The following article is authored by Kent Law School PhD student Allison Lindner.

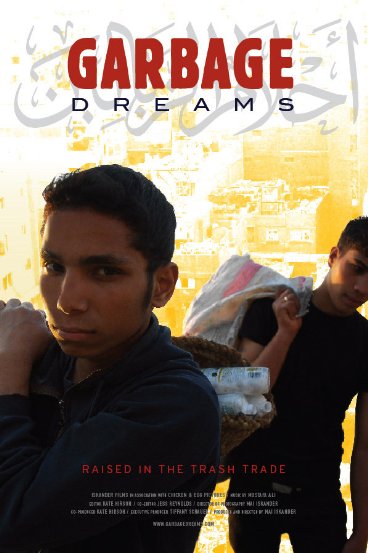

If you are interested in first hand accounts of how privatisation affects the lives of people at the margins in developing countries, you may be interested to watch Garbage Dreams. My doctoral research on waste pickers led me to this documentary directed by Mai Iskander, an Egyptian American film director. I am undertaking a socio-legal study of what happens to these people who sort and sell garbage informally for a living, when the spaces in which they work become privatised by multinational enterprises. This is very much the story of Garbage Dreams.

The film follows the lives of three young friends who work as ‘zaballeen’ (waste pickers in Arabic) in an informal settlement named Mukattam in Cairo. There is Osama, who has tried many jobs, hoping it will bring him respect from his community, yet he always winds up working in garbage. There is Nabil, who, content with his life, looks forward to getting married and being considered a real man. There is Adham, who has a bit of a temper but wants to modernise the recycling industry. They all see their fortunes dwindle when Cairo’s municipality opens its doors to foreign waste management companies in the mid-2000s. These young men have a refuge, the zaballeen community-run Recycling School, where they learn reading and writing, and of course, about recycling.

Technique analysis

Telling the story through the eyes of three teenagers invites viewers to connect with the story of privatisation from the perspective of the zaballeen. It does this by switching between stories of sibling rivalry to monologues reflecting on their hopes for the future, their successes and setbacks. We gain a real sense of the importance of the Recycling School as a tool to educate young people and build community cohesion. We can feel engaged in the strategies used by the zaballeen to reclaim their share of the garbage market during their community meetings.

What’s missing?

But the story leaves a lot unsaid.

It does not tell of the illegal status under Egyptian law of the zaballeen’s recycling activities. It does not mention that in addition to pushing them out of the waste management sector, the municipality also culls the zaballeen’s other source of income – pigs – due to the swine flu epidemic. We do not see any female zaballeen, nor do we hear that, after the privatisation of waste management, many zaballeen women ended up working in factories. There is a prominent female character, but she already has a job, as a social worker/community advocate within the zaballeen community.

When the Recycling School chooses Adham and Nabil to go to Wales as part of a sponsored trip to learn about recycling in other countries, the viewer is left with so many questions. Who sponsored the trip? Why Wales when the zaballeen recycle 80% of what they collect and the Welsh recycling representative says Wales only recycles 28%? In what way were the zaballeen expected to use the new technologies they were being exposed to when the local authorities did not even recognise their work?

We do not hear from the private waste management officials their perspectives on the state of waste management in Cairo, or why they decided to invest in the city. And we only get a glimpse of the perspective of a municipal official who explains to the zaballeen that working on a landfill is not safe. If you know a lot about the zaballeen in Cairo, your knowledge will help you to fill in the gaps.

But, watch it!

I hope that all of the things I have pointed out does not detract from the fact that the film is an excellent one. In fact, it may have been deliberate on the part of the director to leave out the details I mentioned, because she wants the viewer to go beyond the film and find out more about the zaballeen. The viewer will find that life for the zaballeen has changed since the 2009 release of this multiple award winning documentary. So, go watch it! (More information here).