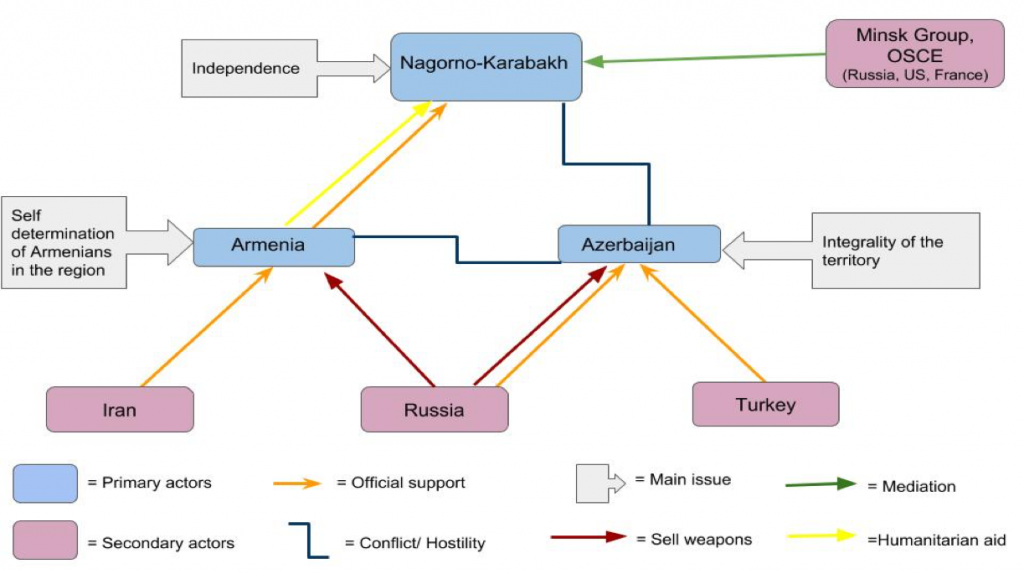

This article seeks to identify the leading causes and the dynamics of the conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh (Figure 1). The analysis includes the various actors engaged in the dispute and divides these actors in two main categories based on their degree of involvement.

Historical background

The territorial claim over the Nagorno-Karabakh region has profound and deep roots. Between the 1918 and 1920, at the end of World War I, both Armenia and Azerbaijan gained their independence from the Russian Empire. The independence brought with it the disputed claim over the Nagorno-Karabakh territory which was formally in Azerbaijan’s borders but inhabited by Armenians (Väyrynen, 2008). In 1920, the Soviet Union encompassed the two countries, and possessed a significant part of their independence. The URSS established the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast (NKAO) in 1923, as part of the Soviet Republic of Azerbaijan. As in Miller’s words: “The conflict lay dormant but did not die”.

During the 1980s, the Gorbachev’s liberal policies weakened the control over the Caucasus, and as a consequence, many strikes and protests emerged in the region. Armenians from the Nagorno-Karabakh reclaimed their membership to Armenia, and thousand of Azerbaijanis left the region (Väyrynen, 2008). The conflict reached its peak in 1989 when thousand of people died in one of the most cruel battles in the Caucasus (Hensilki Commision report, 2017). The violence lasted until May 1994 when a cease-fire, the Bishkek Protocol, was signed by Armenia and Azerbaijan (Hensilki Commision report, 2017).

Underlying causes

A summary of the history explains only in part what caused this conflict. However, more factors should be taken into account to deeply understand the hostility in the region and the reason this hostility arose in all its violence.

Michael Brown clarifies that the circumstances fueling regional conflict may be classified into four levels: structural, political, economic, and cultural factors (Brown, 1996). In the analysis of Betts (Betts, 1999), the Nagorno-Karabakh case seems to be influenced by structural and cultural elements. At first, structural factors refer to the inability of the Azerbaijan government to oppose the rebellions and the geographical concentration in only one region of a specific ethnic group. The URSS’ policies encouraged the dependence on the central administration in its various republics. Consequently, the government of Azerbaijan, which officially controlled the Nagorno-Karabakh, was relatively ineffective and found it difficult to manage the Armenians who had their domicile in the region. Secondly, the cultural factors can be exemplified through the history of the Caucasus. Under the Ottoman Empire’s period of conquest, Armenians were persecuted by the Turkish in several occasions, the most notorious being the genocide of 1915. The events of that event remains very vivid in the Armenian collective memory and exasperate the contemporary antagonism over the Nagorno-Karabakh issue, because of the proximity of Turkish and Azerbaijani governments (Dadrian, 1995).

The collapse of the Soviet Union, the last dominant power in the region, was a major factor triggering the explosion of violence. Gurr and Katz bring to light the two main reasons why the breakdown of the URSS is essential to explain the conflict.

Ted Gurr talks of the rise of nationalist sentiment, guided by ethnic propaganda. The political atmosphere, created by Gorbachev’s policies of democratisation, paved the way for new demonstrations of previous hidden ethnic struggles. Gurr affirms that cultural identity becomes the basis for mobilisation when a group understands this identity as the origin of uneven allocation of economic or political resources or threatened by the current political system (Gurr, 1996). Armenians in Karabakh have realised such concerns were real, declaring economic and political discrimination by Azerbaijan. They used this sensed discrimination as a ‘manifesto’ to mobilise Armenians of the region (but also external support for the Armenian cause) against Azerbaijan.

As noticed by Mark Katz, there are different tactics used by dominant states to manage subordinate units. One of these tactics was used by the URSS: the “divide and rule” approach (Katz, 1996). When Stalin decided to give the Nagorno-Karabakh to Azerbaijan, he knew that in the region the majority of population was Armenian. The soviet leader exploited the struggle between subordinate groups in order to keep them from combining to question the central authority. For years, the central government used these strategies to maintain the control over the possessions, crystallizing and not solving conflicts.

Current Situation

The ceasefire in 1994 froze the conflict for the next 22 years. During this period the Minsk Group, a mediation board created by OSCE sought to find a peace agreement. The mediation team is composed by: Russia, United States and France. Are you trying to say that: the mediation team is composed by: Russia, United States and France. In this mediation team France acts as a representative of the European position in the conflict (OSCE website). The efforts have not produced valid results. This is because of two reasons: the interests of Russia that gains more from the current situation (Behlul, 2008) and the incapacity of the Group to overlap the strong positions maintained by Armenia and Azerbaijan (Mehtiyer, 2005). Furthermore, the ceasefire has been violated in different occasions. In particular, the attack in April 2016 was unexpected and violent due to the use of heavy artillery, that some experts argued that the conflict is no longer frozen (The Economist, 2016). Dissatisfaction caused by the stalled diplomacy and the fragility of the ceasefire may have driven Azerbaijan to change the current situation by other means (Broers, 2016) .

The question that remains is: why in 2016 and not before?

The answer can be explained in two parts. At first, the symmetry between the Azerbaijan and Armenia military forces are not valid anymore. Azerbaijan has invested an enormous amount of money to increase its military capabilities, ensuring a superiority on the battlefield respect the past (BBC, 2015). Furthermore, after more than 22 years without any appreciable result both sides mistrust the ongoing negotiation process (Garibov, 2015; Abbasov, 2015).

Actors involved

The actors involved in the conflict over the Nagorno-Karabakh region can be classified in two categories, primary and secondary actors. Armenia, Azerbaijan and Nagorno-Karabakh are considered part of the first category because of their direct involvement in the conflict. Russia is part of the secondary actors category because, even its policies can influence the sort of the conflict, there is no Russian military personnel on the battlefield. In addition, Turkey and Iran influence the resolution of the conflict because of their nearness and involvement in the history of both Armenia and Azerbaijan (Figure 2).

The government of Armenia during the early 1990s officially claimed the Nagorno-Karabakh region as part of its nation borders. Even this initial position, from 1998 the Armenian government has decided to support the independence of the region (Zurcher, 2007). The reclamation is based on the principle of self-determination of the Armenian population which inhabits the territory (Mustafayeva, 2016). A more in-depth interest could be gaining credibility on the international scene that always supported Azerbaijan on this issue. In the last 15 years, with the change in its leadership, Azerbaijan had troubles with the international community, especially EU, about human rights concerns. The Armenia government can use this dissatisfaction to find support for the cause (Fuller, 2013). Physical protection of the Armenians in the Nagorno-Karabakh is a priority for the government.

The Azerbaijani Government claimed the Nagorno-Karabakh as part of its territory. Their claim is also based on historical reason. They do not recognise the sense of belonging of the inhabitants of the zone because of the common origin of all population in Caucasus (Vayrynen, 1998). The only interest for the Azerbaijanis is the integrity of their territory, the Nagorno-Karabakh even poor of energetic resources represents the 30% of Azerbaijan (Hedenskow and Korkmaz,2016). It also represents a question of credibility and respect (Fuller, 2013).

The Nagorno-Karabakh wants the independence from Azerbaijan and the recognition of its republic by the international community (Merkedov, 2017). The formal independence will allow the Nagorno-Karabakh to be closer to Armenia, the country they have ever recognize as near to their culture (Harutyunyan, 2017). Nonetheless, the essential need to protect and keep the population safe remains. Despite the efforts to develop the government, the public opinion of the Nagorno-Karabakh is not taken into account or recognised in the negotiation process as well as in the international arena (Kopecek et co. 2016).

The official position of Moscow is supporting Azerbaijan’s claim. In reality, the Cremlino sells arms to both sides, and frequently feasible solutions were rejected inside Minsk Group because of Russian opposition (Hedenskog and Korkmaz, 2016; Mehdiyev, 2005). The real interest of Russia and the reason beyond its ambiguous relationships with both parties is the influence on the Caucasus. This influence is political as well as economical (CSS, 2013; Behlul, 2008). The energy corridor from the Caspian Sea to the EU is another incentive in addition to the vast market to sell arms (Lindenstrauss, 2015: Di Puppo, 2012).

Other secondary actors are the two neighbouring powers, Turkey and Iran.

The Turkish government officially support the Azerbaijan and its claim over the region of Nagorno-Karabakh (Markedonov, 2017).

There are many reasons beyond the position declared by President Erdogan. First of all, the past relationship and misunderstandings between Armenia and Turkey is considered a crucial reason to explain the Turkish consensus to Azerbaijan. The diplomatic relations between Armenia and Turkey that have been interrupted in 1993 because of the occupation of Azerbaijan districts by Armenian Armed Forces (Shirinov, 2017). Furthermore, the Government of Turkey always refused to recognize the genocide of Armenians in 1915, an important event in Armenian collective memory (Väyrynen, 2008). Secondly, an important factor that determines the Turkish approach to the conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh is the change in the Turkish foreign policy. Even Turkey and Azebarhian has a ethnic and religious kinship, Ankara always maintained a balanced position in the dispute over the Nagorno-Karabakh and supported a neutral profile, until seven years ago. The “Arab Spring” in 2011 has favoured a new nationalist fervor in Turkey, encouraging a sense of appartenance with the majority of muslims in Azerbaijan. President Erdogan used this phenomenon to preserve political legitimacy; he made the foreign policy more aggressive and supportive to Azerbaijan (Hedenskog and Korkmaz, 2016). At last but not at least, Turkey approves the revendication of Azerbaijan because of energy and economic issues. Ankara wants more control over the Caucasus and energy independence from Russia. If the government of Turkey will be involved in the resolution of the conflict, it will become a new centre of gravity for the region. (Fidan, 2010; Oskanian, 2011).

On the other hand, the other powerful neighbor, Iran, supports the position of Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh. The main reason of this choice lays on the hostility between Iran and Turkey over the control of muslims in the South Caucasus (Väyrynen, 2008). Another important element of the alignment is the national security of Iran. Many battles have been fought close to the border of Iran, compromising the safety of iranian population (Souleimanov and Ditrych, 2007).

Even the deep involvement of Turkey and Iran in the Nagorno-Karabakh issue, both countries have little wiggle room. Armenia cannot take advantages from the Iran support because of all the sanctions inflicted on Iran by the international community (Galstyan, 2013). Moreover, Turkey has little chance to participate in a potential conflict because of its obligations with international institutions, first of all, NATO (Fuller, 2013).

Conclusion

After almost 22 years of failed mediation efforts the frozen conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh has erupted again in 2016. The Minsk Group failed to understand the deep and vast causes of this conflict as well as the problematic participation of Russia in the mediation process. This powerful actor has many interests in the ongoing situation and gain more from the dispute than from its resolution. Furthermore, the powerful influence of Turkey and Iran does not allow smooth resolution of past hostilities.

However, the most complicated obstacle to resolving the conflict remains the strong claim of Azerbaijan over the region. Media and the international community do not pay much attention to this conflict and underestimate the instability that this conflict may bring into the Caucasus.

By Nancy Nicole Falco

(ed. Marie Hoffmann)

Work cited:

-Abbasov, N. “Minsk Group Mediation Process: Explaining the Failure of Peace Talks”, Journal of Caspian Affairs, Vol.1, No.2, Summer 2015, pp.59-76

-BBC (2015) “Nagorno-Karabakh conflict: Azeris dream of return”. From: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-30718551

– Behlul, A. (2008) “Who Gains from the “No War No Peace” Situation? A Critical Analysis of the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict”. Geopolitics, 13:572–599, 2008

-Betts, Wendy. 1999. “Third Party Mediation: An Obstacle to Peace in Nagorno Karabakh.” SAIS Review 19 (2): 161–183.

– Broers, L. (2016) “The Nagorny Karabakh Conflict Defaulting to War”. Chatham House

-CSS, Center for Security Studies (2013) “Nagorno-Karabakh: Obstacles to a Negotiated Settlement” No. 131, April 2013

-Brown, M.E., (1996) “International Dimensions of Internal Conflict”. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press

– Dadrian, V. N. (1995) “The History of the Armenian Genocide: Ethnic Conflict from the Balkans to Anatolia to the Caucasus”. Berghahn Books

– Di Puppo, L. (2012) “The Foreign Policy of Azerbaijan and Georgia”. Caucasus Analytical

– Fidan, H, (2010) “Turkish foreign policy towards Central Asia”. Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies, Volume 12, Number 1, March 2010

– Fuller, E. (2013) “Azerbaijan’s Foreign Policy and the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict”. Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI)

-Galstyan, N. (2013) The main dimensions of Armenia’s foreign and security policy. Norwegian Peacebuilding Research Centre

-Garibov, A. (2015) “OSCE and Conflict Resolution in the Post-Soviet Area: The Case of the Armenia-Azerbaijan Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict”. Caucasus International, Vol. 5, No: 2, Summer 2015

– Gurr, T “Minorities, Nationalists, and Ethnopolitical Conflict,” in Brown, M.E. (1996) “International Dimensions of Internal Conflict”. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press p. 53.

– Harutyunyan, A. (2017) “Two States Disputes and Outside Intervention: The Case of Nagorno-Karabakh conflict”. Eurasia Business and Economics Society, February 2017

– Hedenskog, J. and Korkmaz, K. (2016) “The Interests of Russia and Turkey in the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict”. Swedish Defence Research Agency

-Helsinki Commission Report (2017) From:https://www.csce.gov/sites/helsinkicommission.house.gov/files/Report%20-%20Nagorno-Karabakh%20-%20Design%20FINAL_0.pdf

– Katz, M. “Collapsed Empires,” in Chester Crocker, Fen Osler Hampson, and Patricia Aall, eds., “Managing Global Chaos” (Washington: United States Institute of Peace Press, 1996)

– Kopecek,V. , Hoch, T. and Baar V. (2016) “Conflict Transformation and Civil Society: The Case of Nagorno-Karabakh”. Europe-Asia Studies Vol. 68, No. 3, May 2016, 441–459

– Lindenstrauss, G. (2015) “Nagorno-Karabakh: The Frozen Conflict Awakens. Strategic Assessment” , Volume 18, No. 1, April 2015

– Markedonov, S. (2017) “The Nagorno-Karabakh: At the Crossroads of Foreign Policies”.

-Mehtiyev, E. (2005) “Armenia-Azerbaijan Prague Process: Road Map to Peace or Stalemate for Uncertainty?”. Conflict Studies Research Centre

-MIller, N. W. “Nagorno Karabakh: A War Without Peace” in Eichensehr, K. and Reisman, W.M. (2009) “Stopping Wars and Making Peace: Studies in International Intervention”. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers

-Mustafayeva, N. (2016) “Armenia’s recognition of Nagorno-Karabakh could trigger a war”.

-Shirinov, R.(2017) “Erdogan, Putin discuss Nagorno-Karabakh conflict”. Azernews, from: https://www.azernews.az/karabakh/122395.html

-OSCE, https://www.osce.org/mg/108305

– Oskanian, K. (2011) “Turkey’s global strategy: Turkey and the Caucasus”. IDEAS reports -Special reports, Kitchen, Nicholas (ed.) SR007. LSE IDEAS, London School of Economics and Political Science, London, UK.

-Souleimanov, E. (2016) “What the fighting in Karabakh means for Azerbaijan and Armenia”. CACI Analyst.

– Souleimanov, E. and Ditrych, O. (2007) “Iran And Azerbaijan: A Contested Neighborhood”. Middle East Policy Council, vol. 14

– The Economist (2016) “A frozen conflict explodes: After facing off for decades, Armenia and Azerbaijan start shooting”. From: https://www.economist.com/news/europe/21696563-after-facing-decades-armenia-and-azerbaijan-start-shooting-frozen-conflict-explodes

-Vayrynen, T. (1998) “New Conflicts and their Peaceful Resolution: Post-Cold War Conflicts, Alternative means for their Resolution and the Case of Nagorno-Karabakh”. The Aland Islands Peace Institute

-Zürcher, C. (2007).” The post-Soviet Wars: Rebellion, Ethnic Conflict, and Nationhood in the Caucasus”. New York: New York University Press.