As the Black Lives Matter movement continues to provoke a necessary and painful reckoning with the slave trade, colonialism and their legacies in the wider British public memory, it’s timely to remember that British slave traders trafficked at least 2.6 million Africans to the Americas. [1] This brutal and violent trade was carried out for economic gain and many of its legacies persist. Yet, all too often, mentions of Britain’s slave trading past are met with the retort that Britain led the way in abolition, especially through British naval interventions against slave ships. A one-dimensional narrative of British interventions on the high seas against the slave ships of other nations can suit those seeking to project a public memory and contemporary image of a swashbuckling plucky island nation, but it is an incomplete history. What also needs to be emphasised is that during the first part of the nineteenth century the capture of a slave ship laden with slaves (also known by the objectifying term “re-captives”) [2] did not legally guarantee the freedom of individuals who were enslaved on board, [3] and such freedom, where granted, was constrained in a way that also brought economic benefits to Britain. And even when freedom was granted, further suffering had often first been heaped on these traumatised individuals while they were transported to a court that was able to adjudicate their plight. An overly simplistic image of British interventions on the high seas should not be deployed to whitewash the British slave trade, its effects and ongoing legacies

Remembering abolition

In 1807, the Abolition Act abolished British participation in the slave trade. Britain was not the first European state to abolish its slave trade and it is well documented that whatever the law on the books said, British involvement in the trade continued, [4] to say nothing of slavery itself which was not abolished in most parts of the British Empire until 1833. Even so, the British government turned its focus towards the slave trade carried out by nationals of other states. To this end, Royal naval ships engaged in a series of extremely controversial – and initially often internationally unlawful – detentions of foreign slave ships. These actions generated significant diplomatic and legal controversy in the early years of the nineteenth century. Eventually though, Britain was able to cajole, including through some significant financial inducements, a number of states to agree to a series of slave trade repression treaties. From 1817 onwards, some of these included the establishment of a series of Mixed Commissions on the Slave Trade. Mixed Commissions operated amongst contracting parties on a bilateral basis. They determined whether slave ships of contracting parties had been lawfully captured and detained. When a slave ship was captured, it, its crew and any re-captives on board were sailed to the nearest Mixed Commission which determined the fate of the ship and re-captives. Mixed Commissions at Sierra Leone were particularly active, and there are voluminous records at the National Archives, Kew dealing with these cases and the legal controversies they generated. They are a veritable treasure trove for anyone interested in understanding the role of law in abolition, and the impact of law on the lives of re-captives.

There is a lot of dispute about why the British government pushed for abolition internationally, and there are long-standing and well documented differences of opinion between those who emphasise humanitarian reasons and others who focus on economic concerns.[5] Understanding motivations for events can help us to understand historical change, but it is less helpful to a nation seeking to reckon with its past, unless we also consider the effect of the actions of those in power on those who were at their receiving end, those who are glossed over in the legal record and, still all too often in the public memory.

In cases where a ship had been lawfully captured, Mixed Commissions were empowered to emancipate re-captives found on board. The corollary of this was that where a slave ship was unlawfully captured the situation of re-captives was legally precarious. When remembering this period of slave trade abolition then it is important to remember that British interventions against slave ships did not legally guarantee the freedom of all re-captives on found on board captured slave ships.[6] As I explain in my recent book,[7] the treaties that Mixed Commissioners applied focused on determining whether slave ships were lawfully captured, rather than the rights of those enslaved. Complex rules in the treaties governed the circumstances in which the capture of a slave ship was considered lawful. Broadly, a slave ship was only lawfully captured if it had been illegally slave trading in the first place (and slave trade suppression treaties at this time still permitted slave trading in certain geographical areas for certain periods) and if it was captured and detained in an agreed geographical area, in a prescribed manner and under particular circumstances. These changed over the life of Mixed Commissions, but in practice slave traders had plenty of opportunities to argue that their ships had been unlawfully detained.

When a slave ship was captured by the British navy, individuals enslaved on board were therefore at risk that a Mixed Commission might order them to be returned to the master of the slave ship, with utterly disastrous consequences. This was unusual, but not unknown.

The Maria da Gloria

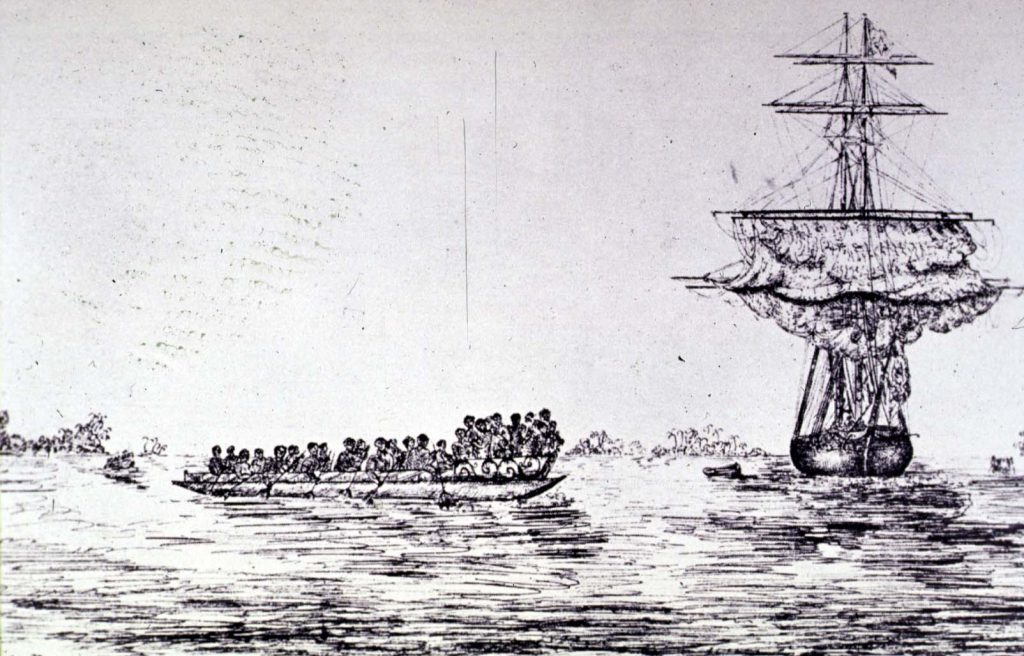

In November 1833, the British captured the Maria da Gloria just outside Rio harbour. Over 400 individuals who had been illegally trafficked were crammed on board. The British-Brazilian Mixed Commission, which was called on to adjudicate, felt itself unable to exercise jurisdiction over the ship because it considered the ship to be Portuguese.[8] So, the British captors sailed the ship to Sierra Leone with the surviving re-captives on board to find a court that could adjudicate. The unavoidable legal problem they and the re-captives faced when the case was brought before the British-Portuguese Mixed Commission in Sierra Leone was that the British had captured the Maria da Gloria south of the equator. The applicable British-Portuguese Treaty only allowed Portuguese ships to be captured north of the Equator. Even though the Maria da Gloria had been unlawfully slave trading, the British-Portuguese Mixed Commission felt compelled to order the Maria da Gloria and its human cargo to be returned to the master of the slave ship. On 9 April 1834, 240 surviving re-captives who were considered fit to travel were transported from Sierra Leone, a colony that the British had established for freed slaves, across the Atlantic for a third miserable passage to enslavement in Brazil.

Remembering that British interventions against slave ships resulted in the emancipation of enslaved individuals should not blind us to the fact that the position of re-captives on board captured slave ships could be legally precarious. Small wonder that there are examples of re-captives either escaping to the shore or effectively forcing the crew to land them, rather than remaining on captured slave ships moored in the harbour of Sierra Leone to wait for the outcome of a Mixed Commission judgment. In these cases, they effectively seized freedom for themselves. This is what happened in the Activo and Perpetuo Defensor Cases, two other cases in which re-captives had been illegally trafficked but transported on ships that had been captured by the Royal Navy outside the strict scope of the relevant treaty.[9]

The case of the Maria da Gloria haunts slave trade abolition. Those who emphasise the humanitarian causes and effects of British interventions might argue that it was exceptional. However, this loses sight of the fact that for all its horror and exceptional circumstances the Maria da Gloria provides a devastatingly perfect illustration of the way that the treaties on slave trade abolition agreed during this period focused on questions about lawful intervention and the property rights of slave and ship owners, and not any rights of those enslaved. This is further evident in the Perpetuo Defensor and Activo cases. For, strikingly, the solution eventually reached in these cases minimised the financial liabilities of the British resulting from the unlawful detention of slave ships south of the Equator. It did not do anything to safeguard the freedom of re-captives detained on illegally captured ships as a matter of general principle, even where they had been illegally trafficked. Although re-captives in the Activo and Perpetuo Defensor cases made it to the shore, others were not so lucky, as the Maria da Gloria shows.

British interventions and the construction of a public memory

What then might we make of this complex history? It is after all only one part of a much broader history of slave trade abolition. In the end of course the Navy and Mixed Commissioners could only go so far as the treaties allowed even if their interpretations stretched them on many occasions, and this came back to what states were willing to agree. The past cannot be captured one-dimensionally, but those who seek to project a proud history of slave trade abolition in the public memory do just that when they fail to acknowledge the ambiguities and limitations of slave trade abolition and the effects of these on the lives of enslaved Africans. Interventions against slave ships could leave re-captives in a legally precarious position and re-captives, even when liberated, were still displaced and likely traumatised. The public memory of slave trade abolition should instead also celebrate re-captives’ resilience and survival alongside the actions of the Royal Navy. It might also acknowledge the economic benefits slave trade abolition brought Britain. While liberated Africans were never compensated for their illegal enslavement, they were often subjected to various forms of coerced labour,[10] and many re-captives emancipated at Sierra Leone were recruited as indentured labourers to the British West Indies, especially after the abolition of slavery.[11] Britain’s intervention against slave ships did not – and could never have – redeemed the role the state played in the slave trade, but it also generated injustices of its own. Simplistic narratives about abolition in the public sphere do not do enough to acknowledge these injustices, and for lawyers that also includes acknowledging the role that the law played in them.

Dr Emily Haslam’s research interests lie in the field of international criminal law, specifically the treatment of victims and the role of civil society, and in international legal history. Her current research focuses on a history of slave trade repression in international criminal legal history.

[1] Hamilton and Shaikh, ‘Introduction’ in Hamilton and Salmon (eds) Slavery, Diplomacy and Empire: Britain and the Suppression of the Slave Trade, 1807–1975, (Sussex Academic Press 2012) at p. 2.

[2] Re-captives were slaves found on board ships captured by the Navy.

[3] Haslam, The Slave Trade, Abolition and the Long History of International Criminal Law: The Recaptive and the Victim (Routledge 2019).

[4] See further, for example, Sherwood, After Abolition: Britain and the Slave Trade Since 1807 (I. B. Tauris, 2007).

[5] See further for example, Williams, Capitalism and Slavery (Andre Deutsch Ltd 1964); Brown, Moral Capital: Foundations of British Abolitionism (North Carolina Press 2006).

[6] The treaties permitted the navies of both signatory states to detain slave ships, but interventions in practice were carried out by the British navy.

[7] Haslam, The Slave Trade, Abolition and the Long History of International Criminal Law: The Recaptive and the Victim (Routledge 2019).

[8] HM Commissioners to Palmerston, 22 March 1834, The National Archives (TNA): FO 84/149, 22 and Report of the Case of the Maria da Gloria, TNA: FO 84/149, 39.

[9] Hamilton to Canning, 12 October 1826, TNA: FO 84/49, 160 and accompanying Report of the case of the Perpetuo Defensor, TNA: FO 84/49, 167; HM Commissioners to Canning, 10 June 1826, TNA: FO 84/49, 84 and accompanying Report of the Case the Activo, TNA: FO 84/49, 88.

[10] Lovejoy, and Schwarz, ‘Sierra Leone in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries’, in Lovejoy and Schwarz (eds.), Slavery, Abolition and the Transition to Colonialism in Sierra Leone, (Africa World Press 2015) at p. 21

[11] Asiegbu, Slavery and the Politics of Liberation 1787-1861 (Longman 1969); Mahmud, ‘Cheaper than a Slave: Indentured Labor, Colonialism, And Capitalism’ (2013) 34 Whitter L. Rev. 215. So too were slave owners, and not slaves, compensated after the formal abolition of slavery in 1833, see further Hall, Draper, McClelland, Donnington and Lang, Legacies of British Slave Ownership: Colonial Slavery and the Formation of Victorian Britain (Cambridge University Press 2015). British taxes controversially continued to pay for the money borrowed to pay this compensation until 2015.