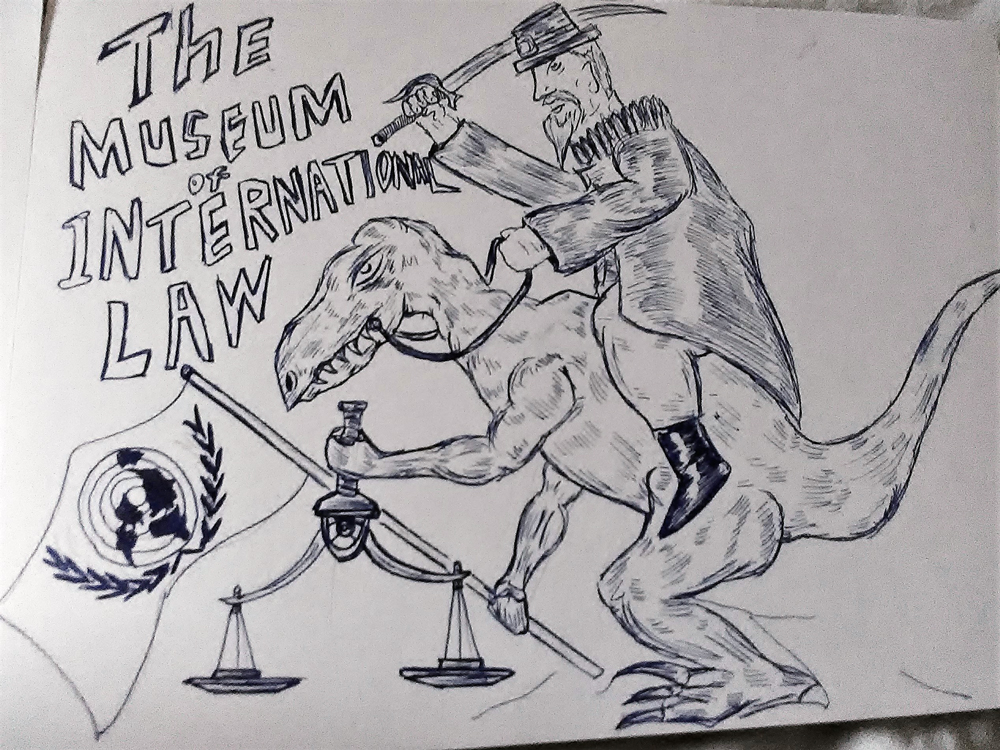

CeCIL hosted its first event of the Spring semester on Tuesday 30 January with a fascinating talk on an ongoing project entitled ‘The Museum of International Law.’

Unlike our typical lecture series featuring a single speaker, this event came in the form of a panel discussion featuring Qudsia Mirza from Birkbeck, John Strawson from the University of East London, and Kent Law School’s very own Emily Haslam and Sara Kendall. ‘The Museum of International Law’ project itself implores us to think about the ways we imagine how objects and artefacts are stored, displayed, and curated in a manner reflective of a larger cultural setting. In this way, museums are never simply an objective presentation of things, but rather they speak volumes about how a society situates itself in relation to others. This is especially the case when considering how the total collections of museums are almost always greater than what is actually visible in the exhibits, thus highlighting the reality that concealment is as much a part of museum curation as is display. In this way, the analogy of the museum forms a fitting analogy for how the individuals, events, and ideas that have shaped the development of international law are subject to similar practices of display, concealment, and curation. Given the recent turn to understanding the historical and ongoing experiences of those excluded by the mainstream narratives of international law, the medium of the museum has much to offer those seeking alternative forms of knowledge presentation within international law.

Qudsia’s talk on ’The Possibility of Memoralising Parition in Pakistan’ presented a rich array of the motivations, hopes, and tensions implicated in the campaign within Pakistan to memorialise the 1947 India-Pakistan Partition. Qudsia explained how a strong push for such a Partition monument has come from Pakistan’s women’s movement. This campaign is informed by a history where the disappearance, and later recovery, of women during the upheaval of the Partition forms a powerful narrative of Pakistani nationhood where women are vital in restoration of national honour. However, this campaign also implicates divisions within Pakistan’s women’s movement, for while it has traditionally consisted largely of liberal middle-class women who see a monument as an opportunity to present their story, a parallel movement has witnessed assertions by generally less affluent/more religious women who question the value of such a monument. Qudsia incisively noted that the forces driving these patterns of contestation over what is ostensibly an issue of national memorialisation are transnational in nature through their production of tensions between an ethos of international human rights associated with the traditionally liberal women’s movement and a countermovement asserting an alternative understanding of values rooted in the larger phenomenon of Islamic Revival.

John’s talk shifted the discussion from memorialising events of international legal significance, to what exhibits might actually be displayed within an actual ‘museum of international law.’ In a provocative talk entitled ‘George W Bush – A Publicist of International Law?’ questions were posed concerning the role of ostensibly villainous figures in contemporary imagination of international law. While the Administration’s orchestration of the Iraq War is commonly perceived as one of the most egregious international legal breaches in modern times, John turned our attention to the ways in which debate surrounding the legality of war helped to transform international law from an esoteric domain of expertise to a larger, grass-roots political and cultural discourse. In a deeply related capacity, while international law has long served as a means of enabling the exercise of political power, especially as it related to waging wars and building empires, the protests and public debates leading up to the 2003 invasion of Iraq contributed a great deal to building the image of international law as force restraining the exercise of power politics. Given this contribution, would it not be appropriate to display a portrait of George W Bush in the museum of international law?

Emily’s talk on ’Representation, Sacrifice, and the Museum of International Law’ provided a fascinating comparison concerning Britain’s involvement in contemporary armed conflicts. The first was the 2017 Iraq and Afghanistan Memorial which honoured British citizens who took part in the wars in these countries. What is notable about this memorial is that, in a departure from the predominant focus on the sacrifice of soldiers, this memorial explicitly commemorates health and humanitarian workers in addition to military personal. This is contrasted to an exhibit at Tate Britain where the artist Mark Wallinger recreated the 2001 protest created by the prominent antiwar protestor Brian Haw in Parliament Square.

Finally, Sara’s talk on ‘Curating Atrocity: Raoul Peck’s Lumumba: La Mort du Prophète’ tasked the audience with imagining the processes of curation and memorialisation through a medium beyond the space of the physical museum. Attention was turned to Raoul Peck’s film ‘Lumumba: La Mort du Prophete’ which confronts the legacy of Belgian activities in the mid-twentieth century Congo by locating its setting in contemporary Belgium. In doing so it offers an alternative curatorial practice on the question of guilt and responsibility through its depiction of the assassination of Congolese President Patrice Lumumba, and the larger violence of colonialism, as something that haunts Belgium in the here and now. This allows for a transcendence of the immediate context of Cold War Africa that both stretches back into the deeper history of colonisation and forward into the conscience of the contemporary colonial metropole.

In conclusion, the ‘Museum of International Law’ left us with no shortage of profound questions for how it is our practices of display, concealment, and curation strike at the very heart of international law as a discipline and profession. While there remains so much to be explored, Qudsia, John, Emily, and Sara, all in their own unique ways, provided profound insight in how we might undertake such a monumentally important task.