This review of Comedy and Mental Health: Future Directions was published originally on www.thepolyphony.org

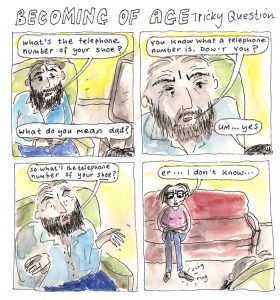

Image credit: Nicola Streeten (Twitter: @NicolaStreeten, Instagram: nicolast.reeten)

Does comedy, from stand-up to sitcoms, offer interesting insights into experiences of mental health? Could comedy even outline strategies to cope with certain mental health challenges? These and other questions were the focus of Comedy and Mental Health: Future Directions, which took place on 1 May 2019 and was organised by the Theatre and Performance Research Cluster and the Identities, Politics and the Arts Research Cluster in the School of Arts at the University of Kent. The organizers were Dr Dieter Declercq and Dr Oliver Double. At the symposium, eight speakers from a variety of academic and professional backgrounds delivered short presentations on what they consider the most pressing questions and challenges for future research on mental health and comedy, especially stand-up comedy. The event was designed to stimulate further research into comedy and mental health by identifying new research topics, exchanging methodological strategies and exploring interdisciplinary and collaborative research.

This symposium responded to the growing prominence of mental health as a topic in the comedy industries. Stand-up comedians like Susan Calman, Ruby Wax, Felicity Ward and Hannah Gadsby have all incorporated experiences of mental illness in their performances, often supplemented by activism to promote mental health awareness. In 2017, the Edinburgh Fringe Festival acknowledged this development by introducing an award for the best stand-up comedy show about mental health, in partnership with the Mental Health Foundation. Further, organisations like The Comedy Trust in Britain and Stand Up For Mental Health across North America have been developing stand-up comedy workshops to foster mental wellbeing since the mid-2000s. This attention to mental health is not just limited to stand-up comedy. TV comedies like Fleabag, BoJack Horseman and Crazy Ex-Girlfriend have similarly been praised for dealing with the topic.

There is also an existing (and rather vast) scholarly literature around humour and mental health. Yet, scholarship has not yet fully responded to this growing attention to mental health in the comedy industry. In this respect, there is a significant difference between humour in an everyday context and comedy in an artistic context – and the bulk of the available research has focused on the former, not the latter. For example, one particularly seminal methodology is the Humor Styles Questionnaire, introduced by Martin and colleagues (2003), and since used ‘in over 125 published studies’ (Martin and Kuiper 2016, 504). Crucially, according to Martin, ‘[s]pending a lot of time laughing at sit-coms on TV is likely to make you less healthy, rather than more healthy! In my view, if there really are any emotional or physical health benefits of humor, they’re more likely to come from conversational humor’ (Martin and Kuiper 2016). This statement certainly demands critical investigation, especially given the growing exploration of mental health in the comedy industries.

Comedy and Mental Health: Future Directions was designed as a conversation starter around the study of comedy and mental health. Speakers were invited to reflect on future directions, rather than present on completed research projects. Hence, this review will focus on outlining some directions for future research that arose from discussions on the day. These future directions are eclectic. As stressed in talks throughout the day, comedy is complex. For one, there is not one kind of comedy, but a range of comic expression across genres and media. Moreover, comedy can be approached from multiple angles, including the perspective of the performer, audience or promotor. Therefore, it is unlikely that future research will produce one overall approach to comedy and mental health. Instead, future research will likely consist of piecemeal projects that are attuned to specific complexities of comedy and mental health in a particular context. I therefore outline five future directions, which do not constitute a coherent research agenda, but highlight some interesting avenues for further investigation.

- To fully understand comedy and mental health, research should be collaborative including academics, public, private and third sector personnel, mental health service users, creative industry practitioners and other interested stakeholders. To some extent, Comedy and Mental Health: Future Directions was designed to stimulate such interdisciplinary and interprofessional exchanges. All speakers were active in Comedy Studies, but came from a variety of academic and professional backgrounds, including Dr Dieter Declercq (Film and Media Studies, Philosophy of Art), Dr Matt Hargrave, Prof Mary Luckhurst and Dr Shaun May (Drama and Performance Studies), Dr Sharon Lockyer (Sociology, Communication Studies), Dr Nicola Streeten (Comics Studies, graphic artist), Lynne Parker (CEO Funny Women) and Cait Hogan (stand-up comedian). It was certainly valuable to approach the topic of comedy and mental health from such a variety of perspectives. Still, it would be great if future events like these could also aim to include participants with backgrounds in Medicine, Health Care and Psychology. Such interdisciplinary and interprofessional events are not always easy to set up, but there was a strong sense that they are needed to achieve real progress in the field.

- Delegates who are themselves practitioners highlighted the usefulness of combining practical and theoretical approaches at future events and in future research projects. They specifically suggested that future events and research could incorporate practical comedy exercises from a range of media, including stand-up comedy and graphic art. In this respect, there are several professional organizations who offer comedy courses around mental health. It would no doubt be interesting for researchers to familiarise themselves with exercises from such workshops. Perhaps the only barrier to such integration of practical approaches in academic research is financial, because it requires some amount of funding to appropriately remunerate the practitioners.

- Another avenue suggested by practitioners was to investigate the effect of audience reactions on the comedian’s sense of self and wellbeing. Of course, in every context, social interactions are very significant to our mental health and wellbeing. As far as comedy is concerned, perhaps the most fruitful genre of comedy to study in relation to audience interaction is stand-up comedy, which is foremost an interactive art form. A stand-up comedy performance is always to some extent a product of the interaction between comedians and their audience. Such interaction could be studied in live performances and recordings, but also sometimes in written materials of audiences which form part of stand-up comedy performances. Interaction between stand-up comedians and audiences also often continues off state, for example through personal correspondence. In this respect, the British Stand-up Comedy Archive at the University of Kent has a large collection of such recordings, correspondence and other ephemera.

- Participants agreed that future research should be aware of how people’s engagement with comedy of is informed by intersections of identity, including gender, race, sexuality, social class, age and disability. I will give two examples that were discussed in talks. First, existing prejudices, like the mistaken idea that autism is incompatible with humour, may act as a barrier to fully understand the multifaceted role of comedy in the autism community, including how it may contribute to good mental health. Second, future research should map out existing barriers in the access of comedy festivals, performances and workshops for certain demographics. For example, people with certain disabilities or financial problems, which can go hand-in-hand, may be significantly impaired from accessing comedy in certain contexts.

- The final direction for future research goes to the very heart of the interaction between comedy and mental health. Delegates identified it as the ‘Nanette Conundrum’. In Hannah Gadsby’s stand-up special Nanette, she argues that stand-up is incapable of dealing with certain traumatic life experiences; and yet she produced it at a time when personal trauma was becoming an almost ubiquitous element in Edinburgh shows (e.g. rise of the ‘dead dad’ show, etc.). How can we reconcile this paradox? The answer requires a better understanding of the specific aspects of comedy that contribute or detract from good mental health. Such understanding would be sustained by research that is interdisciplinary, interprofessional and attuned to the complexities of comedy. Hopefully, Comedy and Mental Health: Future Directions is a useful step in that direction. Readers who want to join the conversation are very welcome to leave a message here or at https://thepolyphony.org/2019/05/29/comedy-and-mental-health-future-directions-conference-review/

Bibliography

Kuiper, Nicholas A., and Rod A. Martin. 2016. “Three Decades Investigating Humor and Laughter: An Interview With Professor Rod Martin.” Europe’s Journal of Psychology 12(3): 498-512.

Martin, Rod. A., Patricia Puhlik-Doris, Gwen Larsen, Jeanette Gray, Kelly Weir. 2003. “Individual Differences in Uses of Humor and their Relation to Psychological Well-Being: Development of the Humor Styles Questionnaire.” Journal of Research in Personality 37(1): 48-75.