a “constellation of rights that are fundamental to individual freedom in our society.”

Valid police duty

With the scope of the power defined and the interference with liberty established, it remained for the Court to determine whether, in accordance with the ancillary powers doctrine, such a power would be justified for the purposes of fulfilling a valid police duty. The next question, therefore, is whether the asserted police power is linked to a valid police duty. The Court had no difficulty in answering that question in the affirmative. Preserving the peace, preventing crime and protecting life and property are firmly established as principal police duties at common law. Preventing breaches of the peace is clearly encompassed by those duties.

Justification

The more difficult question is whether the asserted power of arrest is justified or reasonably necessary for the purpose of fulfilling that duty. The Court noted that the standard justification must be commensurate with the fundamental rights at stake. To put it another way, there must be minimal impairment of the rights in question, and there must be proportionality between the object sought to be achieved by the power and the degree of interference with those rights.

The Court identified three reasons why the standard of justification for this particular power is especially stringent and difficult to satisfy. The first is that the power is expressly applied to someone who is not suspected of any criminal wrongdoing or even threatening to breach the peace. That contrasts with the norm in which arrest powers are, at most, directed at persons against whom there is a suspicion that they have committed, are committing, or might commit, a criminal offence. In the Court’s words, “[i]t would be difficult to overemphasise the extraordinary nature of this power”. It would “constitute a major restriction on the lawful actions of individuals in this country.” The Court also emphasised the importance of guarding against intrusions on the fundamental liberty of individuals who were neither accused nor suspected of committing a crime. Quoting from Lord Mance in the English case of Laporte (2006), it said that police preventive action should be focused on those who are acting disruptively, not on innocent third parties.

The second reason why the asserted power is subject to stringent justification is that it is preventative in nature. It is targeted at preventing a breach of the peace before breach has taken place. The Court acknowledged that the ancillary powers doctrine does not preclude the possibility of proactive police intervention in preserving the peace, preventing crime and protecting life and property. Where such actions intrude upon the liberty of the individual, however, courts must be very cautious to avoid authorising them on the basis of vague or overly permissive standards.

The third reason is that exercise of the asserted power is “evasive of review.” Since such an arrest does not normally result in the preferring of criminal charges, the person concerned is deprived of a forum to challenge its legality, other than through an expensive civil suit.

Taking all these factors together, it is clear that the standard of justification for extending the ancillary powers doctrine to the power asserted in this case will be onerous. The police will carry a heavy burden to establish that it is reasonably necessary.

Applying the doctrine

In applying the ancillary powers doctrine stringently to the asserted power, the Court proceeded on the basis that preserving the peace and protecting people from violence is an immensely important police duty. It also accepted that there may be exceptional circumstances in which some interference with liberty is required in order to discharge that duty. Arrest, however, is such an extreme intrusion on liberty that it can only be justified if it is necessary in order to prevent a breach of the peace from occurring. Where less invasive measures are available, they must be taken.

The Court could not conceive of circumstances in which a common law power of arrest would be required in order to prevent a threat of future violence from materialising. Other lesser options are available and should be taken. Under Canadian law, for example, it is an offence to restrict or wilfully obstruct or assault a police officer in the execution of his or her duty. This carries a statutory power of summary arrest. So, a police officer already has the power to defuse a potentially violent situation by less intrusive actions, such as giving instructions to one or more individuals to leave the scene or desist from specified conduct. Resistance or obstruction will amount to a criminal offence for which the individual can be arrested. In that event, however, the power of arrest is linked to an offence that has actually been committed, as distinct from lawful behaviour which may provoke others to resort to violence.

Given these other less intrusive options, the Court concluded that it was not reasonably necessary to recognise another common law power of arrest to prevent an anticipated breach of the peace. The mere fact that police action is effective in preventing a breach of the peace cannot be relied upon as a justification if it entails interference with the liberty of the individual. The test is whether it is reasonably necessary. If a breach of the peace can be achieved by an action that intrudes less on liberty, a more intrusive measure will not be reasonably necessary no matter how effective it may be. Sanctioning significant infringement on the liberty of the individual on the basis of its effectiveness is “a recipe for a police state, not a free and democratic society.”

Accordingly, the asserted common law power cannot be justified under the ancillary powers doctrine. There is no such power. Since the police relied on the asserted common law power to arrest the complainant, it follows that his arrest was unlawful.

Comment

On the face of it, the decision in Fleming may seem a significant victory for the right to liberty and freedom of expression over police power. It certainly represents a solid re-affirmation of the basic principle that police actions encroaching on the liberty of the individual must be based on established law. The fact that the common law in Canada does not recognise a police power to arrest an individual who is not acting unlawfully or threatening to act unlawfully will not cause surprise in the UK where decisions, such as that in Laporte (2006), have precluded premature police encroachments on liberty and freedom of expression in the name of public order. The common law does not permit the police to deprive a law-abiding individual of his liberty simply because they deem it expedient to do so in order to neutralise a future threat of violence from hostile third parties. This applies even where the complainant, as in Fleming, has provoked the threatened breach of the peace by his words or actions.

It does not follow that the decision in Fleming seriously restricts the tools available to the police to preserve the peace or maintain public order. The reality is that Canadian legislation (and common law), as in the United Kingdom and Ireland, confers the police with broad summary powers to maintain public order. In Fleming, the essential police error was a failure to proceed initially by taking action short of arrest to protect the complainant from the risk of violence provoked by his actions. Had they attempted to do that, and the complainant failed to cooperate, the police could have arrested him lawfully for obstruction of a police officer in the execution of his duty.

Finally, the decision in Fleming does not close off the possibility of a common law power of arrest where it is reasonably necessary to arrest a person acting lawfully because there are no lesser options at common law or in legislation to prevent violence from occurring. Given the wide availability of lesser options which should be used initially where possible, it will be a rare situation in which it will be necessary to resort to such an arrest as the first response. It is also worth noting that the decision in Fleming does not preclude the possibility of a common law police power to arrest an individual in order to prevent a breach of the peace, where it is the individual himself who is threatening to breach the peace. The Court declined to declare a position on that, preferring to leave it to another day when the issue arises for decision on the facts.

Download the November 2019 edition of Criminal Justice Notes