Rohingya Muslims are labelled as the world’s most persecuted minority group, and have received considerable media coverage throughout the world (1–3). This blog post examines the conflict in Myanmar and the intractable nature of the conflict by using Paul Wehr’s conflict map, providing a quick macro perspective of the conflict at a certain moment in the conflict. Since the conflict in Myanmar has various significant actors and parallel conflicts between the actors, this essay will primarily concentrate on the conflict involving the Rohingya ethnic group. Wehr provides a useful framework to break down a complex conflict and analyse the actors, relationships, and issues, which are depicted in a conflict map. Furthermore, the conflict history, context, and dynamics are also included in the macro analysis of a conflict and qualitatively analyses the relationships between the actors, agency and the structures (4).

Myanmar is one of the longest running conflicts, with the roots of ethnic tensions going back generations. During the Mrauk-U dynasty (1430-1785) the Rohingya lived peacefully together with the Buddhist Arakenese and Burmese. However, in 1785 Buddhist Burmese invaded Arakan, also known as Myanmar’s western state of Rakhine, and executed or drove out the Muslim Rohingya ethnic group into Bengal, which was then in the British Raj in India. During the first Anglo-Burmese War from 1824 to 1826, the British took control of Arakan and incentivized Bengali farmers to move back to Arakan. This high influx of migrants from British India created ethnic tension with the mostly Buddhist Rakhine in the area, which is still felt today (5). Due to this history, many Rakhine dispute the claim that Rohingya have a distinct ethnic heritage and historic association to the Rakhine State, because the Rakhine view the Rohingya as ‘Bengali’ and therefore they do not have religious, cultural or social ties to Myanmar and the state of Arakan (6).

Myanmar has been torn by civil war and ethnic conflict ever since it regained independence from British rule in 1948 (7). After achieving independence, Myanmar became a republic and adopted the parliamentary democracy system (8). During the British rule the ‘divide and rule’ policy was put in place and divided Burma into two parts: Burma Proper and the periphery. However, after the British rule, local leaders came into power and ruled the states, this shift is said to have increased ethnic awareness in Burma (9). From 1962 until 2011, the military government ruled the country and abolished the democratic government. The military government attempted to inforce a homogenous nation, which was exemplified in the discriminatory national policies and the harsh military rule. Thus, this military rule created an environment of distrust (10,11). Since then rebel armed groups fought to attain rights and freedoms and in the hope of changing the structure of Myanmar.

In 2011, the military rule ended and the government underwent a significant transformation. The government became more democratic through the freeing of political prisoners, showing a greater openness towards public opinion, passing a law allowing peaceful demonstrations and improving US relations (12). In March 2016 a reform occurred transferring power to a ‘Civilian Government’. However, today the military still retains 25 per cent of the seats in Parliament. Despite the democratic reforms that former President Thein Sein enforced, the Burmese society remains dissatisfied. Unequal distribution of power, mostly held by former military leaders, persecution, violence and ethnic discrimination are still common in Myanmar. Although, Myanmar is becoming more democratic and wanting national reconciliation it is still filled with ethnic conflict (13).

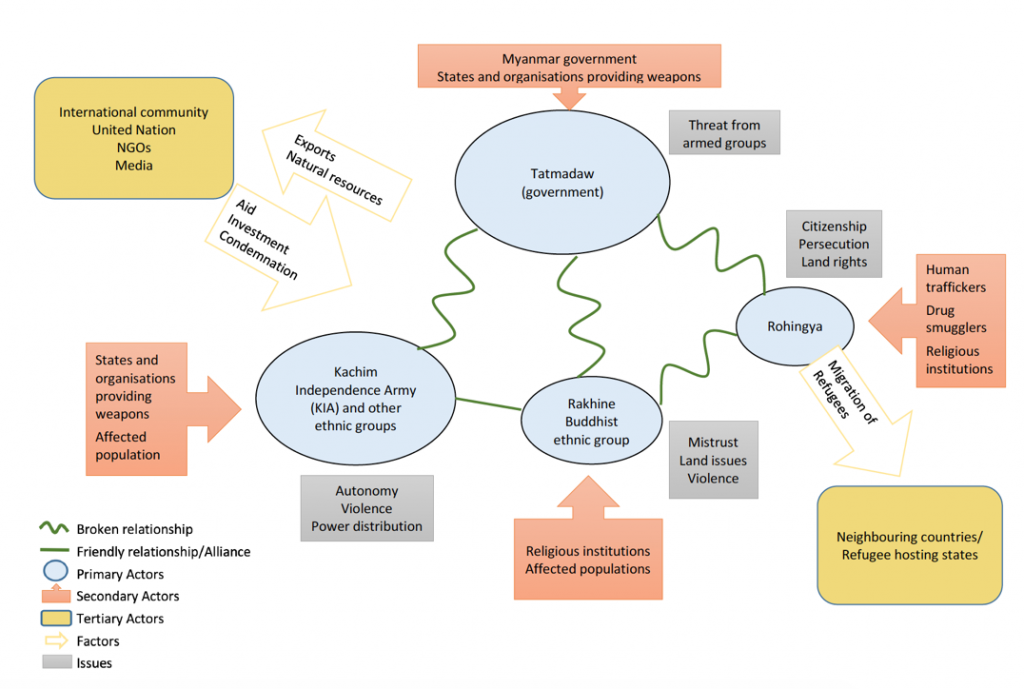

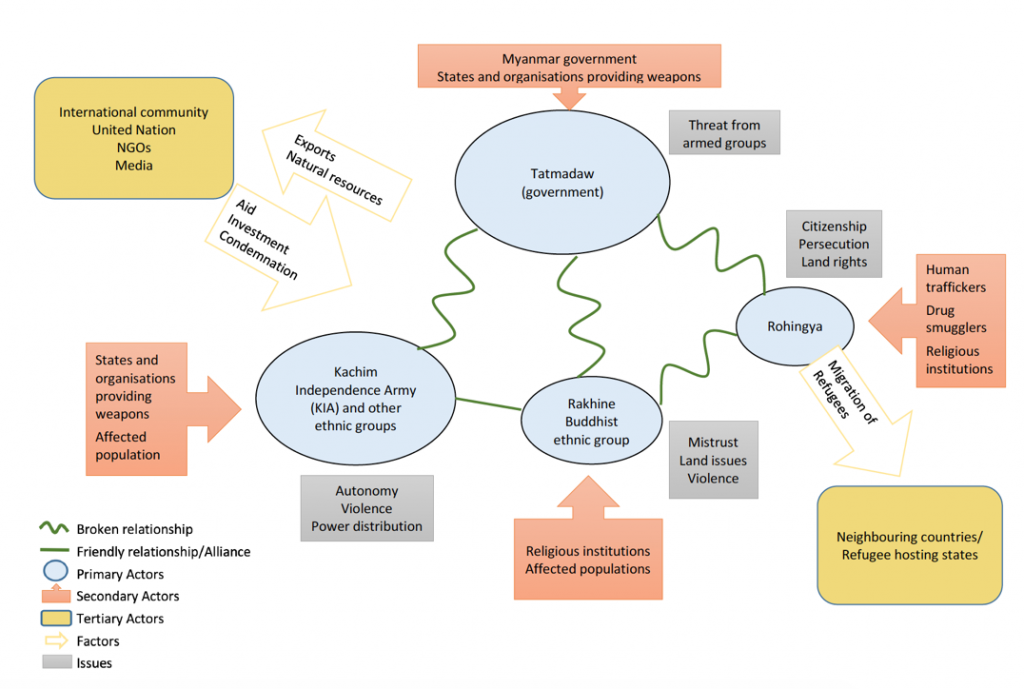

In order to examine the conflict actors three categories of actors are identified: primary actors, secondary actors, and tertiary actors. As can be seen in the conflict map the primary actors that are identified are Tatmadaw, the government, Kachin Independence Army (KIA) and two ethnic groups: the Rakhine Buddhists and Rohingya . The ethno-political conflict in Myanmar has been caused by the lack of recognition of ethnic groups. Myanmar is largely comprised of non-Burman minorities, who believe that they do not have sufficient rights, freedom and access to power (14). This conflict is rooted in the fundamental incompatibility of identities of the various ethnic groups in Myanmar. The Rohingya ethnic group represent only one puzzle piece in the ethno-political conflict in Myanmar.

When analysis the primary actors of this conflict, it can be seen that the conflict actors are mostly individual ethnic groups in Myanmar, since the conflict is of an internal nature. Some of the recent clashes are occurring between the Tatmadaw armed forces and the rebel groups present in the Kachin state. One of the major ethnic rebel groups are the KIA that operate for the Kachin Independence Organisation. The KIA want autonomy and a different power distribution that exists now, which has resulted in violent altercations (5).

The Arakan state is populated by Rakhine Buddhist as well as Rohingya. As can be seen from the history, the Rakhine and Rohingya have a standing history of mistrust and still remain in conflict about land rights issues, which has resulted in ongoing violent altercations. The Rohingya people, who do not have citizenship rights from Myanmar or Bangladesh, are being persecuted by the Myanmar government and are in violent conflict with the Rakhine (5). Thus, many Rohingya have fled due to being deprived of civil, economic, political and cultural rights. Normally, refugees are under the protection of the international refugee laws and human rights laws, however, since the Rohingya are suppressed by the government this is not applicable (15). In order to protest the mistreatment of the Rohingya, and in order to gain citizenship, the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army is fighting against the Tatmadaw. Furthermore, the intensity of persecution has increased against the Rohingya minority since 2011. This persecution has two fronts: the Rohingya minority are in conflict with both the Tatmadaw and the Rakhine Buddhist population (13).

Secondary actors, actors that have an indirect stake in the outcome of the conflict, include the affected population, states and organisations providing weapons, drug smugglers, human traffickers, the Myanmar government, and religious institutions. Due to the persecution of the Rohingya, they are vulnerable to human traffickers and drug smugglers. Furthermore, different religious institutions have backed the Rohingya and Rakhine Buddhist, which has added fuel to the violence of the conflict (17).

Tertiary actors, who can act a mediators or peacekeepers, also have a stake in the conflict in Myanmar. The international community, for example the United Nations, have become involved as mediators, have tried to negotiate peace and provide aid. However, with the involvement in Myanmar, the international community also verbalises condemnation. The UN is active in Myanmar and has worked together with the Myanmar government and ethnic groups to strengthen their democracy, human rights and reconciliation process, provide humanitarian assistance and build a national identity for the whole population of Myanmar (18).

In addition, other countries, such as China, also act as tertiary actors due to their investments in Myanmar and thus want to protect their investments (19). Furthermore, neighbouring countries such as Bangladesh, China and Thailand have tried to facilitate reconciliation with the Rohingya in Myanmar, because of the influx of refugees they have received and the problems that arise due to this. According to the UN, Bangladesh has received the most Rohingya refugees amounting to 530,000 Rohingya (20,21).

Media has also added pressure on the government and has raised international awareness about the stateless Rohingya ethnic group. Since many sanctions have been lifted, the Myanmar government is trying to strengthen the economy and participate in the international market through exports (22). Maintaining and improving its stance internationally is of great interest in order to improve its economy and become less reliant on Chinese investments. Thus, the government is incentivised to reconcile and build peace. In addition, through the media the Rohingya ethnic group has received recognition and legitimacy for their cause to fight for citizenship and land rights (19).

As can be seen from the conflict map illustrated above, the Myanmar conflict is a complex, multi-dimensional issue with different actors, and a variety of objectives. Through the use of Paul Wehr’s conflict map, the complexity of the conflict becomes easier to comprehend and the conflict actors and their relationship become visible. However, Wehr’s conflict map provides only an overview of the conflict and does not provide a comprehensive and in-depth analysis.

This moment in time represents a ripeness in the conflict history. The government and the ethnic groups of Myanmar are ready for change and know that the ethnic struggles cannot remain and have to be addressed and mediated (23). Currently, Nobel Peace Laureate and President Aung San Suu Kyi has given Myanmar hope to becoming more democratic and regaining more freedom. However, the voters and the international community have expressed critiques because acute social, economic and political problems still remain. Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy (NLD) put through ceasefires, which stopped the initial fighting between the government and ethnic armed groups. However, in order to reach peace, conflict reconciliation has to occur on all levels and between the various ethnic minorities, because without reconciliation between the primary actors ceasefires will only be temporary (24). The NLD is working towards the promised reforms, such as negotiating a nationwide peace agreement with the various ethnic armed groups, however, the NLD government refuses to address the conflict with the Rohingya. The conflict with the Rohingya ethnic group has to be officially addressed by the government and reconciliation needs to occur between the Rohingya and Rakhine in order to establish peace.

By Marie Hoffmann

- Amnesty International. Who are the Rohingya and what is happenign in Myanmar? [Internet]. 2017. Available from: https://www.amnesty.org.au/who-are-the-rohingya-refugees/

- The Economist. The most persecuted people on Earth? [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2017 Oct 20]. Available from: https://www.economist.com/news/asia/21654124-myanmars-muslim-minority-have-been-attacked-impunity-stripped-vote-and-driven

- Broomfield M. UN calls on Burma’s Aung San Suu Kyi to halt “ethnic cleansing” of Rohingya Muslims [Internet]. The Independent. 2016 [cited 2017 Oct 19]. Available from: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/asia/burma-rohingya-myanmar-muslims-united-nations-calls-on-suu-kyi-a7465036.html

- Wehr P. Conflict Regulation. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press; 1979. 245 p.

- Yasmin K. Rohingya s ’ Debate and 1951 International Refugee Convention : A Security Concerns Analysis. J Altern Perspect Soc Sci. 2017;8(4):401–23.

- United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner. Report of OHCHR mission to Bangladesh: Interviews with Rohingya fleeing from Myanmar since 9 October 2016 [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2017 Oct 18]. Available from: http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Countries/MM/FlashReport3Feb2017.pdf

- Silverstein J. Burma’s Struggle for Democracy: The Army Against the People. In: May RJ, Selochan V, editors. The Military and Democracy in Asia and the Pacific. ANU E Press; 2004. p. 69–87.

- Neher CD. ASIAN STYLE DEMOCRACY. Asian Surv [Internet]. 1994;34(11):949–61. Available from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/2645346.pdf

- Burma Centrum Nederland. The Kachin Crisis : Peace Must Prevail. 2013;(Burma Policy Briefing Nr. 10):1–20.

- Walton MJ. The “Wages of Burman-ness”: Ethnicity and Burman Privilege in Contemporary Myanmar. J Contemp Asia [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2017 Oct 18];43(1). Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/00472336.2012.730892?needAccess=true

- Hliang KY. Burma: Civil Society Skirting Regime Rules. In: Alagappa M, editor. Civil Society and Political Change in Asia [Internet]. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press; 2004 [cited 2017 Oct 20]. p. 389–418. Available from: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=fqNsVB0hJRYC&pg=PA389&lpg=PA389&dq=civil+society+skirting+regime+rules&source=bl&ots=tAxNTOC-YP&sig=nVINvBipfwJab6jUVyFe2OV9E7w&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwim3Me5i__WAhXiIMAKHYsSBEQQ6AEIKjAB#v=onepage&q=civil society skir

- BBC News. Timeline: Reforms in Myanmar [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2018 Jan 29]. Available from: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-16546688

- United Nations General Assembly. Situation of human rights of Rohingya Muslims and other minorities in Myanmar: Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. 2016 [cited 2017 Oct 18]; Available from: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G16/135/41/PDF/G1613541.pdf?OpenElement

- Beech H. The Face of Buddhist Terror. TIME [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2017 Oct 19]; Available from: http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,2146000,00.html

- Imran FH Al, Mian N. The Rohingya Refugees in Bangladesh: A Vulnerable Group in Law and Policy. J Stud Soc Sci. 2014;8(2):226–53.

- Albert E. The Rohingya Crisis [Internet]. Council on Foreign Relations. 2018 [cited 2018 Jan 30]. Available from: https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/rohingya-crisis

- South A. Prospects for Peace in Myanmar: Opportunities and Threats [Internet]. PRIO Paper. 2012 [cited 2017 Oct 19]. Available from: https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/157179/South-Prospects-for-Peace-in-Myanmar-PRIO-Paper-2012.pdf

- United Nations. United Nations in Myanmar [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2017 Oct 19]. Available from: http://mm.one.un.org/

- Petrie C, South A. Mapping of Myanmar Peacebuilding Civil Society [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2017 Oct 19]. Available from: http://www.eplo.org/civil-society-dialogue-network.html

- Win A. United Nations Information Centre Yangon [Internet]. United Nations Information Centre Yangon. 2017 [cited 2017 Oct 19]. Available from: http://yangon.sites.unicnetwork.org/2017/10/19/statement-by-adama-dieng-united-nations-special-adviser-on-the-prevention-of-genocide-and-ivan-simonovic-united-nations-special-adviser-on-the-responsibility-to-protect-on-the-situation-in-northern/

- Asrar S. Rohingya crisis explained in maps [Internet]. Al Jazeera. 2017 [cited 2017 Oct 18]. Available from: http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/interactive/2017/09/rohingya-crisis-explained-maps-170910140906580.html

- CSS. Myanmar: Limited Reforms, Continued Military Dominance. [Internet]. CSS Analysis in Security Policy. Zurich; 2012 [cited 2017 Oct 18]. Available from: https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/144269/CSS-Analysis_115.pdf

- Zartman W. The timing of peace initiatives: Hurting stalemates and ripe moments. Glob Rev Ethnopolitics [Internet]. 2001 Sep [cited 2017 Oct 20];1(1):8–18. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14718800108405087

- Selth A. Aung San Suu Kyi and the Tatmadaw [Internet]. Stratfor Worldview. 2017 [cited 2017 Oct 20]. Available from: https://worldview.stratfor.com/article/aung-san-suu-kyi-and-tatmadaw