Having commenced my career as an apprentice joiner way back in 1986, I had always appreciated the historic built environment. During the long career that followed I was fortunate to work predominantly on historic buildings, manufacturing bespoke joinery products such as Georgian and Victorian shopfronts, period doors and entrances, boxframe windows and shutters, geometric timber staircases, and an eclectic mix of traditional period fitments for both domestic and commercial historic properties.

Despite having progressed to management, and having established my own successful manufacturing business, a passion for architectural design led me to change direction following the completion of a building surveying course. This was the first step towards becoming a Chartered Architectural Technologist and towards undertaking a qualification in Architectural Conservation. The MSc Architectural Conservation course at the University of Kent had appealed to me previously, as its flexible part time option would have allowed me to maintain my design and consultancy work. However, finding the right time to commit to two year part time study was constantly frustrated by work and personal commitments.

The 2020 Covid-19 Pandemic impacted hard on my business which resulted in an immediate downturn and left a void that would have been difficult to fill in the uncertain times that followed. Therefore, I took the decision to turn the negative into a positive and reverse the plan I had been considering by undertaking work on an enforced part time basis and to embark on study full time. This has turned out to be the best decision I have made throughout my long career and has already opened up doors to a new career path which compliments my existing skillset, and which will provide the practical experience to consolidate the theoretical knowledge the course provided.

Although I was confident in my abilities I had not undertaken academic studies for several years and this had been one of the hesitations that had prevented me taking the plunge previously. Having now completed the full time course I realise that these hesitations should not have been a barrier as the lecturers were understanding, supportive, extremely knowledgeable, and managed to push you out of your comfort zone to achieve results and realise potential. This said, the course is extremely comprehensive and demands a large degree of self-discipline and dedication to complete the four modules and dissertation successfully. However, the hard work is worth it as it is an extremely interesting and knowledgeable course which is accredited by the IHBC as meeting all recognised competences.

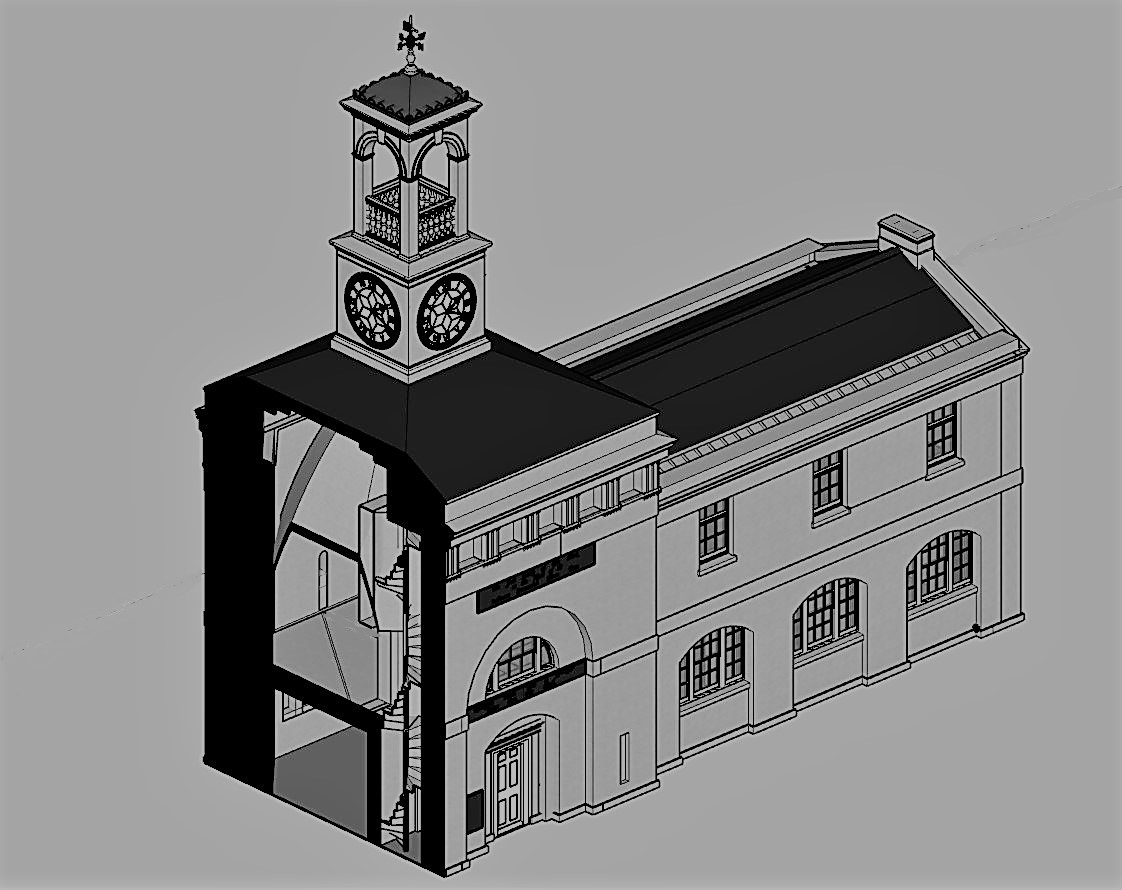

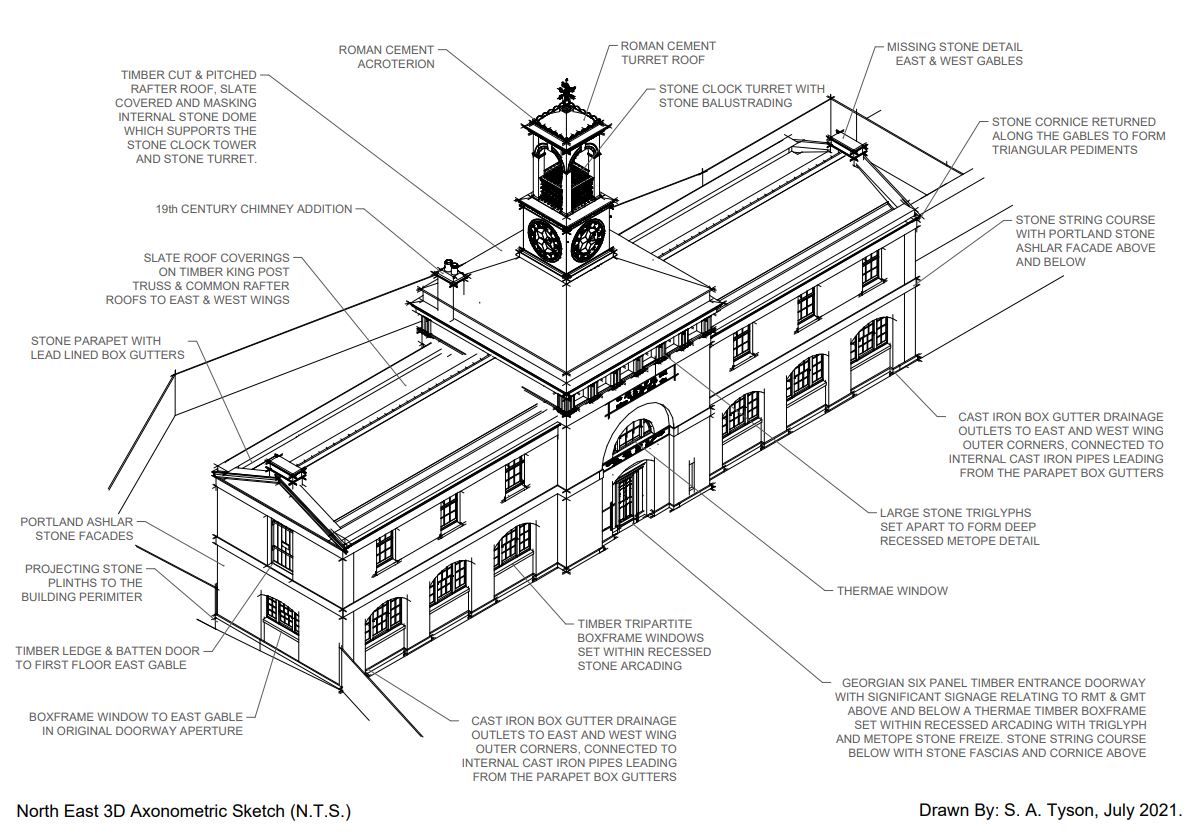

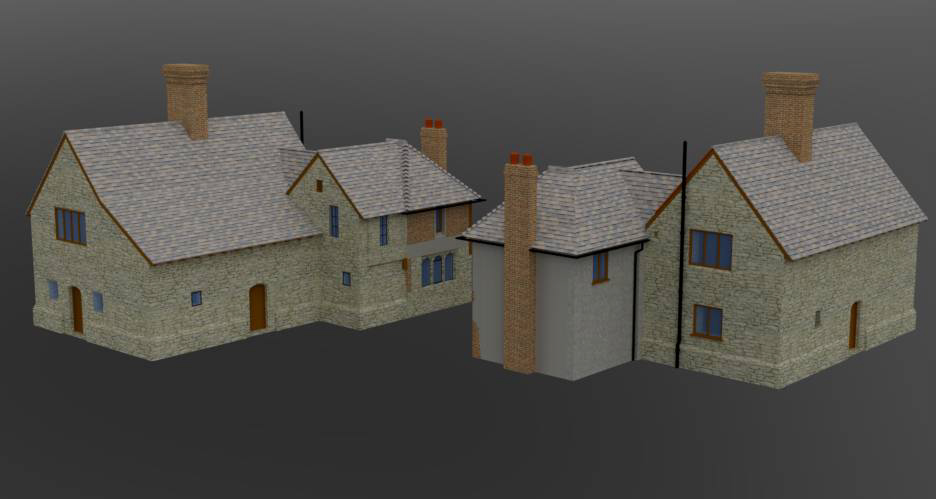

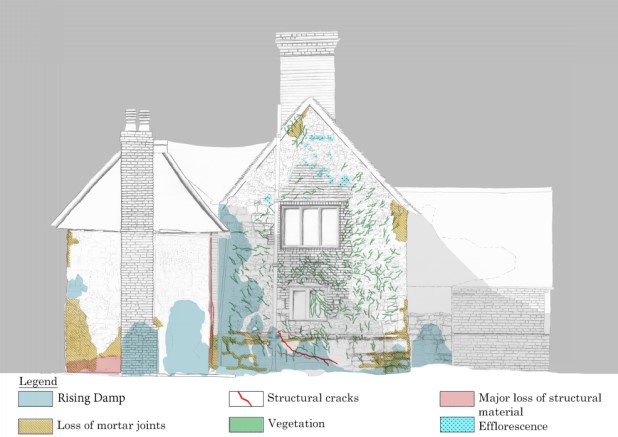

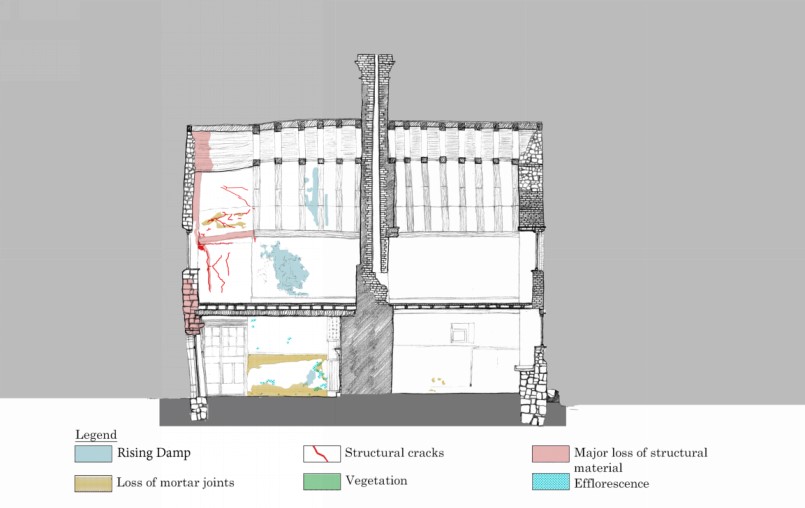

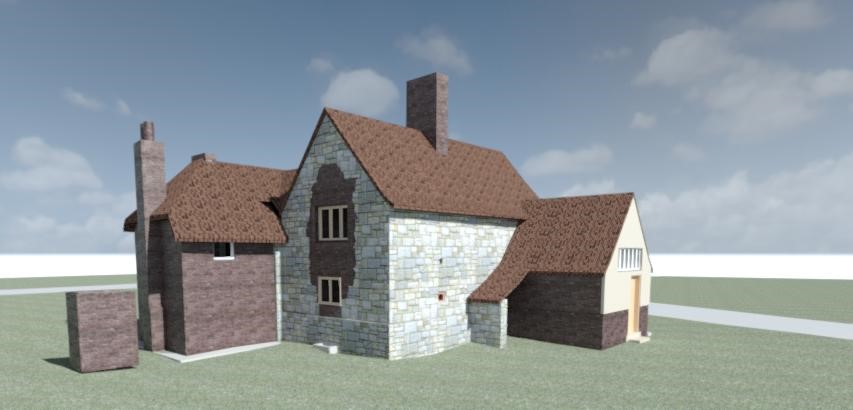

Modules on Heritage Legislation, Conservation Principles, Intervention, and Structural Appraisal provide a holistic understanding of architectural conservation which provided the theoretical knowledge to undertake the end of year dissertation. Having completed modules on the conservation areas of Herne Bay, Somerset House, Northgate, and St Andrew’s Chapel Boxley, I chose the Neo-Classical Clock House building at Ramsgate as my case study building for the dissertation. This proved to be an extremely enjoyable project, especially as I was encouraged to undertake a combination of a theoretical topic and a design proposal. The project used the Clock House building as it is currently on Historic England’s Heritage at Risk register and is in an area facing socioeconomic challenges. This provided an opportunity to analyse the effective use of Conservation Management Plans as well as developing the skills learnt through the course. This included historical research, how the building was designed and its development, site surveys and documentation, identifying levels of significance and mapping the buildings condition, preparing a statement of significance and discussing policies and strategies that would prevent further harm occurring and promote its significance and viable use to attract investors.

I would thoroughly recommend this course to anyone interested in architectural conservation or those who have an appreciation of the architectural form found within the historic built environment. It is a demanding course but the enjoyment offsets the hard work required, and I am sure you will not regret the decision to enrol!

Steven Tyson, 2021