by Kate Rennard (for BtS) and Jo Loosemore (‘Mayflower 400: Legend and Legacy’ exhibition curator at The Box, Plymouth)

What comes to mind when you think of Plymouth, England? For many people, it’s the port from which the Mayflower departed in 1620, on its way to North America. Since 1873, remembering this history has become a key part of Plymouth’s identity. Its tagline for many years was “the Spirit of Discovery,” there are Mayflower-named buildings and streets, and, not surprisingly, the city marked the Mayflower anniversaries in 1920 and 1970 with celebrations. Mayflower 400 in 2020 sought to commemorate the shared history through collaborations with Indigenous North American artists and activists for the first time. Whilst many events were curtailed by the pandemic, some projects did progress. Exhibitions opened and new possibilities arrived online too. However, in Plymouth, the story of the departure of the English colonists still matters. But perhaps there is now a greater understanding of arrival – on both sides of the Atlantic.

As a major port, Plymouth hosted many Indigenous North American travelers from the 1580s onward. For example, Epenow, a Wampanoag man from Martha’s Vineyard, was held captive in Plymouth for several years before the Mayflower set sail from there, contradicting popular beliefs about those colonists “discovering” New England.[1] He was also not the first or the last Indigenous North American to spend time in Plymouth. While some were only passing through the port on their way to somewhere else, others lived in the city for months or years. Building on earlier work by former Beyond the Spectacle research associate Jack Davy, we recently collaborated to chart these visits on a map. (PocketSights map: https://pocketsights.com/tours/tour/-Beyond-the-Spectacle%3A-Indigenous-Plymouth-2827). It shows Plymouth as a landscape traversed by many Indigenous peoples, who came as diplomats, soldiers, activists, performers, captives, and tourists. It amplifies their stories and commemorates their contributions to the port city over the course of 400 years.

In mapping these visits, we encountered some methodological issues, including problems of historical detail. Often the sources for earlier visits, such as newspaper articles, would give scant facts on locations, clearly enough for contemporary locals to recognize but not 21st-century readers. We know, for example, that the three Cherokee chieftains who arrived in 1762 went from “the landing place” in Plymouth to “the inn” where they “took the post to Plymouth.” However, their guide Henry Timberlake didn’t give any more information than that. Where did they land? What inn did they visit? Research revealed that in the late 1700s, there were two posting inns in the Plymouth area, the Prince George at Plymouth Dock and the King’s Arms, close to Sutton Harbour. We can’t be sure which of these they patronized but we chose to place the marker at the site of the long-demolished King’s Arms, since they would have travelled through that part of the city on the coach either way.

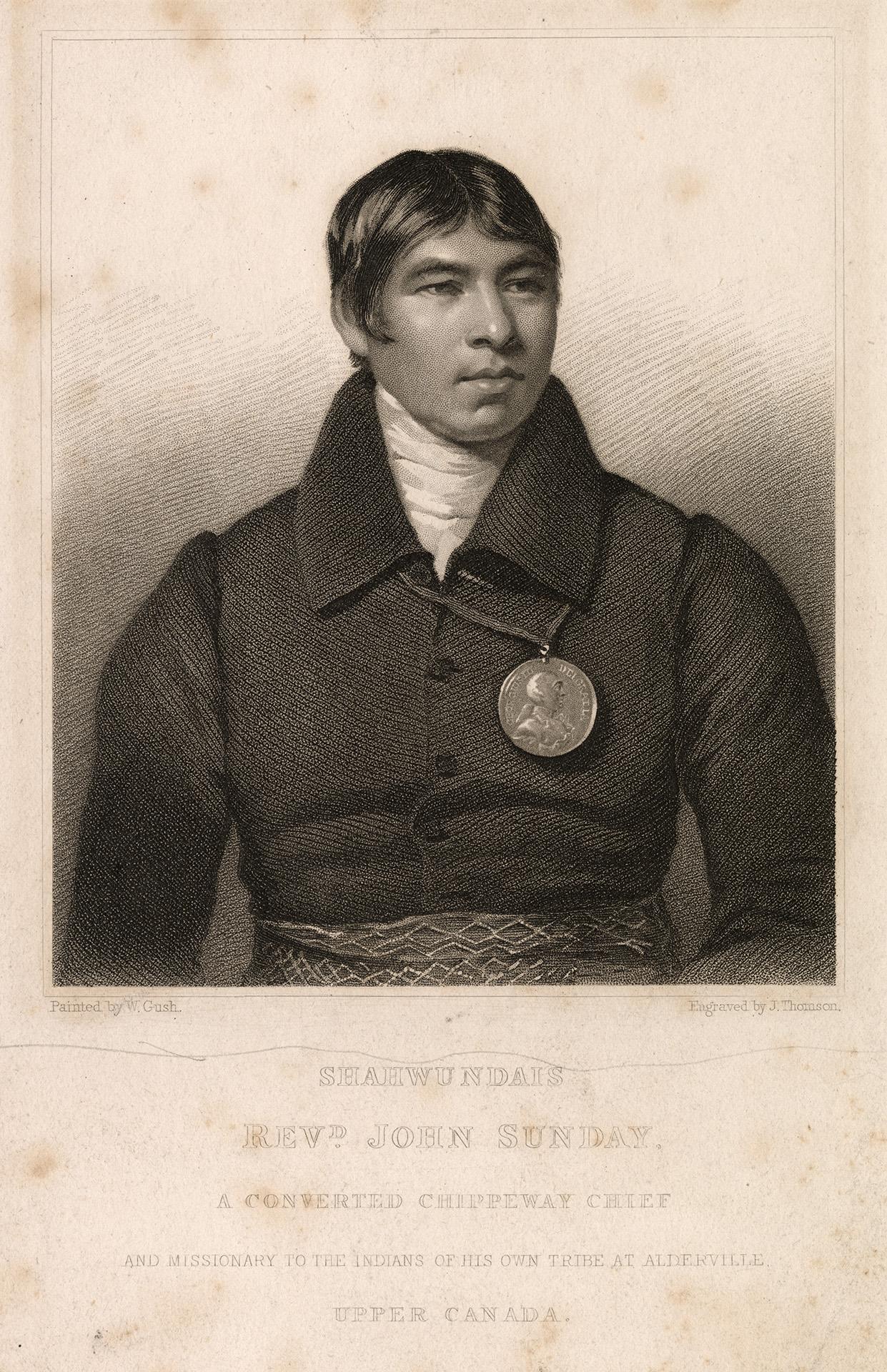

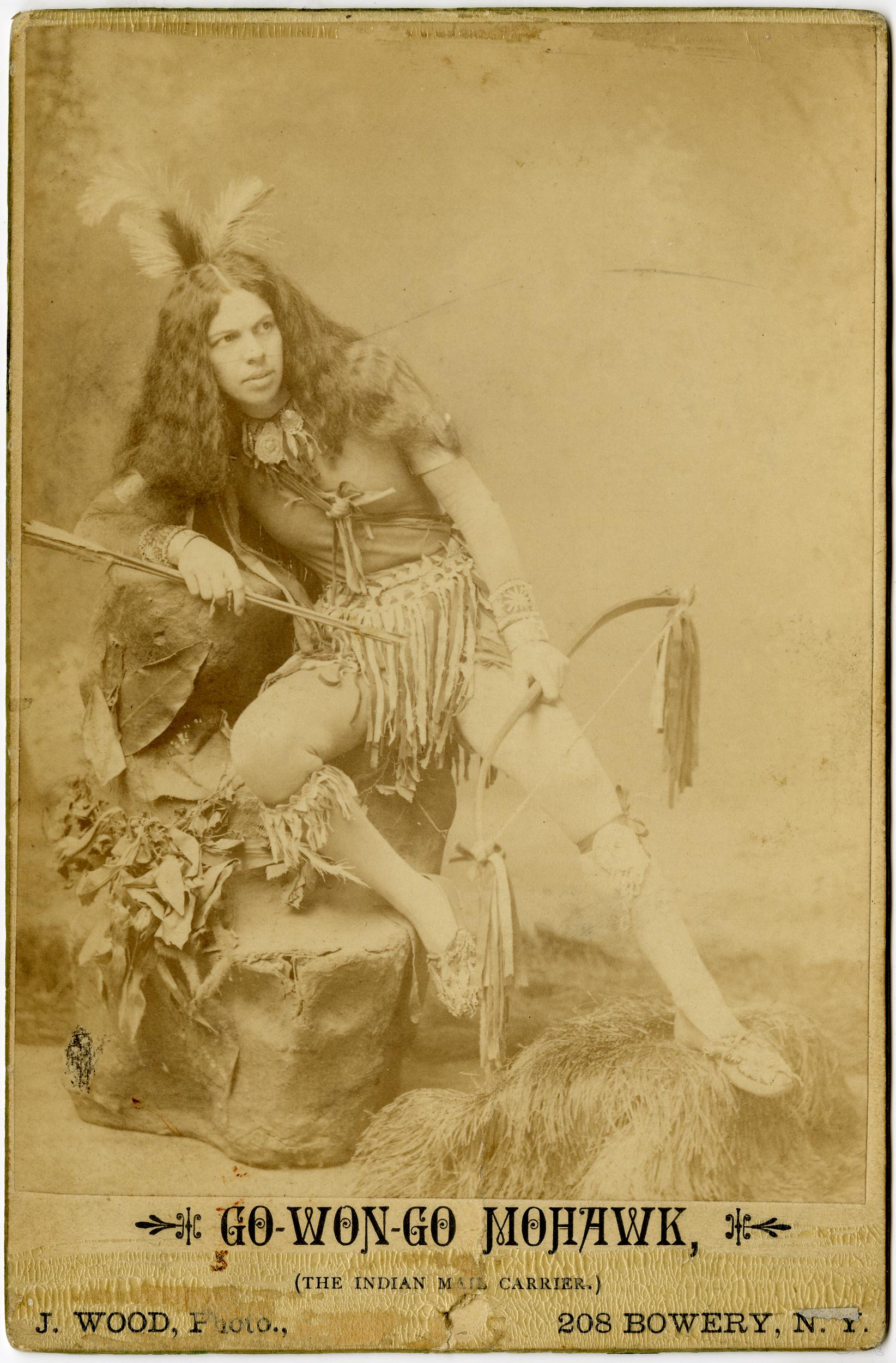

Timberlake’s larger description of the Cherokees’ arrival also demonstrates an important point about Indigenous presence in Plymouth. While people often think of Plymouth (and Britain) as a space “free of Indigenous bodies, minds, and histories,” the reality was very different and contemporary Plymothians were well aware of this presence because they were often an enthusiastic audience.[1] As Timberlake describes, the arrival of the three Cherokee chiefs in 1762 “drew a vast crowd of boats, filled with spectators, from all the ships in the harbor” and the landing place was also crowded. When John Sunday, a Mississauga Ojibwe chief and Methodist minister, preached at what is now Methodist Central Hall in 1837, “every part of the chapel was crowded to excess,” while a tea-party at which he spoke the next day was attended by about 500 people. Similarly, the Lakota performers of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show attracted large audiences in 1903, as did Seneca actress and playwright Gowongo Mohawk’s run of her show “Wep-Ton-No-Mah” in 1893 and the group of Indigenous North American entertainers who danced outside of the Guildhall as part of the 350th Mayflower Commemmoration in 1970. To focus on Plymouth solely as the place from which English colonists sailed on their way to Indigenous homelands can, as historian Coll Thrush has argued, result in “a blindness read back onto the past from the present, an inherited silence where history should be.”[2] What if instead we consider Plymouth as Indigenous space? How could a remembering of Indigenous North American presence in Plymouth change understandings of the city and of those Indigenous travelers?

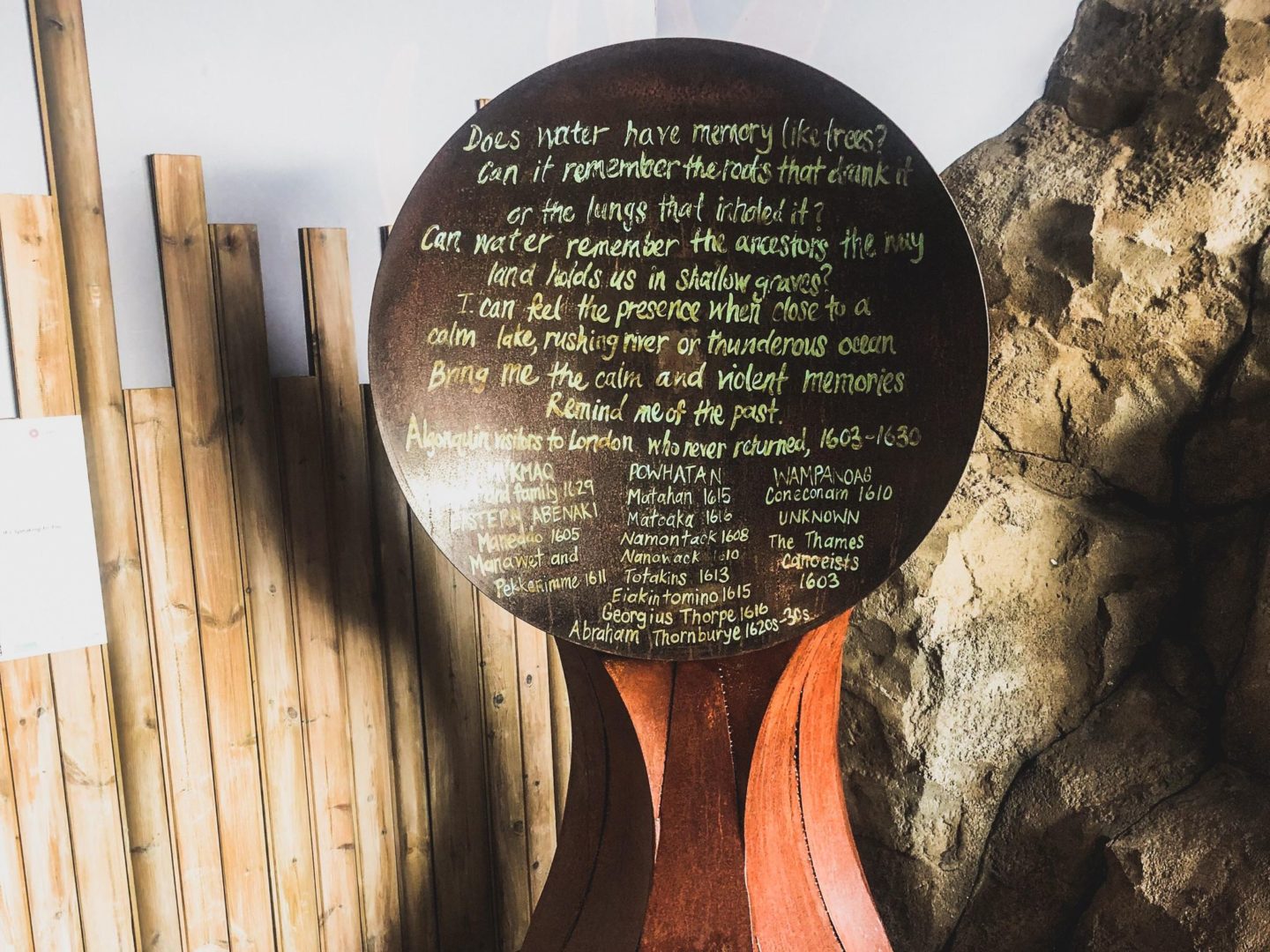

Appropriately, Plymouth retired its official “Spirit of Discovery” tagline in 2013 and rebranded itself as “Britain’s Ocean City.” This ocean has linked Plymouth and Indigenous North America through travel from both directions for over 400 years and this is now commemorated in an installation at the National Marine Aquarium by Chitimacha/ Choctaw artist Sarah Sense. When talking about her piece, Listen to the Atlantic, It’s Speaking to You, she noted that “[b]etween these two places is an ocean carrying stories of people moving between continents” and, as the map demonstrates, Plymouth was and continues to be a key site for those connections and encounters.

NOTES

[1] Brought to England as a captive in 1611, Epenow had ended up under the control of Ferdinando Gorges, the first Governor of Plymouth. He wanted to return to his homeland so he convinced Gorges that there was gold on Martha’s Vineyard (there wasn’t) and Gorges commissioned a voyage there in 1614, during which Epenow escaped. Six years later, he helped lead resistance efforts against the Mayflower colonists. For more information on his story, see Alden Vaughan, Transatlantic Encounters: American Indians in Britain, 1500-1776 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 65-7. You can also listen to Linda Coombs of the Aquinnah Wampanoag tell Epenow’s story in “Captured: 1614, Freedom for Fool’s Gold”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bkYtpsPl5FM

[2] Coll Thrush, Indigenous London: Native Travelers at the Heart of Empire (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016), 14.

[3] Thrush, 14.